Forty Years of Dalkey Archive (Part II of V)

Covering 1984–1993

As mentioned in the overview post from last week, between now and the end of the year, I intend to highlight one book per year from the Dalkey Archive catalog. Forty books for forty years.

Before getting started, I want to note that these aren’t necessarily the best-selling books from the year, nor the most famous, nor necessarily the “best.” A lot are personal favorites, but some might mark a moment, or have some other interesting story to go along with them. With over 960 titles to choose from, a ton of books and authors are going to be left off . . . which is why I’m wasting too many words emphasizing that this isn’t a “best of” list or anything of the sort.

However, if you read along, I’m sure you’re going to find a number of titles that you’ll want to add to your library and/or to read list. Be it a featured title or one of the “other notable titles from XXXX” (which are limited to three per year so I can keep my sanity). This is all for entertainment and to demonstrate the breadth and depth of the Dalkey Archive catalog—so enjoy!

Finally, any and all stats to come are from my personal records, and I am incredibly fallible. If I goof, please let me know so that I can update my database and whatnot.

With all that preamble out of the way, let’s get to it.

1984: Splendide-Hôtel by Gilbert Sorrentino, afterword by Robert Creeley

How can you not start this off with the first book Dalkey Archive ever published? It’s hard to argue against Sorrentino’s influence on the press’s aesthetic—especially in these early years when John and Gil were still very close. The first issue of the Review of Contemporary Fiction is dedicated to Sorrentino; the first book is a reprint of this classic that originally came out from New Directions in 1973.

This also kicks off a subtle obsession of John’s: Books about or featuring hotels. Granted, this meditation on language and poetics isn’t about a real hotel in a neo-realistic sense, but you’d be surprised by just how many hotel-related books are in the Dalkey list and how often John talked about and was drawn to these. So it’s a nice coincidence.

Total Titles Published in 1984: 4

Countries Represented: 2

Translations Published: 0

Other Notable Titles from 1984: Season at Coole by Michael Stephens, Cadenza by Ralph Cusack, Wall to Wall by Douglas Woolf

1985: Some Instructions to My Wife: Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage, and to My Son and Daughter Concerning the Conduct of Their Childhood by Stanley Crawford

This book is a perfect exemplar of the tongue-in-cheek, dark humor of many a Dalkey Archive title—it’s rude, uncouth, unacceptable, and requires the reader to not take it at face value. Which may well run counter to today’s sensibilities, given its surface level misogyny and patriarchal way of ordering the world.

Although the way Crawford’s narrator orders the world via these instructions, compartmentalizing every aspect of the household into its “proper place”—there are chapters on “Putting Things Away,” “Daily Appearances,” “Clothes,” “Windows,” “Weeds,” “Electricity,” and “The Goats,” among many others—is an interesting nod to the Oulipo and books like Mathews’s The Journalist in which all attempts to force this sort of “logical” system on the world leads to a leakage of chaos.

Total Titles Published in 1985: 4

Countries Represented: 3

Translations Published: 0

Other Notable Titles from 1985: Accident and Impossible Object by Nicholas Mosley, Out of Focus by Alf MacLochlainn.

1986: Where Do You Put the Horse?: Essays by Paul Metcalf

To the best of my knowledge, I’ve never seen this book in real life. (Although according to the Woodland Pattern website, they have one on their shelves! Or did, since I just ordered it.) Metcalf—the great-grandson of Herman Melville—was a prolific writer, beloved by many of the greats, whose Collected Works are published by Coffee House (along with a standalone edition of Genoa) was essential to the founding of the Review of Contemporary Fiction. From John’s self-conducted interview:

One afternoon, Paul Metcalf was visiting me during one of his layovers at O’Hare airport, a habit he had gotten into in his trips across America. This particular afternoon, sometime in the spring of 1980, we were complaining about the state of literary criticism and said that someone had to start a magazine that would cover the writers who were being excluded. I decided that afternoon that I would be the one.

Where Do You Put the Horse? is also notable for 1) being the first collection of essays published by Dalkey Archive, and 2) being the only book to come out this year. (It’s possible a special limited edition of Alexander Theroux’s Lollipop Trollops and Other Poems came out this year, but I’m not 1000% sure, so I’m just going to footnote it for now.)

