The DNA of Dalkey Archive Press

Exploring John O'Brien's mission and the first Dalkey publication

Why do we read what we read?

It’s easy to come up with reasons for what we choose to read, explanations to retroactively explain why a particular book suddenly took off—great cover, compelling blurb, peer pressure, entertainment, forthcoming Netflix series, serendipity, chance—but all of that depends on which books are available.

The conversation about gatekeepers throughout the publishing industry (agents, editors, book reviewers, booksellers) is one that’s definitely worth having (especially when considering the gender, race, and sexual orientation of the people in charge), but I want to start from something more basic and all-encompassing: the marketplace.

The market—or projections about it—are behind almost every decision in for profit publishing. The size of an advance, a book’s marketing budget, and, most relevant to this post, whether or not a book remains in print.

Thanks to print on demand technology, nowadays, it’s quite possible to keep books in print forever. (Whether or not POD is the best way for a book to reach its largest possible audience is another question.) Obviously, that hasn’t always been the case. Print runs are always a nightmare: overprint and you have to pay to store a bunch of books that aren’t selling, under-estimate demand and you miss out on the economies of scale, cutting into potential profits. (Having chickened out on printing 6,000 copies of Zone only to sell out of the first 3,500 copies in four weeks was a harsh way to learn that latter lesson. One that probably contributed to losing Mathias Énard as an author.)

For profit presses are very keyed in on their inventory levels. There’s no financial advantage to storing extra copies of most books, so if a title isn’t moving after a certain period of time (a year, a couple years), its extra copies are likely to be pulped or remaindered. Sell off excess stock and put the book out of print. Focus on selling more of the titles that are doing well in the marketplace (by reissuing the book with a new cover or new introduction, for example, or making a special backlist offer to bookstores), and get rid of the dead weight.

To make this as specific as possible, in addition to maintaining a warehouse in McLean, IL, Dalkey was paying $10,000 a month for excess, slow-moving inventory. We kept some copies of all of the titles, but pulped a significant number in an attempt to get the overall annual inventory charges under $50,000.

These rules of inventory management are all M.B.A. logical, but it really became a crucial cultural issue in 1983, thanks to Thor Power Tool Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. (Which, yes, I know sounds like some sort of joke.) A complete analysis of the ruling and its impact on corporate accounting by Kevin O’Donnell, Jr.’s is available here, but in brief, here’s the key issue: prior to this ruling, corporations exploited a loophole in tax law to increase their cost of goods sold—and thus reduce their taxable income—by reducing the value of their slow-moving inventory. (Instead of counting the value of all the books in inventory, they counted the percentage likely to sell.) Although this seems like a really minor accounting detail, it’s one of the biggest factors leading to the existence of Dalkey Archive Press, New York Review Books, and anyone else specializing in reprints of out of print books.

Q: Why did you start the Review of Contemporary Fiction?

A: The writers I was interested in—such people as Gilbert Sorrentino, Paul Metcalf, Douglas Woolf, Wallace Markfield, Luisa Valenzuela—were not being written about. Even though reading itself is a solitary experience, the impulse afterwards or even during is to want to talk to someone about the book, even if this “talking” takes the form of reading what critics have to say. But no one was writing about these novelists, and it was even difficult for me to write about them with any expectation that what I wrote would get published in journals at that time. If you wrote the 5,000th essay on Saul Bellow, you had a pretty good chance of getting it published because editors knew who he was and so publishing yet another essay on Bellow was safe. But they didn’t know who Douglas Woolf was, nor did they very much care about not knowing who he was. So, the critical establishment (however you want to define this, from academic journals to the New York Times Book Review) had a lock on what writers would be covered, as well as how they would be covered. One afternoon, Paul Metcalf was visiting me during one of his layovers at O’Hare airport, a habit he had gotten into in his trips across America. This particular afternoon, sometime in the spring of 1980, we were complaining about the state of literary criticism and said that someone had to start a magazine that would cover the writers who were being excluded. I decided that afternoon that I would be the one.

