A Boon

Louis Paul Boon, a trip to the Netherlands, and a mysterious conversation

Before John O’Brien passed away, when we were talking regularly about the future of Dalkey Archive Press, about what it would/could/should become, he mentioned, on at least three occasions, that he was excited for the future because it was “exactly what we talked about on that bench in Amsterdam.” In fact, I think he told Will Evans this as well (at least twice), and maybe even brought it up at a staff meeting, always alluding to this “crucial” conversation we’d had, never directly revealing its contents.

Which was fine by me, since I have no recollection of this, and “oh, yes, it really is, yep yep” only plays so many times.

John’s remembrance of this single event did always take me back though . . . I might be wrong, but I think this was the first real European editorial trip that I went on with John alone. I had been to Germany thanks to the German Book Office (a wild trip where I met several lifelong friends), and I think John and I had been to London to talk to John Calder (a post—or four—of its own), but Amsterdam was an early part of his new Dalkey strategy: taking advantage of the munificence of the “book offices” across Europe, we would visit their countries, meet with authors, critics, academics, editors, and booksellers to create a hit list of book/authors to publish. Then, we would meet the bureaucrats, explain that, at that moment in publishing, Dalkey was the only game in town doing translations, and that, with proper funding, we would create a series (the Estonian Series, the Austrian Series, the Danish Series), and use CONTEXT, the Review of Contemporary Fiction, and our university connection to really do right by that country’s literature.

The main heart of the argument is a noble one: Rather than behaving like a typical commercial press, only paying attention to the literature of the region if there’s a newly released, buzzy, potential best-seller, we would do a number of titles (you might say a “series”) and try to create a context among English readers for that country’s literary scene through volume, dedication, and smart promotions. This is, in many ways, Nonprofit Publishing 101—mission-driven, not guaranteed of financial success, creating new audiences for highly respected, yet under the radar authors.

This situation can devolve rather fast—see the Best European Fiction anthologies, which I might write about at some point in the future—and become a sort of pay-to-play publishing scheme filled with overstuffed budgets and marketing plans totally divorced from reality—but that initial impulse was pure. And from the point of view of the cultural organizations funding these trips, it must sure have felt good to have a respectable, iconoclastic press enthusiastically paying attention to your literature. Especially in the early 2000s when translations into English were at a nadir.

*

Here’s what I remember from our trip to Amsterdam:

1) We stayed at the Ambassade Hotel because that’s the famous, fancy hotel where the biggest authors came when they visited.

2) We interviewed—and hired—Marleen Reimer who, post-Dalkey times, went on to work as a scout for Maria Campbell and a subsidiary rights manager for HMH.

3) I watched the only episode of The O.C. I’ve ever seen. Paris Hilton was in it. And made a joke about how she was leaving the party early because she was working on her dissertation about Thomas Pynchon.

4) I remember tying this trip together with a visit to Antwerp, where we learned about Flemish fiction and basically signed on, almost sight unseen, Paul Verhaeghen’s Omega Minor, a gigantic, Pychonian book that he translated himself. (More on this in the future.)

5) One night I snuck out to have a drink by myself—John was a 24-hour travel companion, which could be quite exhausting—and when I got back to the hotel, he was smoking a cigar out on a bench nearby, so I ninjaed my way out of a late night conversation.

6) Louis Paul Boon.

*

When Dalkey Archive moved from Fairchild Hall at Illinois State University—a rather nice penthouse office on top of a teacher-training school, where John smoked in his office against all codes and rules, and where students would occasionally make out in the hallway outside our doors—to his basement in Funks Grove, we reshelved his entire library, organizing it by the author’s country of origin, which, to be fair, was both tedious and the most incredible exposure to the history of experimental and international literature.

There are so many stories of books that were reprinted because John wandered through the stacks, picked something up, read a few paragraphs, had a fond memory of the book in question, and said, “hey, we should do this book” to whichever employee was closest. (It was up to that employee to understand this wasn’t a random statement, but an assignment to read the book and report back. The employees who didn’t realize this didn’t last very long.)

