In mid-December 2020, I returned to the Dalkey Archive Press office in Funks Grove, Illinois for the first time in fourteen years. Together with Will Evans of Deep Vellum, we were there to go through all the files, figure out what we could about existing contracts, mail orders from the past month, and generally take stock.

Driving out there, I wasn’t sure about what we would find, or how I would feel about it. It wasn’t like I left under the best of circumstances (the almost relocation of Dalkey Archive to the University of Rochester is a story for another day), but in the summer of 2019, I had reached out to John O’Brien, we had put aside our past differences, and we were working to try and find a way for Dalkey’s true legacy—its incredible backlist—to survive his eventual passing.

This visit was supposed to be a reunion of sorts. A time to sit around, reminisce about publishing circa 2004, and brainstorm about ways to realize Dalkey’s mission by joining forces and reimagining what nonprofit publishing can be.

Instead, John passed away in November, and Will and I were left going through John’s desk, trying to make sense out of the boxes dumped in the warehouse, taking stock of what Dalkey had been publishing over the last few years.

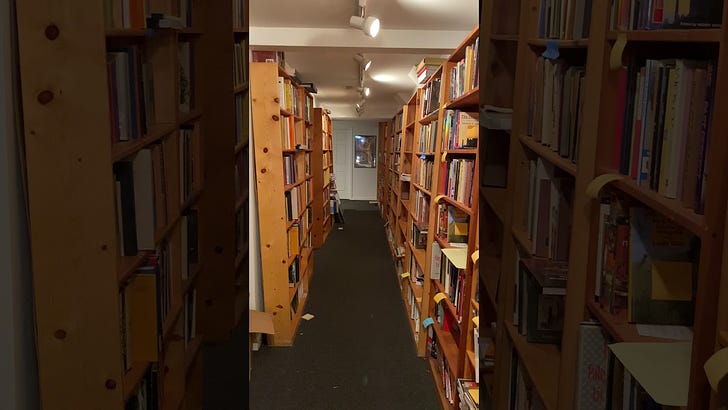

My first visit back to the offices—which were in the basement of John’s house—was a bit of a surprise. You can see it all in this video, but this place (ca. 2006) was immaculately organized, and populated with employees—an efficient, fantastic small press.

The shed/warehouse was where the real chaos was, though. We believe all the boxes stacked by the front were delivered from Texas after Dalkey left the University of Houston-Victoria. This warehouse was built back in the early 2000s to store overstock so we wouldn’t have to pay our distributor for excess inventory or destroy the copies, thus helping us achieve our goal of keeping these books in print forever.

In addition to processing the torrent of conflicting emotions—anyone who worked for John knows exactly what I mean—I had a lot of time to think about Dalkey Archive and what it’s meant as a press and cultural influence. Which was far more inspiring than I had expected . . .

Being among all of those books (the ones Dalkey did and the ones John kept around because they were important or interesting) reminded me of how this press was always supposed to be a “living archive.” I’ll get into this in far more detail in the next post, but a core piece of John’s idea for the survival of the press was an excellently curated backlist that, by keeping the titles in print forever, would result in books and authors that were rediscovered by future generations of readers. It was rare for a Dalkey book to have a sizable audience from day one, but over years, decades even, the readership for a book would grow and, who knows, through changes in reading tastes, could suddenly take off years after publication.

Over the past four decades, so much has changed about publishing and bookselling, reading habits and how books are discovered and popularized. Several of the authors Dalkey rescued over the first few decades of its existence have come back into favor recently. Annie Ernaux and Jon Fosse immediately come to mind, but this is a catalogue that also includes William H. Gass, Marguerite Young (whose Miss MacIntosh, My Darling would’ve been a pandemic blockbuster had there been copies available), and Gertrude Stein. Diane Williams has a few collections with Dalkey. And back in 2003, I edited the first collection of Deborah Levy’s stories to come out in the U.S., a follow-up to the 1999 publication of Billy and Girl. (Still my favorite of her books.) And for every Flann O’Brien and David Markson who found their audience, there are a dozen Dalkey titles sitting right there, ready to blow you away.

Poor Will Evans had to spend so many hours listening to me drone on about spectacular books that I had totally forgotten about—many of which he had never heard of. And every one of these books had a story behind it. How John came to publish the cartoons of Nicholas Wadley actually stems from a conversation with the Dutch publisher of Harry Potter. Some books stemmed from personal connections, some from editorial trips around the world, others thanks to funding, some because they just “deserve to be in print.”

These stories, about these books, is what prompted me to start thinking about this possible project. Not only could it be a way to honor John’s wisdom and unique approach to publishing, but a fantastic way to rediscover any number of great books and authors—and to share them with you.

My knowledge of Dalkey’s list really has its limits, though. I left in December 2006, saw a lot of books I had helped acquire (or at least knew about) come out over the ensuing half-dozen years, then . . . silence. Trying to collect a single copy of every Dalkey title has brought hundreds, hundreds, of books to my attention that I know nothing about. Titles that slipped through the cracks over the past few years as the business side of Dalkey Archive went into a tailspin.

Which brings me to the other impetus for wanting to start this multimedia project: To document the rise and fall of the press itself. There isn’t a solid history of nonprofit publishing in America (hit me up if I’m wrong), and so many of the key players who helped professionalize and expand this field during the 1990s are no longer with us. And so many of the stories and lessons from that time were transmitted orally, from publisher to mentee. That history—how it shaped the nonprofit publishing world and the overall reception of literature—can be fascinating, especially given how colorful small press publishers tend to be. The growth and transformation of nonprofit publishing has a lot to say about the ways in which cultural consumption has evolved over the past few decades of consolidation and reliance on best-sellers.

So over the course of god only knows how many posts mixing together anecdotes, interviews, podcasts, videos, literary analysis, and more, I want to really dig through the Dalkey Archive. Its history, John’s vision, the amazing books, the influence of CONTEXT and the Review of Contemporary Fiction, the controversies, the failed ideas, the ambition, and the impact. Dalkey Archive is a special press whose legacy embodies far more than Voices from Chernobyl and Flann O’Brien.

This is such a heavy lift. Nan, just want to extend my gratitude and enthusiasm for you, Will, and everyone involved with uplifting and rediscovering everything for both republication and preservation purposes. I will be following from afar!

I was the production manager back when DAP moved to UHV & when I started (October 2014?) it was just me & Jake Snyder in John's basement—talk about a skeleton crew. Mikhail was doing layout from Brooklyn (before he got fired for being too expensive & I was left to do it all with no background in design, basically "go teach yourself InDesign so you can lay out all the books") and Jeremy Davies was all by himself in what was left of the Champaign office, which I had to almost singlehandedly pack up & move to either storage, Victoria, or John's house. Those shelves weren't up in the back warehouse in Funk's Grove when I was there—I moved a bunch of the inventory there from Champaign, got the UHaul stuck in the mud—we had the shelving pieces but there was no one to put it up; looks a lot better now. I also assembled a bunch of that furniture down in the basement as John wanted to possibly open it up as the main office if UHV didn't come through (which it looks like it ultimately didn't, but that was predictable from the start). I left (or was fired, depending on the story you choose to believe) in summer 2016, just before the election, an Illinois boy stuck in Texas. Good times I suppose.