Over the next several months I mapped out which writers I wanted to devote issues of the magazine to, and also decided that the magazine would last for five years, feeling five years was enough time to get said what I wanted said and that at the end of that time, I would be ready to pack it in. I scheduled the first issue for the spring of 1981 and spent the next several months writing to people to ask them to contribute to various issues I had planned, as well as trying to learn how one goes about publishing a magazine. I didn’t have a clue about publishing—everything from copyright law to printing—and there was no one and no place in Chicago where you could go to ask about such things, even though there were a number of people doing literary magazines and small press books. It was, and still is, a very scattered community, and you can live in Chicago for years without meeting your “colleagues.” I had to learn everything the hard way.

So I started the Review out of a sense of isolation, as well as a kind of outrage at the fact that books and authors were reduced only to marketplace value. And I should say that, from the start, I wanted the magazine to break down the artificial barriers that exist among countries and cultures. It was my view then and now that one can’t properly come to terms with contemporary writing without seeing it in an international context, and it’s also my view that Americans generally don’t want to know anything about the world outside the United States unless they are planning a vacation.

Q: How did you get from the Review to starting Dalkey Archive Press?

A: The Press was never quite planned; I more or less backed into it, because there is no way that any reasonable person could start such a press with the expectation that it would last. Within three to four years after the Review began, there was money left over because there was almost no overhead involved with the Review except for printing bills. I decided that, with this money, it would be nice to reprint a few books, ones that really didn’t have much of a chance of ever getting back into print through a commercial house and ones that were perfect examples of the kind of fiction that the Review was championing. Among the first few books were Gilbert Sorrentino’s Splendide-Hôtel, Nicholas Mosley’s Impossible Object, and Douglas Woolf’s Wall to Wall. In fact, all of these authors had been featured in the Review, and yet many or most of their books were out of print. So the Press started with the intention of restoring to print “just a few books.” But then within a year or two, a few new manuscripts arrived, ones that deserved to be in print but ones that no other publisher would touch. The relationship between the Review and the Press is this: the Review was providing criticism on overlooked writers, and the Press was in many cases publishing those same writers, or writers who belonged to a similar tradition.

Over the years my hope for the Press was that it would be the “best” literary publisher in the country, even if that honor might be by way of default. Whether it was through reprints or original works, I wanted the Press to define the contemporary period, or at least what I saw as what was most important in the contemporary period. Further, I wanted these books permanently protected, which is why from the start the Press has kept all of its fiction in print, regardless of sales. And as with the Review, I wanted the books to represent what was happening around the world rather than more or less being confined to the United States. Like the Review, Dalkey Archive Press was and is a hopelessly quixotic venture.

Two things stand out to me from this interview:

1) The idea of community as the impetus for getting into publishing. This is something that Chris Fishbach, formerly of Coffee House Press, would bring attention to, but printing is not publishing. From its inception, the Review of Contemporary Fiction (and by extension, Dalkey Archive Press) was all about creating a community around a particular book or author. And back in the 1980s and 90s, that community was created through face-to-face interactions. Booksellers were more important than ever, with no Amazon, no Twitter, no Instagram. The Modern Languages Association annual conference, along with the American Booksellers Association one and various regional ABAs, were key to creating an audience, meeting readers, expanding this community. This is all obvious, but in 2020-21 it seems more quaint than ever.

2) To “permanently protect” literature that isn’t supported by the marketplace is the ethos of nonprofit publishing at its finest. There are a number of activities that can get a publishing house nonprofit status, but the most admirable (in my opinion) is doing something that no one else will do. (Mark it. That’s the first shade thrown on this Substack.) And at the time that the Review of Contemporary Fiction and Dalkey Archive Press came into existence, no one else would reprint these “obscure,” “innovative,” “hard-to-sell” books. These are, quite literally, books that couldn’t be supported by sales alone. Or, at least not sales of the level necessary for big presses of the time to keep in print. Which, to put this into a really weird context, includes New Directions, the original publisher of Sorrentino’s Splendide-Hôtel, the first book to come out from Dalkey Archive.