That’s sort of how Louis Paul Boon’s Chapel Road got reprinted.

When we first found out we were going to Amsterdam (thanks to the still incredible Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature, which has since shortened it’s rather unwieldy name), I immediately went to the Dutch section of the Dalkey Library and found . . . mostly Harry Mulisch. (Who is interesting, but not that interesting.) But also, this strange unattractively bound book from Twayne Publishers, Inc. called Chapel Road, with one of the coolest openings ever:

Chapel Road which is the book about the childhood of ondine, who was born in the year 1800-and-something . . . who fell in love with mr achilles derenancourt, director of the spinning mill ‘the filature’, but who will at the end of the book marry poor oscarke . . . about her brother valeer-traleer, with his monstrous head wobbling through life this way and that . . . and about mr brys who was one of the first socialists without knowing it . . . about her father, vapeur, who wanted to save the world with his godless machine, and about all the things which I can’t quite recall now, but which try to draw a rough sketch of the laborious RISE OF SOCIALISM, and of the decline of the bourgeoisie which got knocked down by two world wars and collapsed. But between and besides this it is also a book set in a much later time, in our own time of today: whereas ondineke lived in the year 1800-and-something, msieu colson of the ministry, johan janssens the journalist, tippetotje the painter, mr pots and professor spothuyzen—and you yourself, boon—live today, in search of the values which really count, in search of something which will check the DECLINE OF SOCIALISM. But . . . heaven help us if it isn’t going to be more than that: it is a pool, a sea, a chaos: it is the book of all that can be heard and seen in chapel road, from the year 1800-and-something until today.

This one paragraph was all it took to hook me, and to eventually hook John, thus launching Dalkey’s “Netherlandic Literature Series” (which is what we printed on the back of the book, and ugh?) with the first volume of Boon’s masterpiece.

*

It must have been so disorienting to the people at the Dutch Foundation for Literature to have a young American show up in their country, poorly dressed (still haven’t figured that one out twenty years later) and desperately seeking information about an author whose name he mispronounced every single time (it doesn’t rhyme with “moon”). An author who didn’t technically write in Dutch and thus wasn’t eligible for funding from the very organization that flew us over, put us up in a swanky hotel, and was thrilled to finally tell someone in America about all the new, living, exciting Dutch authors worthy of discovery. Instead, there I was asking—over and over—about an author who passed away in 1979, was critically respected but maybe not that well-read, and had a reputation for being a bit of a porn connoisseur. (This is pretty much shorthand for the typical Dalkey author, I suppose.)

*

I hate doing this, but let’s take a second to not appreciate this cover. I would give anything to slide this into the forthcoming Dalkey Essentials series with a new design and an ebook version (and as part of the Belgian Literature Series) . . . Just need to sell out this edition first, if you catch my drift . . .

One of the quirks of the Dalkey catalog is that, to date, Dalkey hasn’t published any books translated from Dutch authors—only Belgian ones. Toussaint, Robberechts, Boon, François Emmanuel, are all Belgian born, and although some write in French, and others in Flemish, I don’t know if any of these publications were supported by the Dutch Foundation for Literature, the organization that set this all in motion. In fact, although the Dalkey website has a catalog page for authors from the Netherlands, that page is completely blank.

Another thing I remember: Taking the train to Antwerp, which meant passing through the red light district with John at like 6 a.m. with myriad prostitutes lightly dancing in their windows and me feeling deeply uncomfortable. That and the fact that Antwerp was cold, overcast, rather depressing. But filled with interesting sounding authors, including Tom Lanoye (now published by World Editions), and Paul Oster (took at least 10 minutes to realize we weren’t talking about Paul Auster who is decidedly not from Belgium). There was even a Louis Paul Boon museum exhibit! Which is where, I think I remember, we found out about Summer in Termuren, the untranslated sequel to Chapel Road.

