Reading Kathy Acker

Approaching one of the most provocative authors of our time.

As I continue working on a bunch of posts about Dalkey Archive’s French literature series, Barbara Wright, and Warren Motte, I thought I would take a minute to share the following piece from issue 9 of Context: “Reading Kathy Acker” by Kathleen Wheeler.

The main reason I want to run this, as a huge Kathy Acker fan, is to draw your attention to the Two Month Review podcast where, last month, we did four episodes on Acker’s Empire of the Senseless (episodes 1, 2, 3, 4), which turned out to be one of our strongest seasons due in large part to the fact that co-host Kaija Straumanis was definitely not a fan of the book. (Also worth noting that we did a season that covered all five of Ann Quin’s books, someone Wheeler references a number of times below. You can find the intro episode here.)

If you already listened to those episodes, below you’ll find someone much much smarter than me articulating what makes Acker’s work so interesting; if you haven’t heard them, hopefully Wheeler’s piece will pique your interest and you’ll check out the podcast. (Also: our next season starts Thursday and is about Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. You can subscribe via Substack, YouTube, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.)

In terms of setting the scene, based on Wheeler’s reference to when Acker died, I believe this piece came out in 2001 (or early 2002), in an issue of Context that contains “readings” of Danilo Kiš, Raymond Queneau, and Stanley Elkin’s The Franchiser (specifically, this is the intro by William H. Gass, which can be found in the forthcoming Essentials edition of The Franchiser alongside Adam Levin’s new introduction). It also contained a “Letter from Russia,” which includes references to Sorokin, Pelevin, and Akunin; and Curtis White’s essay, “The Middle Mind,” which was the foundation for his book of the same name.

