On "Chapel Road" Being a Dalkey "Essential"

My introduction to the forthcoming Dalkey Archive Essential edition of Louis Paul Boon's "Chapel Road."

What follows is my introduction to the forthcoming Essentials edition of Chapel Road by Louis Paul Boon, which, if all goes according to plan, will be joined by its sequel, Summer in Termuren (currently available in the original edition).

Given that this is an introduction, there’s truly no other set-up necessary . . . But I will let you know that an excerpt of Boon’s My Little War will run this Wednesday.

On “Chapel Road” Being a Dalkey “Essential”

Debating what makes a Dalkey book a Dalkey Book is a philosophical exercise that’s two parts silly and one part a pathway to an academic career. So, three parts silly.

John would often say, “A Dalkey Book is a book that Dalkey publishes,” sometimes replacing that second “Dalkey” with an “I,” a truism that’s nearly impossible to argue with—especially since there are a thousand titles (and only a few people—if any—who have read them all) to support your argument as to what constitutes the quintessential Dalkey book.

But there’s something useful to categorizing Dalkey Archive’s backlist and pulling out and observing the tricks and techniques, the approaches that rhizomatically connect great works of literature across time and space, eventually giving rise, when seen from above, to an implied literary tradition both invented and fostered by the press’s list. There are many routes by which to traverse any finite and constructed tradition such as Dalkey’s, detours and digressions to distract, trails veering off to books of all kinds—some fun, some extremely serious, some duds, some life-changing. In my opinion, at least, one firm path running through the forest of Dalkey backlist leads to work exemplifying a heightened awareness of the influence of form. A sort of impossible object that can observe itself coming into existence. For these works, the old adage holds true: it’s not the story itself that makes a classic, but the way that story is told. Bonus points to Dalkey Archive’s best books, which accomplish this with complexity and self-awareness.

As a guideline on how to write an introduction for a classic, underappreciated work, I can call to mind several others in which the Writer, writing about the book being reprinted, a book that usually has fallen out of favor, but had, back in a sepia-toned past, a great impact on the Introduction Writer’s formative years, a book the new youth should also be formed by, and as such, in one of those sort of very good, solid, dependable introductions, this Introduction Writer will recount the first time they encountered the book, lingering on its feel or smell, the particular bookstore in which they first uncovered this gem; the professor who recommended this book in an offhand way, oblivious to the impact it would have on the Introduction Writer’s life; the Introduction Writer’s romantic entanglements at the time, an ex-girlfriend, the one who got away after gifting the book. An origin story that rightly balances serendipity and fate in a way that’s both nostalgic and contemporary.

So here’s my version: I found the Twayne Publishers 1972 edition of Chapel Road by Louis Paul Boon—the first ever English translation of the book you have in your hands, reader (another sort of statement that a lot introductions include, possibly because they want to make sure you notice the beautiful new cover of the product you purchased)—right outside my office door in Dalkey’s headquarters in Funks Grove, Illinois on a shelf marked: “Netherlands.”

This was the same day that John and I found out the Dutch Foundation for Literature was sponsoring us to spend a week in Amsterdam learning about the literary scene: authors old and new, translated and not, with the goal of producing a Dutch Literature Series. At the time, I knew of Harry Mulisch (The Assault is tight, brilliant) thanks to my bookselling experiences, but, like most Americans in their mid-twenties, nothing else. Which is why I turned to John’s extensive library and found . . . a Flemish masterpiece.

Now I’m not going to pretend that I understood the nuanced difference between Flemish and Dutch at the time, but I did know that, from the opening paragraph alone, Dalkey Archive was going to reissue this book:

Chapel Road which is the book about the childhood of ondine, who was born in the year 1800-and-something . . . who fell in love with mr achilles derenancourt, director of the spinning mill ‘the filature’, but who will at the end of the book marry poor oscarke . . . about her brother valeer-traleer, with his monstrous head wobbling through life this way and that . . . and about mr brys who was one of the first socialists without knowing it . . . about her father, vapeur, who wanted to save the world with his godless machine, and about all the things which I can’t quite recall now, but which try to draw a rough sketch of the laborious RISE OF SOCIALISM, and of the decline of the bourgeoisie which got knocked down by two world wars and collapsed. But between and besides this it is also a book set in a much later time, in our own time of today: whereas ondineke lived in the year 1800-and-something, msieu colson of the ministry, johan janssens the journalist, tippetotje the painter, mr pots and professor spothuyzen—and you yourself, boon—live today, in search of the values which really count, in search of something which will check the DECLINE OF SOCIALISM. But . . . heaven help us if it isn’t going to be more than that: it is a pool, a sea, a chaos: it is the book of all that can be heard and seen in chapel road, from the year 1800-and-something until today.