For more information about John O’Brien, please check out this episode of the Trafika Europe radio show/podcast “Black on White.”

John used to regularly talk about the “Dalkey DNA.” His belief—which, to be fair, he reinforced through his actions—was that any organization had a “DNA,” a way of being that was baked into the culture and very difficult to change.

At Dalkey Archive, this meant that “employees were more concerned with editorial than marketing and sales,” a statement that became almost tautological through the Press’s hiring process.

What interests me though, is the corollary to that statement: Dalkey’s editorial focus was pretty locked in from book number one.

It’s interesting to look back at the first books published by independent presses. For Open Letter, it was Dubravka Ugresic’s Nobody’s Home, translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać. New York Review Books? Peasants and Other Stories by Anton Chekhov and Constance Garnette. Deep Vellum’s first was Texas: The Great Theft by Carmen Boullosa and Samantha Schnee. Such Small Hands by Andrés Barba and Lisa Dillman was the first from Transit. According to Wikipedia, New Directions started with anthologies of new writing. Peter Conners from BOA Editions frequently tells the story of their first title, The Fuhrer Bunker: A Cycle of Poems in Progress by W. D. Snodgrass. Melville House came to be in 2001 with Poetry After 9/11.

All of these track.

Every press is multi-faceted; every publisher has a particular aesthetic they want to promote.

And for John, he wanted to throw rocks at the establishment. The marketplace is tilted in directions that he didn’t agree with, mostly because the advantages granted certain presses and books aren’t tied to literary quality, but to something else. Instead of just giving up, he wanted to disrupt common practices, and alter the conversation about literary fiction. About why we read what we read.