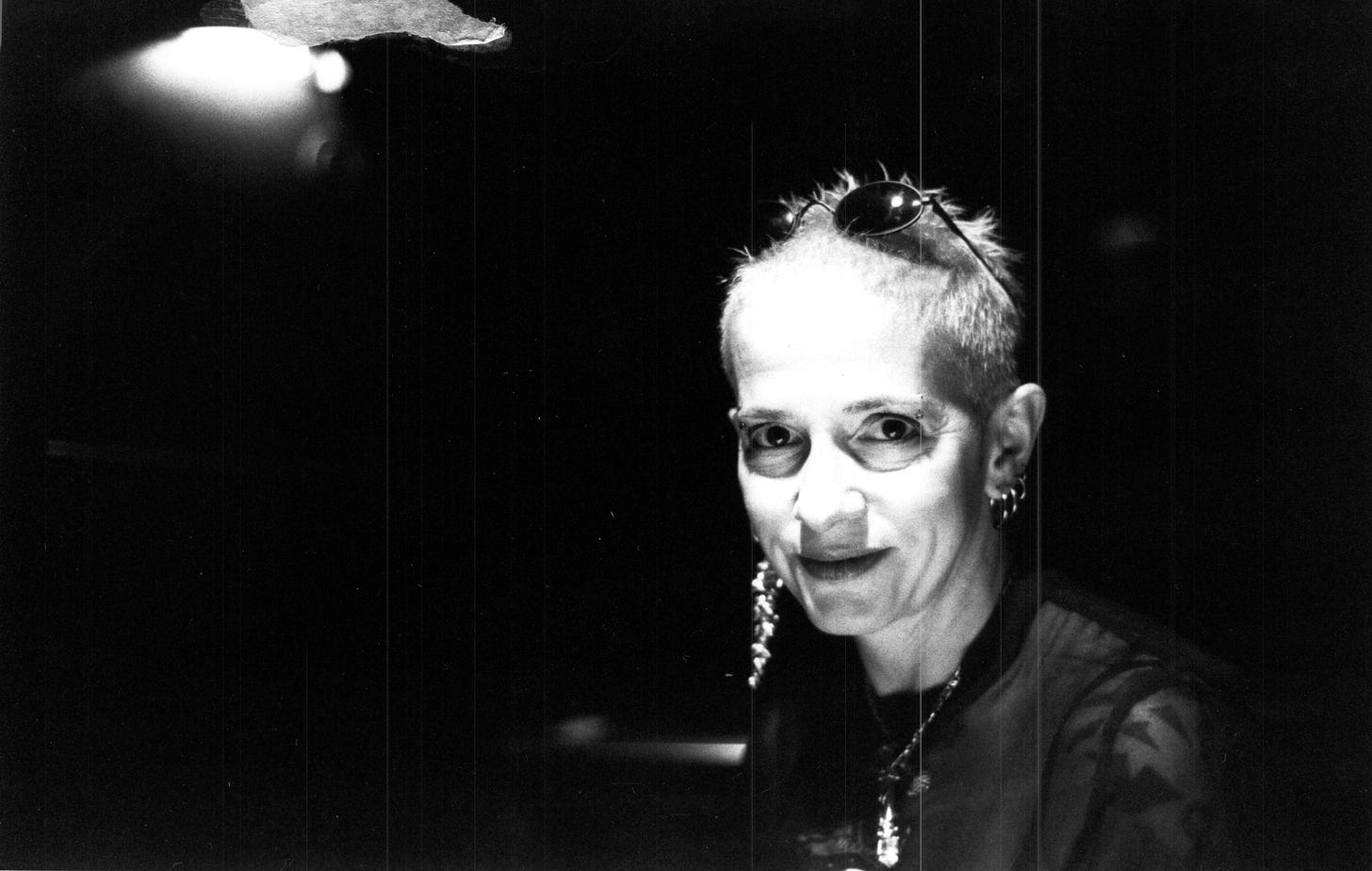

In terms of Kathleen Wheeler, she’s a professor emeritus at the University of Cambridge, and the author of several critical works that will be of interest to Dalkey Archive fans: “Modernist” Women Writers and Narrative Art; Romanticism, Pragmatism and Deconstruction; and, A Critical Guide to Twentieth-Century Women Novelists.

She was happy to see this essay resurface for new readers unfamiliar with Kathy Acker—something that encourages me to save more pieces from these old issues of Context that aren’t currently available online. Anyway—on to Acker!

Reading Kathy Acker

I opened my mouth, but no words. Only the words of others I saw, like ads, texts, psalms, from those who had attempted to persuade me into their systems. A power I did not want to possess. The Inquisition.

Well, no, not Acker; Ann Quin, actually, in her marvelous Tripticks. Not one of Acker’s “plagiarisms” either, although it could have been. She did remark, however, in Empire of the Senseless (1988) that “ten years ago it seemed . . . nonsense would attack the empire-making (empirical) empire of language, the prisons of meaning.” Maybe this was a “plagiarism”? Especially since she concluded that “nonsense, since it depended on sense, simply pointed back to the normalizing institutions.” On the same page, she wrote about past failure, about going beyond “deconstruction [which] is always a reactive thing . . . reinforcing the society you hate” (Hannibal Lecter, My Father). Earlier, in Empire of the Senseless, Acker wrote (copied? plagiarized?) that we do not “lovingly relate to each other in equality, whatever that is, or means, but out of needs for power and control. Humans relate to other humans by eating each other.” Kathy Goes to Haiti (1978) is a graphic account of this power/control dynamic. Margaret Atwood had, ten years earlier, humorously portrayed this conspicuous consumption of women in our society in her short novel, The Edible Woman (1969). Her character bakes a huge cake, shaped like her body, and gradually eats it all up, in an effort to communicate her awareness of and objection to this status quo. Like Atwood, Acker uses wit and humor in the service of a compelling call to her fellow humans to wake up to the tragedy of much of our lives. Tragicomedy is her genre, too, in many novels, such as those in the collection Portrait of an Eye (1992) and Literal Madness (1988).

“I need new instructions . . . new blood,” she wrote, since power and control relations are a “code of death.” In searching for a language and text “past failure” and “beyond deconstruction” (“I got sick of doing it”), Acker wrote of boredom, “borderdom,” and the transgression of borders. She wrote of poverty (as proverbial), and of their opposites, namely, wonder. (See her Bodies of Work: Essays, 1997, for some of her nonfiction writing.) She sought to articulate this idea of wonder—as at the basis of art and beauty—through myths and metaphors of the body, sex, travel, permanent and positive exile, and wandering. When asked, in an interview with Sylvere Lotringer (in Hannibal Lecter), what it meant to work “past failure” in a text, she said, “To go into the space of wonder . . . that’s what I like, all writers like. To have that sense of wonder.” “Spaces of wonder” are those “wild places”—geographical, intellectual, and bodily/emotional—places explored that go beyond known narratives, text, and experience. A space of wonder, one of those wild places, will be “a human society in a world which is beautiful, a society which wasn’t just disgust” (Empire of the Senseless). Someday, she argued, there will have to be another New World, and a new kind of woman/man/human being to live in its sunshine. Before these new realities an occur, before one can stand “there, in the sunlight,” we have to become explicitly aware of social programming. For Acker believes it has dehumanized us, and has created a “reality” more like a “hyperreal” realm of codes and simulacra, where desire has been programmed in a certain, repressive way, as, for example, she anatomizes in My Mother: Demonology, a Novel (1993) regarding heterosexual desires from the point of view of a woman.