I don’t know what makes a Dalkey Novel a Dalkey novel, but this sure is an impressive way to start one.

A common trope among Dalkey’s most beloved books is a character within the book writing a book. Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds is a novel about a young man writing a novel within which a novel is being written and the characters have to write their way out. It’s a form Gilbert Sorrentino plays with in Mulligan Stew, his novel of poorly written chapters that pays homage to At Swim-Two-Birds while innovating on the trick. Most of Dumitru Tsepeneag’s intricately structured books are about writing the struggles of writing a novel. The Making of Americans is incredibly aware of itself as an attempt to write a novel. Coover’s A Night at the Movies. All of Barth. The number of examples in the back catalogue are too many to list here. Especially when you include not just the books with the narrator explicitly writing a book inside the book, but books that puzzle themselves out as they go.

This sort of play, in which a novel is aware of its construction in progress, dates back to the Greeks, runs through Joyce and Tristram Shandy (the book I’m going to likely fail to convince you is most closely aligned with Chapel Road) and the work of all the authors named above, is, to a lot of people who fall into the orbit of Dalkey Archive’s backlist, incredibly fun and rewarding to encounter in all its iterations from across the globe.

I’m cheating in that last little riff. In an attempt to make you a Louis Paul Boon fan, I gave you my backstory of picking that book up off the shelf and finding the sublime in the opening paragraph, then immediately tied this to the Grand Tradition of Innovative Literature and subtly implied that if you’re hip, if you’re a literary reader, a “Dalkey Reader,” you’ll love this sort of meta shit. Which isn’t a given: most books written in this self-aware style are boring flops. Failed experiments. It’s a risk trying to write an intro in the vein of the book’s own style, especially when choosing One Big Idea affirming Chapel Road’s space in the Dalkey Essential Series—a truly self-indulgent gesture, given that I came up with the idea of the Essentials and decide what gets included. Especially since there are other, equally valid Big Ideas on which to frame this same argument, such as how the best Dalkey Books are voice driven, or how “Big & European” is a defining feature of Dalkey’s backlist.

But maybe, just maybe, that flaw is what points to what works so well in the titles of this sort that Dalkey publishes: they’re self-aware of their own shortcomings.

But before we get to that, first, a bit about Chapel Road.

Even though Flemish isn’t Dutch, and two different governmental organizations fund the two literary traditions, John and I were able to visit Antwerp (dreary, gray) on our Amsterdam trip. We visited the Louis Paul Boon Center, where we learned about the author’s porn habit and the untranslated sequel to Chapel Road entitled Summer in Termuren, which we immediately acquired and had translated. John also loved that opening paragraph, and our joint enthusiasm made Louis Paul Boon a Dalkey Author since he was published by Dalkey.

Also on this trip we discovered Paul Verhaegen’s Omega Minor, an incredible Pynchonian novel set in the 1990s but about World War II and loaded with all the requisite Nazis, theoretical physics, and the self-awareness to qualify as a “Dalkey Book” of the formally innovative variety.

Also, another Flemish book.

Dalkey has yet to publish a Dutch book.

Chapel Road is exactly the book it says it is. In it, l.p. boon is writing a book called “Chapel Road” about ondine, a young woman growing up in the shifting times when industrialists and the wealthy ruled everything, and the little man had to organize for their rights. But that book is constantly interrupted by all of boon’s friends who come to check in on him, shoot the shit, criticize his novel, gossip, and complain about the tide shifting away from socially-conscious policies and toward more capitalist-driven ones.

I should note here that my lack of capital letters in the previous paragraph is intentional and mirrors the book itself. Throughout Chapel Road, Boon’s eschews most capitalization and his punctuation is haphazard. In proofing this newly typeset version—the one in your hands: this intro is aware of being an intro—there were a number of instances where I’m not sure if a particular quirk was intentional or if someone at Twayne just dropped the ball. I left those in, since they haven’t bothered anyone in the fifty-plus years the book has been in print, and, on a good night, I can read meaning in the extra space between “ha” and “!” as a textual way of playing up the joy in the exclamation—“ha!” Instead of just “ha!” it comes off as two beats, a joy that bounces over the little blank space to be both a “ha” and a “!”