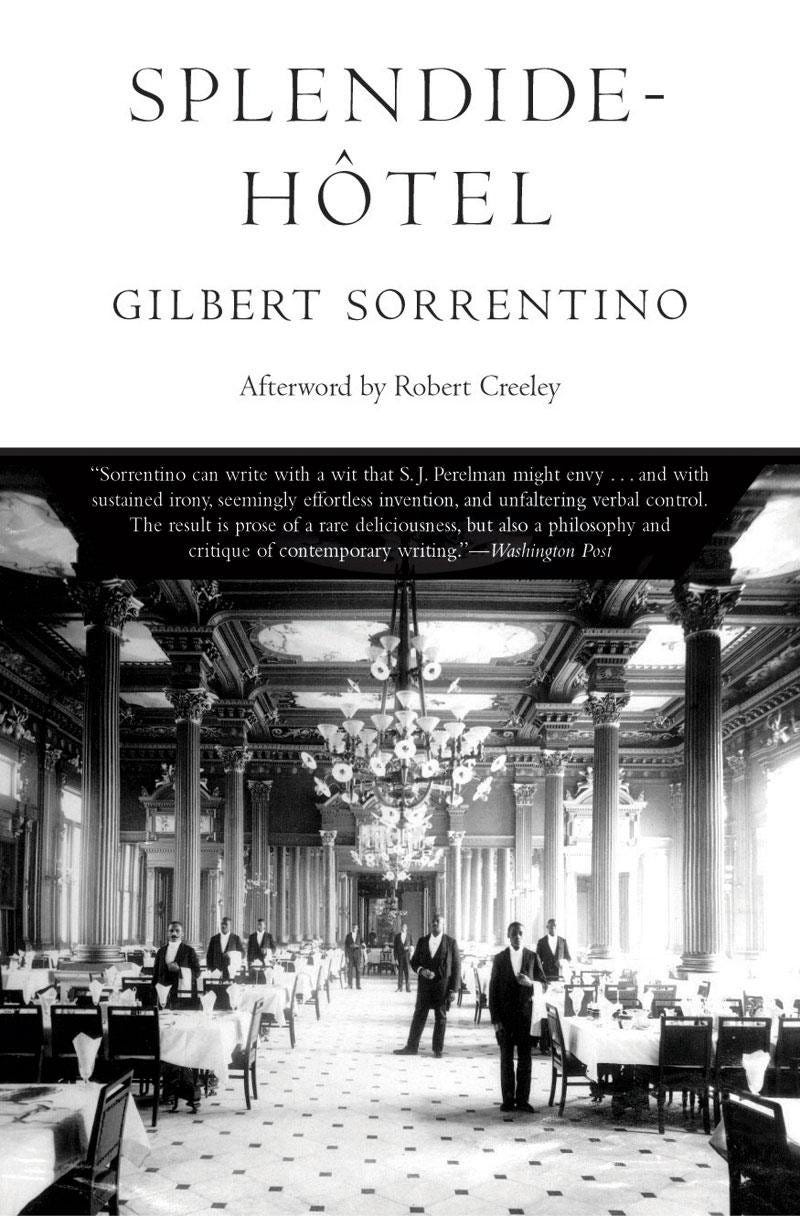

Above you can see the first edition of the first book Dalkey Archive ever published. Design-wise, this is a straight-up ripoff of Gallimard Editions, right down to the complete lack of jacket copy. It’s Fitzcarraldo Editions before Fitzcarraldo said that non-covers were cool.

The most interesting aspect? “THE” Dalkey Archive Press. Given how many jokes John made about misspellings and mispronunciations of the press’s name—Delkey Archives, Dakley Archive, etc.—this is kind of amazing.

Gilbert Sorrentino was one of John’s lodestars. The way he wrote—imaginative and precise and satirical and aware of fiction’s limitations—and his thoughts about literary and literary aesthetics as a whole.

I remember two specific things that John told me about Sorrentino. The first was that Gil said there was “nothing to learn about writing by reading Dostoevsky,” which, in my older age, I 100% stand behind.

He also talked about how Gil had no depth perception, which is why his writing was so concerned with the “there,” the surface instead of the metaphor. (John hated Pynchon for being the exact opposite of this; John never saw my Crying of Lot 49 tattoo.)

(Bonus Memory: I helped put together Something Said, Gil’s collection of essays. I scanned in hundreds of pages at a time with optical character recognition technology was very hit-or-miss, and then proofed them as carefully as could be. Last minute, before the books was going to go to print, Sorrentino found a typo. A mixture of bad proofing skills and a “rn” vs “m” scanning error lead to this book almost containing a reference to Wendell Berry being into cornholing.)

Splendide-Hôtel defines the Dalkey aesthetic in two ways: form over plot and legacy of this tradition.

It’s similar to On Being Blue by William H. Gass in the sense that it’s part fiction, part essay. A meditation on each letter of the alphabet, Sorrentino’s third work of fiction, is inspired by Rimbaud’s “After the Flood” (“And Hotel Splendid was built / in the chaos of ice and of the polar night”) and first came out from New Directions in 1973. Dalkey reissued it in 1984 with an afterword by Robert Creeley (“I’ve been trying to pay respects to this work since first reading it in someone else’s home . . . ”). It’s also an homage to William Carlos Williams (another ND connection), and is by turns funny, provocative, elusive, and beautiful. Plus, it includes baseball,.

In a way, it’s the ultimate Dalkey Archive book.

I

Did the poet not warn us of his later career when he said, “I am the master of silence”? Of course. In this I resides his absolute truth. Distrust all people who think that the artist does not mean what he says. For him, for him alone, this stringent letter obeys all commands.