Total Titles Published in 1986: 1

Countries Represented: 1

Translations Published: 0

Other Notable Titles from 1986: N/A

1987: The First Book of Grabinoulor by Pierre Albert-Birot, translated from the French by Barbara Wright

I’ve been “researching” a post on Barbara Wright for months now, given her incredible influence on Dalkey Archive’s French list, so I feel like I have to note the first title she did with the press. [Note: Her translation of Queneau’s Pierrot Mon Ami was also published by Dalkey Archive in 1987, but since Grabinolour came out from Atlas Press in 1986, I’m calling this the first of her translations.] Albert-Birot’s First Book of Grabinolour (of which I don’t believe there was a “second,” but if I’m wrong, hit me up) is influenced by Rabelais, Apollinaire, and, in spirit at least, the Futurists, Cubists, and to some degree, the Surrealists. (There’s something so engrossing about all the French movements and the ways in which the best French writers of the time approach and evade the influence of these groups. I am not qualified to speak to any of this in detail, but I sure do love reading about it.) It’s a very “concrete poetry” sort of book that would be a nightmare/artistic opportunity to typeset (we need to re-typeset it) and holds a special place in my heart, since the paperback version was the first book that came out when I started at Dalkey as an “apprentice” in July 2000. Martin Riker was a big fan, which had a huge influence on me.

Also: This cover is noteworthy both for leaving the Gallimard style of the early books behind (which was also true with the Metcalf), and for prominently putting the translator’s name on the front cover. No one had scolded John into doing this; no op-eds had been written.

Total Titles Published in 1987: 8

Countries Represented: 3

Translations Published: 4

Other Notable Titles from 1987: He Who Searches by Luisa Valenzuela & Helen Lane (first female author to be published by Dalkey Archive), Our Share of Time by Yves Navarre & Dominic Di Bernadi, Too Much Flesh and Jabez by Coleman Dowell

1988: Interviews with Latin American Writers by Marie-Lise Gazarian Gautier

Although the official “Scholarly Series” won’t launch for quite some time, this is a definite precursor to that subset of Dalkey Archive titles. Latin American literature is what drew me to translation, so it’s not surprising that this was one of the first Dalkey Archive titles I acquired. (From a used bookstore in Grand Rapids, MI, where I also found a copy of Queneau’s Zazie in the Metro with a handwritten note on the title page condemning its “obscenity.”) And look at that line up! I mean, Allende is whatever, but Cabrera Infante and Fuentes and Onetti and Puig and Sábato and Sarduy and Valenzula. And Luis Rafael Sánchez, a Puerto Rican writer whose Macho Camacho’s Beat deserves to be a Dalkey Archive Essential. In fact, Dalkey Archive published six of the included authors—a pretty solid ratio.

And a couple years later, Gazarian Gautier published a collection of interviews with Spanish writers that included conversations with Camilo José Cela, Ana María Matute, Juan Goytisolo, Rosa Montero, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Julián Ríos, and Juan Benet. This sort of scholarship is always invaluable—and calls to mind John’s own book, Interviews with Black Writers.

Total Titles Published in 1988: 8

Countries Represented: 3

Translations Published: 6

Other Notable Titles from 1988: Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson, Mise-en-Scène by Claude Ollier & Dominic Di Bernadi, 20 Lines a Day by Harry Mathews

1989: Willie Masters' Lonesome Wife by William H. Gass

I’m not going to bother trying to explain this book which, in terms of textual play brings to mind Albert-Birot’s Grabinolour, but uses even more advanced typesetting techniques. See below.

There are any number of reasons to highlight a Gass title—Dalkey Archive has published nine to date, including The Tunnel audiobook, a project I helped bring to fruition and sell into bookstores, and to which a great debt is owed to the Lannan Foundation—but two memories leap to mind: 1) this book was banned in Singapore thanks to the breasts on the cover, and 2) in Normal, IL (where Dalkey Archive was based for most of its existence), there was an electrical/HVAC place named Wm. Masters, Inc. There was no way not to think of this book and its “lonesome wife” every time they came to the office to fix something.