So we’ve got boon’s book, the “Chapel Road” inside Chapel Road, and the interruptions, which are equally important and account for about the same number of pages in this hefty novel. And then we have the third part: johan janssens’s newspaper columns, mostly about Reynard the Fox and Isengrum the Wolf. He retells these fables to critique the current situation, but even outside of that context—don’t worry, the history isn’t daunting in this book—these are entertaining interludes. Which is key, since although Boon (and boon) writes with the lightness that Calvino describes in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium, there’s some heavy shit depicted in this novel—especially in depicting ondine’s social situation.

One scene in particular—no spoilers—deserves a totally different introduction that examines this book from a more feminist perspective. Or at least one more historically grounded and coming at the text from a sociological vein. A bit of a teaser for you.

But that’s the sort of analysis you get in the next reissue of Chapel Road; in this one you just get structure.

And we’ll end with that structure, and the awareness of it on both Boon and boon’s part. But first, I have to pick up that earlier thread about the best of these books being aware of themselves and their shortcomings. That’s prevalent throughout Chapel Road, both from the shit-shooting friends who tell boon to write different, or with more detail, or why doesn’t he do this?, and from boon himself, who includes chapters he immediately wants to abandon, playing out his initial statement that this book’s shape, its structure, is “a pool, a sea, a chaos.”

As I was saying, this book starts by stating what it’s going to be and then tries to get its engine going through a series of fits and starts. The first half-dozen pages are l.p. boon telling us what the novel is that he’s going to be writing, until he finally gets into it with a handful of sections that lay out the situation in which ondine finds herself and of which, when we, the readers, alongside l.p. boon’s friends, who are also readers (and/or listeners), finish that depiction of what he’s going to do, we get this:

As far as I can make out, says the music master, all the people you write about are abnormal: you pick hundreds of little facts from normal life but you mix them unrecognizably into a teeming mass and then you push this mass on to some non-existent plane.

Which, in an academic setting, is one of those moments in which a “book teaches you how to read it.” Expect interruption and interrogation of what you just read. The text isn’t sacred; it’s a text that’s observing how it tries to say something it believes is important.

And then we get to page 33 and johan janssens makes a very metatextual gesture by physically pointing to a printed (maybe) critique of a book we’re watching try to come into existence:

But johan janssensn interrupts you now by asking whether he wasn’t talking about something altogether different, about the drama reaching its climax? Haha, and with a great gesture he reaches into his inside pocket and conjures out of it a weekly journal . . . the illustrated art review . . . and moving his index finger down the columns he says: wouldn’t it be better to torment yourself with this here: although the writer of ondineke of termuren has remarkable talent, he lacks a sense of drama and he speaks flemish in such a way that his pathos seems nothing but feverish ranting . . . Then he folds the journal up and says: well, here you are, letting your heroine think and thinking yourself whether she’s thinking about the right thing and there they’re saying not only that your pathos is feverish ranting, but also that you’ve got no sense of drama . . .

But as I was saying, it’s not just boon’s friends who interrupt his flow and invade it with their ideas; he’s just as prone to do it to himself by imagining a chapter that will never be written:

This is the end of the chapter ‘middle class recipes’, but something seems to be missing: it should really have been written quite differently, more stress should have been laid on the incomprehensible desire to keep up appearances against all better knowledge. But if this had been stressed more, then the title should have been altered too . . . for instance: the proletariat of the middle class . . . yes, that would have been something.

All of this is fun, a special mix of criticism of art and culture and entertainment, and I hope by now you’re on board enough to dip your toe, cautiously, into this book that I assume you’ve already bought—not for this introduction, dear god not for this, but because of that flashy new cover I keep drawing your attention to, and the cultural weight it has by being an “Essential” Dalkey book, a concept both nascent and eternal, one that hopefully this introduction helps clarify, a bit, right now in fact, as we bring in the drawings.