*

Rather than try and explain Boon’s uniqueness and style based on my shaky memories, let’s turn to Annie van den Oever’s Life Itself: Louis Paul Boon as Innovator of the Novel, a Scholarly Series title that’s definitely worth checking out.

What follows is a long quote about that same passage quoted above, the opening paragraph of Chapel Road:

This sentence, 132 words in the original, is exceptionally long; the average sentence length of the average novelist is no more than twenty to forty words. [. . .]

The structure of this sentence is unusual not only in terms of its length and clumsiness, but also its “primitiveness”: “Chapel Road which is the book about . . . about . . . and about . . . about . . . and about . . .” The primitive element here is the simple coordination of roughly identical subordinate clauses through the repetition of who, who, and but who.

The opening passage immediately shows a curious discrepancy between Boon’s awkward sentences, which rank very low in terms of literary style, and the lofty literary aspirations, expressed in the opening pages, of the narrator Boontje—and for that matter, of the writer himself, who really did aspire to write the masterpiece that many of his later readers perceived this book to be.

The novel on which Louis Paul Boon worked for about ten years and with which he sought to demonstrate his mastery contains an opening sentence that seems to have been written in two seconds flat, as if he had given no thought to syntax, word choice, orthography, and punctuation. The sentence does not suggest that Boon quietly rewrote it several times, as writers usually do. Instead, it looks more like a sentence created at the typewriter, one which has spontaneously grown, spread, and become distended. This impression in created by improvisations like “1800-and-something” and “[Chapel Road is the book about] all the things that I can’t quite recall now.”

There’s a lot more that I could quote, but let’s wrap this up with a couple final anecdotes:

We did end up signing on Boon’s Summer in Termuren, which Paul Vincent translated for us, and which I remember spending my evenings—and plane rides—editing while I was on a different editorial trip to Estonia. (Definitely a future newsletter topic.) Clocking in at a mere 489 oversized pages, according to the author:

This is “the novel of the individual in a world of barbarians.” It is the story of Ondine and Oscarke, a young married couple adrift in a Belgian landscape that is darkening under the spread of industry and World War I. Ondine, who “came to serve god and live,” finds that she must “serve the gentlemen” instead. Oscarke, an aspiring sculptor, finds himself unsuccessfully scouring Brussels for work and, when he is finally hired, too tired to make his own art. They grow old and their four children grow up as “technology and mechanization, unemployment, fascism, and war” take over around them. War destroys their attempts to establish a better life, which they seek continually and against all odds. And the chapters about these characters, some of whom first appeared in Chapel Road, alternate with chapters about Boon himself, who describes the impossibility of modern life and the destruction of war. As this wide-ranging novel progresses, the author's struggles—both with writing and with his own life—come more and more to resemble those of his characters.

These books really should be sold as a special set . . .

(Note: I wasn’t around when Boon’s My Little War came out, but it was always referred to as one of his best books, and is a series of chronicles about life during WWII and the German occupation of Belgium. And Dalkey does still have this in print as well.)

*

And now, the actual inciting incident for this post.