Total Titles Published in 1989: 12

Countries Represented: 3

Translations Published: 3

Other Notable Titles from 1989: Locos by Felipe Alfau, Hortense Is Abducted by Jacques Roubaud & Dominic Di Bernadi, Samuel Beckett’s Wake by Edward Dahlberg

1990: Cleaned Out by Annie Ernaux, translated from the French by Carol Sanders

For what’s it’s worth, Dalkey Archive published future Nobel Prize winner Annie Ernaux in English before anyone else. Before Seven Stories, before Fitzcarraldo. And to adopt John’s grump, his edge, his annoyance at being overlooked for a moment (a vibe that is most definitely part of Dalkey Archive lore): even though Dalkey Archive introduced the American public to Ernaux, they got basically no credit for it. For instance, althoguh Cleaned Out is referenced twice, there’s no mention Dalkey Archive in this Nobel Prize announcement in the New York Times.

Fast forward a few years and the same exact thing happens with Jon Fosse. I personally read the submission for Melancholy from Damion Searls and Grethe Kvernes in 2004/5 and sat in John’s dimly-lit office late one afternoon convincing him—by reading excerpts of the translation sample aloud—to publish this. Unfortunately, I left to found Open Letter just after Melancholy came out in fall 2006, and slightly before John and Jon became close friends—a connection that lead to Dalkey doing six more Fosse books—so I wasn’t there to shepherd all his titles into the hands of eager readers and booksellers.

And yet, despite all the efforts in getting Fosse into English and sticking with him when his books barely sold, not once do the words “Dalkey Archive” appear in all this NY Times coverage of Fosse’s Nobel Prize. Curious. This truly is not hard to research, and yet.

Reminds me of NPR claiming that in this year of our lord 2024 that Norton was gracious enough to finally translate Gospodinov’s Physics of Sorrow into English—a book Open Letter published in 2015. Again, this is readily available info. And makes me suspect everything NPR does.

History matters, folks. And so does good reporting.

Anyway, Annie Ernaux is great, and this book, wrenching.

Total Titles Published in 1990: 15

Countries Represented: 5

Translations Published: 7

Other Notable Titles from 1990: Chromos by Felipe Alfau, Larva by Julian Ríos & Richard Alan Francis & Suzanne Jill Levine, Complete Short Stories by Ronald Firbank

1991: The Great Fire of London by Jacques Roubaud, translated from the French by Dominic Di Bernadi

R.I.P. Jacques Roubaud. Your Hortense novels made me laugh, your Some Thing Black broke my heart into a million pieces and showed me the outline of true love, your compulsion to walk everywhere, all the time endeared me. But “The Project” is what captured my imagination and instilled a love of complex, mathematically driven literature.

It’s incredible to think that Dalkey Archive was the first and (so far) only publisher to do any of the books from this series, which he started writing after the untimely death of his wife, Alix Cléo Roubaud, in 1983. This sequence of seven semi-autobiographical novels that both predate and eclipse Knausgaard in structure and ambition is one of the grandest projects to come out of the Oulipo. It’s monumental and, based on the three volumes that have been translated into English, one of the great works of the twentieth century. It is my life’s goal to see all of these available in a matching set and for us non-French readers to finally see the scope of this project that took from 1989–2008 to complete.

Sticking with the first volume of this series, The Great Fire of London, for a second, this a book that consists of a) a text, b) bifurcations, in which, if you follow a certain symbol, the main story, the main thought, branches, and c) interpolations, that dive deeper. It’s Cortázar’s Hopscotch on crack.

And if you want this whole series to be published in English, write to me. This project needs to be completed and the more people who show support, the more likely it will.

Total Titles Published in 1991: 18

Countries Represented: 6

Translations Published: 8

Other Notable Titles from 1991: Theory of Prose by Viktor Shklovsky & Benjamin Sher, Stranded by Esther Tusquets, Muzzle Thyself by Lauren Fairbanks