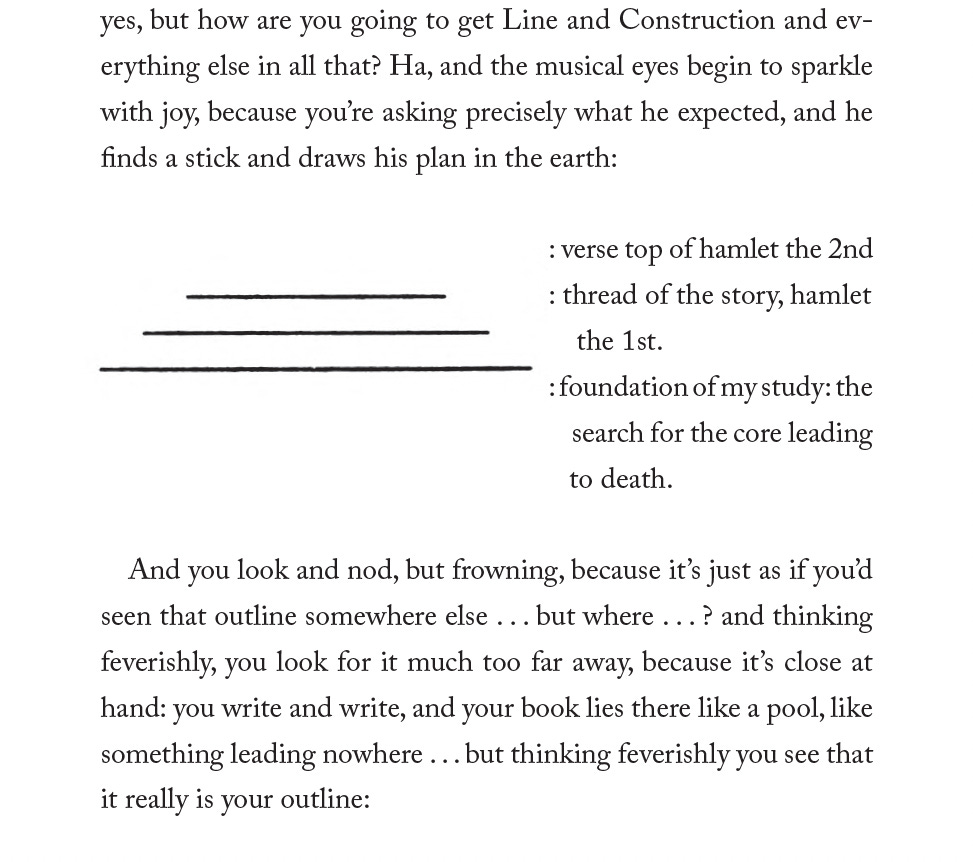

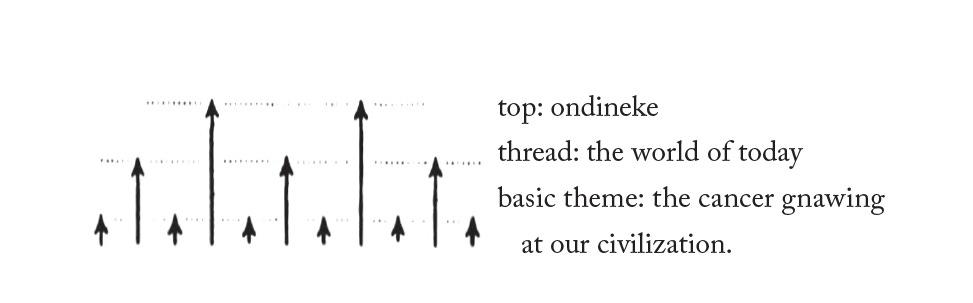

Pulling from the meta-inventiveness of Tristram Shandy, these drawings point to the formation of the book and its awareness of how it is being put together. Boon is offering a roadmap to how he’s going to construct this book and providing a pattern that he’s definitely not going to follow in a strict way. But he’s letting you in. He’s letting you observe how a narrative—about a young woman striving, about societies inequities, about life itself—only gains shape as it is built. As the chaos becomes a pool becomes a sea.

There are few readerly encounters more exciting than witnessing someone brilliant, who, in what feels like real time, builds out a multi-leveled

world.

Before I get out of here I want to recommend, wholeheartedly, Annie van den Oever’s study of Boon, Life Itself: Louis Paul Boon as Innovator of the Novel for a much more nuanced evaluation of his work, along with the biographical information that fl eshes out of one of Flanders’s greatest writers.

I also want to assure you that the other books of Boon’s that Dalkey has published—Summer in Termuren and My Little War—are as “Essential” as Chapel Road. Either one of those could be the inspiration for this introduction, but sometimes it’s that first experience, that first glimpse into a writer’s world that grabs you, transforms your reading life, converts you into a lifelong fan, and leaves you eager to sing the praises of this singular work to anyone who will listen:

Chapel Road which is the book about the childhood of ondine, who was born in the year 1800-and-something . . . who fell in love with mr achilles derenancourt, director of the spinning mill ‘the filature’, but who will at the end of the book marry poor oscarke . . .

This introduction appears in the forthcoming (October 2025) Dalkey Archive Essentials edition of Chapel Road by Louis Paul Boon, which is available for preorder from Bookshop.org and better bookstores everywhere.