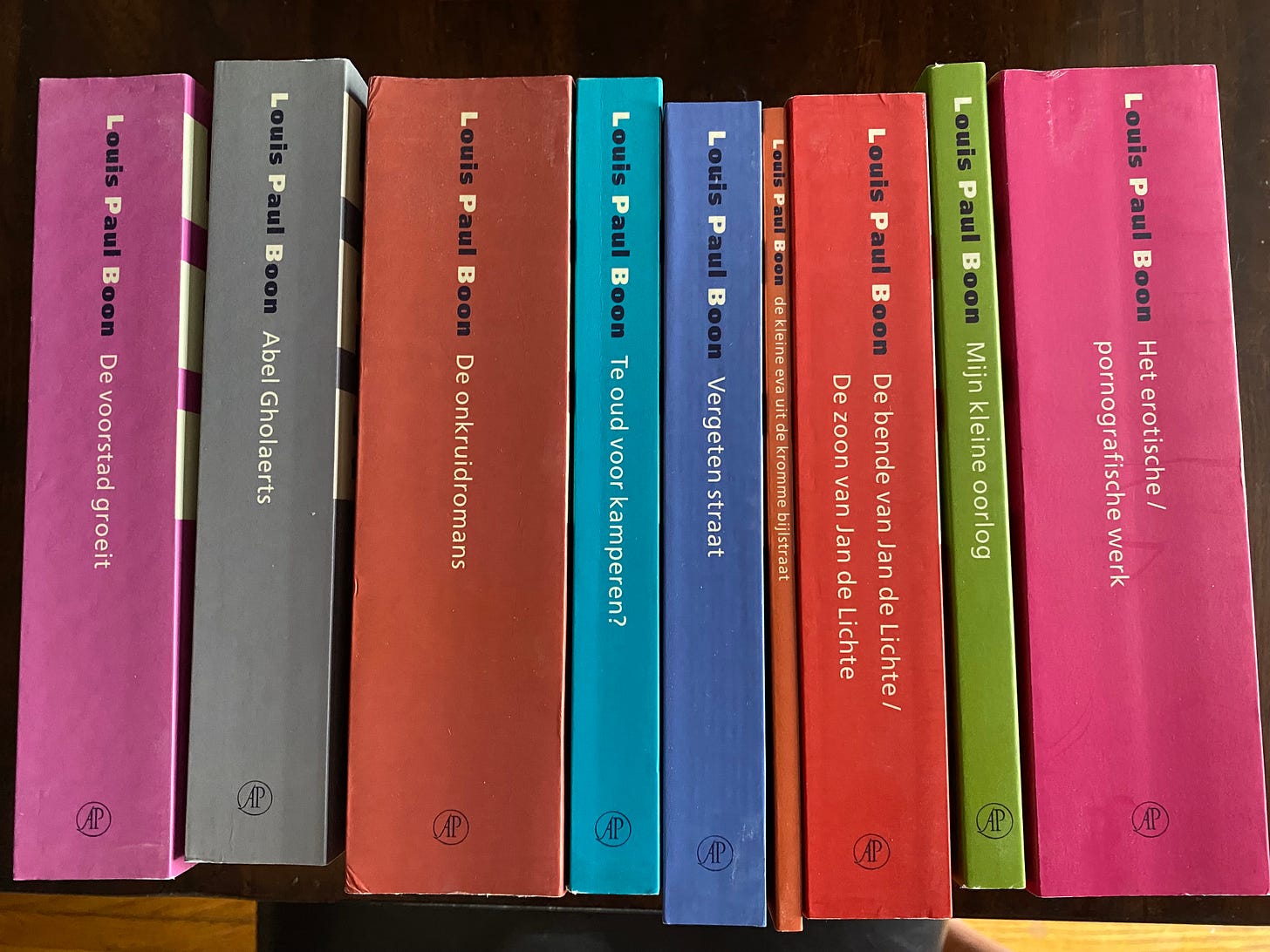

When Will Evans and I were in Normal, IL, going through the Dalkey warehouse, we found this box, which had been shipped over from the University of Illinois, possibly opened up at some point, but containing the complete works of Louis Paul Boon.