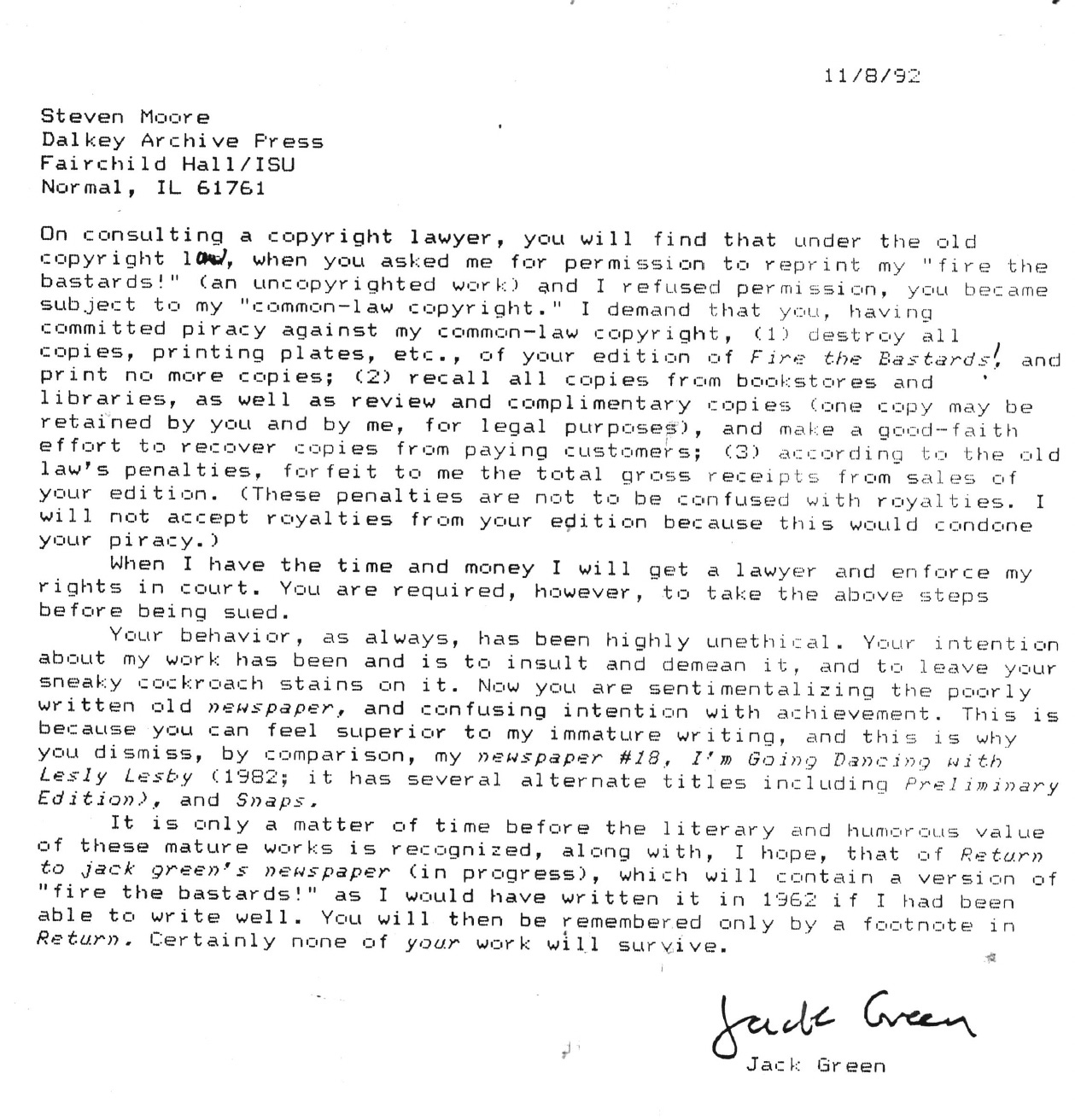

1992: Fire the Bastards! by Jack Green

Jack Green was the original blogger. The one reader who knew more about a truly monumental art work than the people being paid to write about it. And he caught them in their bullshit. Basically, Green tracked all the reviews of Gaddis’s The Recognitions—to which he was an early-adopter in terms of recognizing it as a masterpiece—and quickly cottoned on to the fact that the reviewers who wrote about Gaddis’s novel were predominantly frauds.

So he collated excerpts from their garbage reviews, added some incendiary interstitial bits, printed it as a pamphlet/zine, and handed it out on the streets of New York.

Ironically, by exposing the deep hypocrisy and laziness of book criticism revolving around William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, Fire the Bastards! proves the point that real literary criticism could exist. Not that any of the reviewers cited in the book—all of whom crib jacket copy as if it provided genuine insight and copy each other mercilessly, replicating factual errors because they’re too lazy to actually read the book or do any research (*cough* see above *cough*)—are good examples of the merits of this enterprise, but the fact someone cared enough to put together and produce a cogent argument against this particular grift is astounding. And means something.

I love this book.

I love its anger.

And I love the fact that, three decade ago, Dalkey Archive published it sans contract. (This was back when publishing was a proper industry filled with con-men and half-truthers and not MBA quants.)