Acker, like Jean Rhys fifty years earlier, broke through the boundaries of propriety in all areas:

Christ was right about publicans (and about sinners, too, in my opinion). They are nicer than other people—and I sincerely hope they will walk first into Heaven leaving the holy righteous and respectable outside looking very puzzled.

Rhys’s novels about the demimonde in Paris and London are instructive, as are Ann Quin’s, for reading Acker’s overtly outrageous challenges to the complex of power/money/prestige she attacked. Acker’s experimentation with every aspect of the novel—her frontal assault upon prevailing values and morals—rests on the belief that one must destroy the bastions of:

logocentrism and idealism, theology, all supports of the repressive society. Property’s pillars. Reason which always homogenizes and reduces, represses and unifies phenomena or actuality into what can be perceived and so controlled . . . Reason is alwasy in the service of the political and economic masters. It is here that literature strikes, at this base . . . [it] denounces and slashes apart the repressing machine at the level of the signified. (Empire of the Senseless)

Unlike Rhys, however, both Quin and Acker dispensed with almost all familiar conventions of the novel. They both sought to reveal the fact that familiar order and logic are much less native to our experience than we realize, whether we mean inner mental experience or the apparent order of nature and the “external” world. Sanity is, arguably, merely the most familiar form of irrationality. Both authors challenge conventional assumptions about individual identity. They also examine its construction, perpetration, and its breakdown, as for example in Quin’s Berg (1964) and Three (1966), and in Acker’s The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula and The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec by Henri Toulouse Lautrec (both in Portrait of an Eye). Like Jane Bowles, in her wonderful novel, Two Serious Ladies (1943), and in numerous of her witty short stories, Quin and Acker play with gender categories, as well as with stereotypes within gender which limit pleasure and creativity. Indeed, social programming is shown deliberately to prevent genuine individuality, since characters impose on each other and themselves roles and cliched forms of behavior.

Quin’s Berg, Three, Tripticks, and Passages are the most obvious literary precursors to Acker’s “wild places.” Jean Rhys’s representations of the demimonde—along with Stevie Smith’s wilder narrative and modernist experiments (especially in Over the Frontier, 1938)—are instructive, however, for the “tradition” within which Acker was working, as are such writers as Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. Yet Angela Carter and even more so Leslie Marmon Silko, in Almanac of the Dead (1991), provide an interesting and contemporary counterpoint to Acker's artistic, polymorphous perversity. More importantly Silk's writing articulates Acker’s own self-acknowledged fascination for dream and myth, particularly in the last decade of her life, when Acker was moving out of her earlier disruptive techniques into something “new.” Silko uses familiar magic realism and Native Indian myths to explode the delusions of respetable society in two of the most impressive novels of the last quarter century. Acker's artistic development parallels Silko’s own move, far away from “story” (in Ceremony, 1977) to episodic “narrative” (in Almanac of the Dead). Silko did manage, however, to wrest power away from conventional narrative writing with less obvious violence than Acker. Silko’s critique is more firmly located in apparent use of some conventions, in order to make the text more accessible and more apparently “legible.” This “legibility,” however, collapses beneath the scrutiny of close reading. Acker was also profoundly fascinated, like Silko, with the idea of magic worlds, “strange worlds,” those wild places:

I like that landscape much better. You're allowed to just move, you're allowed to wander. It's like travelling . . . I guess I just want to go on a journey and so I start with a sentence and then the language twists and turns and you don't even remember where you've been, you're always faced with the present. You're always going somewhere, you always end up somewhere. You want to be surprised. [my italics] (Hannibal Lecter)

Surprise, as Truman Capote had argued decades earlier in relation to Jane Bowles, is at the heart of aesthetic pleasure, along with that other element not normally associated with Acker, namely, beauty. “It’s all about beauty, isn't it?” said one contemporary artist recently when asked what he thought of recent experimentation in the visual arts. As Acker put it, it's all about a beautiful world, where power and control and consumption no longer run the show.