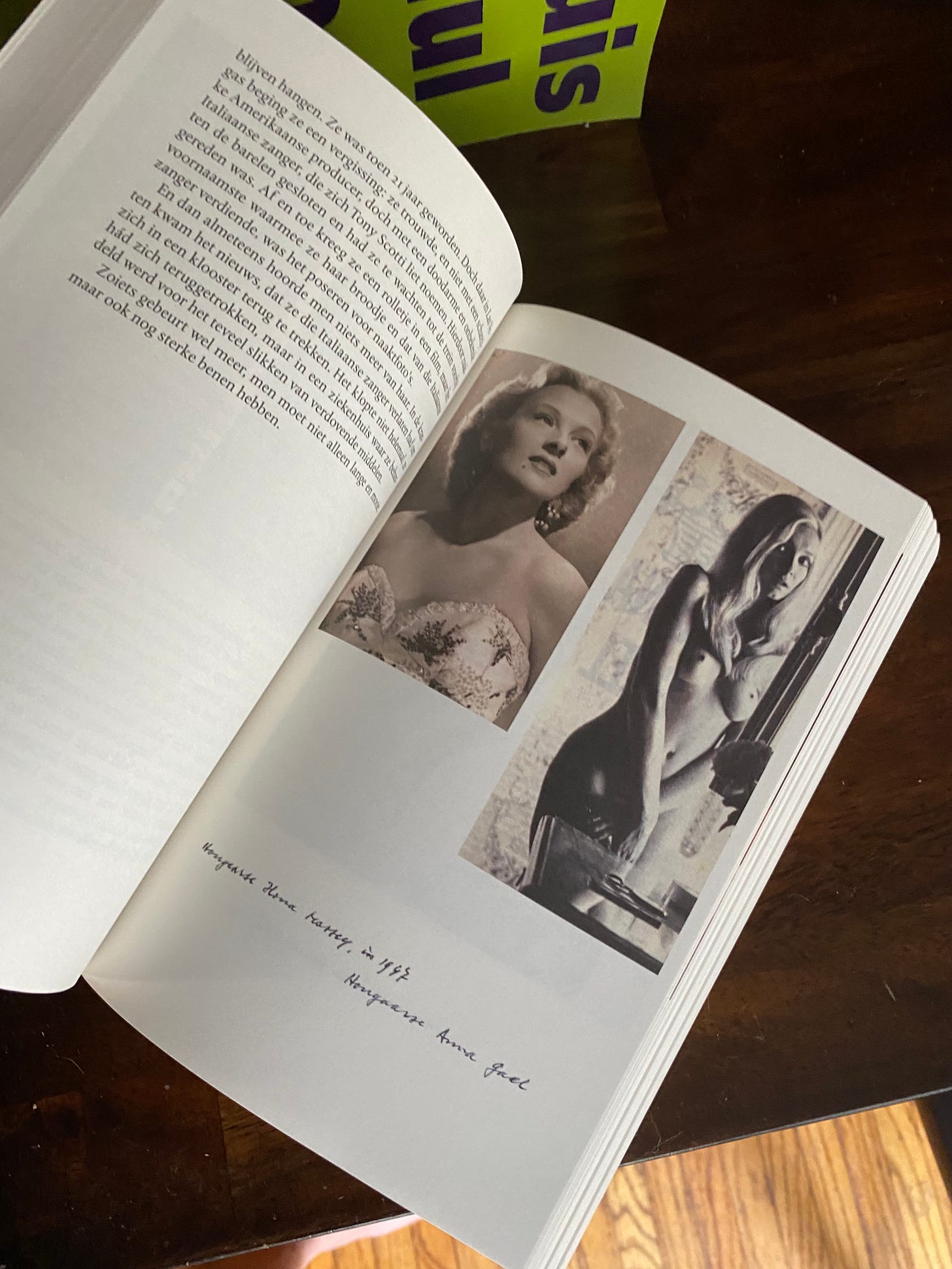

Included in this collection is Het erotische/pornografische werk, which the bookseller at the American Book Center in Amsterdam first told us about. Apparently, or at least as I remember it, Boon collected tons of dirty pictures, which were discovered after he died with notes and writing across the back of the photos:

This is obviously a never-to-be-published Boon book (the image rights alone would be a NIGHTMARE), but hopefully there are a few more Boon gems to uncover. Perhaps that’s what John and I talked about on the bench next to the canal, but probably not. Much more likely that was about the way in which Dalkey could grow into a large, international publishing house, bringing the Boons of the world to light while doing and thinking about publishing in ways that no one else was really attempting at that time.

Or we talked about Paris Hilton and The O.C. Although John and I, to be honest, were much bigger devotees of the Melissa Joan Hart iteration of Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

"bringing the Boons of the world to light". Love this.

I would happily read a book with anecdotes about John O’Brien. Hell, a whole shelf of books.