Total Titles Published in 1992: 24

Countries Represented: 5

Translations Published: 8

Other Notable Titles from 1992: Night at the Movies by Robert Coover, Going to Patchogue by Thomas McGonigle, Collected Writings by Olive Moore

1993: Annihilation by Piotr Szewc, translated from the Polish by Ewa Hryniewiz-Yarbrough

Compared to the bombast of Fire the Bastards!, Annihilation is a “quiet” book. A book about life in a small Polish town that we as readers know, but the characters do not, is about to be demolished by Nazis.

Here’s a lengthy excerpt from Martin Riker’s piece about it that appears in Context #19, available in full, for free, here.

To all appearances, Annihilation is a very simple book, quiet and charming. Its most immediately remarkable aspect—the thing the reader notices right away—is that it is composed almost entirely of details. Set in 1934, it recreates, from morning to night, a single July day in a town modeled on the eastern Polish city of Zamosc, which prior to World War II was a center of Jewish culture. In 1942, Zamosc was declared the “First Resettlement Area” by the Germans, after which “ethnic cleansing” began and tens of thousands of the city’s inhabitants were either killed or shipped to extermination camps. What is surprising about Annihilation is that, with the exception of the title and some indirect foreshadowing, none of this destruction is found in its pages. The text itself, its surface, maintains a tone of tenderness and unhurried observation, concerned not with the future but only with its present ambition to “chronicle the events in the Book of the Day,” of which everyone and everything in the town isa part. Thus the novel’s ambition is not to create a narrative of events and causes (i.e., a history) but rather to perform a massive act of attention, to force the reader, through unabashed insistence on detail, to inhabit a present that is otherwise irretrievably past.

We might ask how a novel composed entirely of details, a novel with almost no plot, nonetheless maintains momentum, creates literary tension, and manages not only to avoid being boring, but to carry considerable emotional weight. In the case of Annihilation, the answer is not by being aggressively subversive: the fictional world Szewc offers is, on the surface at least, familiar and inviting, and more importantly, its readerly satisfactions are immediately available in a way usually associated with realist narrative. Szewc manages to provide this satisfaction by replacing standard devices of narrative (for example, plot)with what we might call devices of attention, which create and satisfy expectations of attention just as narrative works create and satisfy expectations of action. Acts of perception replace narrative action; details, in a sense, stand in for verbs.

This process starts from the first word of the book, which is an unusual use of the pronoun “we”:

“We are on Listopadowa, the second street crossing Lwowska. In one of the tiny backyards close to the intersection, Mr.Hershe Baum is standing near the house and feeding pigeons perched on his arm. Here they are called Persianbutterflies. Isn’t it a beautiful name? In all likelihood they were brought from Persia. But is that certain? We won’t beable to verify it. Data, documents, and credible explanations are unavailable.”

This “we” proves extraordinarily slippery, involving the reader right away in a high level of intimacy—“we” share a single perspective throughout the book—but existing separately as well, a kind of tour guide of the imagination. The narrator occasionally makes reference to the future, to how “we” will look back upon this day, this town, but even these gestures are speculative, looking forward from the particular space and occasion of this past in which “we” exist as a surrogate character, a physical-yet-invisible presence, knowledgeable about the town’s inhabitants but unable to affect daily events. “We” can see into characters’ thoughts but cannot verify most factual information, and are vaguely aware of the future but not explicitly concerned with it. A typical line in Annihilation—“As our eyes follow the cart, the sun, reflected off a window that someone is opening, blinds us”—reinforces the reader’s position inside this shared perspective, which, though physically impossible, is nonetheless extraordinarily intimate, two consciousnesses sharing a single pair of eyes.

Total Titles Published in 1993: 18

Countries Represented: 4

Translations Published: 3

Other Notable Titles from 1993: AVA by Carole Maso, The Dalkey Archive by Flann O’Brien, Women and Men by Joseph McElroy

Stay tuned! This is just the beginning of our journey . . . there’s so much more to come . . .

Yes please on the Jacques Roubaud!!! Sounds right down my alley. I did the KOK from Archipelago Books and it was a LOT. But I love big books and helped with the copy-editing of the Miss MacIntosh, My Darling and am seven chapters in on a complete read....

Another yes on the Roubaud! Especially a reprint of The Great Fire of London!!