In this vein, the primitiveness of the body takes the place of the “I” as subject in many of Acker’s early texts. Yet she also described herself as a “conceptualist”; hence, there is no room for any mind/body dualism in Acker's writing or in her representations of ordinary experience. In spite of all the attacks on society et al., she sees herself as, in a weird way, a kind of humanist, who has gone from primitive instinctual deconstruction, through, and then beyond, theory. In In Memoriam to Identity (1990) and Eurydice in the Underworld (1997), she explored, explicitly, the myth of romantic love which had run throughout her work since her earliest writing, and which has such a crushing effect on the development of viable individualities. But, after that, she wanted to move on, like Silko and Quin and others, into something different.

Acker has explored the limits of experimental fiction more, perhaps, than any other writer published today. Like William Blake before her (another iconoclast thought during his time to be so outrageous, sexually explicit, and indecorous as to be held mad for some 150 years), she explicitly appealed to the importance of shock in awakening her readers from the sleep of familiarity—Blake’s Ulro. She blasts out a clarion call to awaken us from the stereotyped selves, roles, and forms of behavior that so horrifyingly, convincingly pass for our own personal experience. Her novels are ribald exposures, as in Pussy, King of the Pirates (1996), of the forces both within the psyche (“mind-forged manacles”) and without, which construct and dominate identity through gender, class, race, and so on. Her experiments represent a quest to find out what could liberate us from these habitual fictions we call reality and ordinary life. She is famous for her deconstructions of narrative personae, of story or plot, of characterization, thematics, and so on. She is well-known for her Foucault-like articulations of the dynamics of political, social, and psychological power, and was for a time notorious for satirizing realist, conventional feminist fiction (Hello, I'm Erica Jong, 1982) which, she argued, props up the very structures it seeks to challenge. Her techniques of plagiarism, her constant challenges to “intellectual property”—which got her into serious legal trouble in both England and Germany—are favorite topics for readers. Others are her erotics, or near (if not actual) pornographics, her blasts at social decorum as well as literary proprieties, her incoherent thematics, plotless texts, chaotic character non-identities (taking the “anti-novel” to its most extreme form), her mix of autobiography, fact, and fiction, or madness and sanity. These well-known narrative experiments are characteristic of most of her work; they are designed to shock the reader out of complacency, much like Blake: “You're dealing with shock. To me nothing's interesting unless it's slightly shocking. Otherwise I am just dealing with my own habits. Lulled into habits again and again. It is good to be shocked.”

What has often been overlooked, however, is the deeply-moving humanity at the basis of Acker's writing—which should put paid to notions that such experimental writing is somehow apolitical and therefore escapist. Recent extreme forms of experimentation in theory and in fiction, such as postmodernism, are said by many to be apolitical, because they do not discuss explicit political topics overtly. This notion is an indication of the misguided lengths to which critics—unconsciously committed to tradition (whatever their concious assertions)—will go in order to perpetuate confusion, inequality, and the status quo. Acker, taking society and us individuals as a series of interrelated texts, “bodies of writing,” seeks in her writing to achieve a direct connection between herself and the reader. As William Burroughs put it, “Her author moves and shifts before you can know who ‘you’ are, and that gives her work the power to mirror the reader’s soul.” Her efforts to decentralize power and reappropriate it are in the service of a more humane way of constructing societies and personal identities. There, in those sunlit places, those wild places, those spaces of wonder, those moments of beauty, people will be able to seek out more fulfilling ways of “realizing” themselves, their relationships with others, and their desires/pleasures/needs. Acker, like William Blake and others, knew sexual repression was the fundamental social instrument for the imprisonment of the human body/spirit. Escape for all of us from boredom and poverty—whether spiritual or material—was a constant quest for her, as it was for Jean Rhys and Ann Quin. Regrettably, exactly like all the writers mentioned here, Acker has often been misread and misunderstood, mixed up with her characters, thought to be hard, unfeeling. If the views of some critics prevail, that Acker’s writing is “rubbish,” it will only be we who lose. She died of breast cancer four years ago. [Ed. Note: Acker died in 1997.]

Kathleen Wheeler’s “Reading Kathy Acker,” appeared in Context No. 9.

great to see a comparison between Acker and Quin, will check out the podcast