Now, let us assume the installation of the fake, shielded by the letter I, behind which, of course, corruption, corruption. The darling of the market composes a novel in the first person—God forgive him—is borne forward by the protagonist: he, Rimbaud, tells the story of his life. The writer, whom I take to be a professional of limited gifts, “writes” The Illuminations within the body of this wretched volume. And invents—the Splendide-Hôtel! “I have invented the the exquisite figure of the Splendide-Hôtel,” he has the poet say. One imagines this comfortable son of a bitch thinking of himself as Arthur Rimbaud. As he places that I on the paper he is, in all his mediocrity, more puissant than the shade that he has turned into a “character.”

I descend further. Conceive of the idea of some current star of the film world, some “personality,” playing Arthur Rimbaud in a movie geared to the expression of Youth in Revolt and Freedom. Ah God! beware the raising of the ghosts of dead poets, damned Catholics hungry for revenge: cadaver of M. Rimbaud drifting toward the set. One imagines starlets running in terror, etc. All those lettuce and tomato sandwiches and containers of yogurt crushed under foot. The director stand petrified in fright, his mouth open: into which buzzes the black A of a fly.

Snarky, anti-bullshit art, a touch elitist . . . 100% a Dalkey book.

Also: It’s concerned with legacy. John’s idea of the “superior” literary tradition ran through Rabelais, Sterne, Joyce (see The Other Irish Tradition), and Gilbert Sorrentino embodies this fully.

In 2001, Dalkey Archive printed a second edition of this book, with this particular cover—a cover that Gil and John picked out way back when as the perfect photo for this book if it every got reprinted with an actual cover.

Which is from the Palmer House Grand Dining Room, circa 1880. And which ties into this:

W

An artist whom I have known for fifteen years has for some time been painting and drawing pictures of waiters arrested in the varied aspects of their work. These are profoundly moving pictures of desperate men, locked into a profession that offers little succor. They are totally beaten, thoroughly defeated, yet they manage to perform their duties with a bravado that is nothing short of heroic. The expressions and postures of the waiters are tragic, they stand, staring out of the pictures, their faces acute delineations of pain and humiliation. Some of them rush through the space of the pictures, trays above their heads, in a shower of falling china, glasses, and silverware. Some lean against each other in exhaustion. Some stand, immobile, trays under arms, blowing smoke rings. And others, wild-eyed, fling their arms and legs about uncontrollably. It is, I think, safe to say that they are all on the edge of insanity.

Nowhere does one see a diner.

I assure you that these are not “real” waiters. They are the waiters of the artist’s imagination. They are devastating, they make one uncomfortable, they are totally unlike any waiters that anyone will ever see. And yet—and yet surely they must be the waiters employed by the Splendide. By an act of the imagination, the artist has driven through the apparent niceties of restaurant dining to reveal the bewildered rage and madness therein. One who has seen these pictures can never again dine out without suspecting that the waiters are all involved in a terrific charade. Their irrational behavior and broken spirits do exist: in the imagination, purified against all change: in the Splendide. These clearly constructed figures of despair, willed into existence by an act of the imagination, allow us to “read” the activities of “real” waiters acutely. They stand revealed. This subtlety is the artist’s entire achievement. Through the employment of the imagination he lays bare the mundane. The painter, who may have seen the necessity for his project in the brief, single turn of a waiter’s wrist, must certainly agree with the poet who writes, in a work specifically concerned with the imagination:

It is only in isolate flecks that

something

is given off

So I come again to Williams, another w for this chapter.

Williams Carlos Williams was eight years old when Arthur Rimbaud died. It pleases me to see a slender but absolute continuity between the work of the damned Frenchman and the patronized American.

Thus, the Dalkey editorial DNA. In two passages.

Coming Next: An investigation into Bottom’s Dream by Arno Schmidt and John E. Woods.

We interviewed Kevin Mattson today, author of We're Not Here to Entertain, a chronicle of punk culture c.1980-85. Tons of zine history in there. All those zines were about creating a close-knit culture and community in the way O'Brien talks about in that interview, a few of them even discussing high minded lit and philosophy. You know if he was tuned in to that scene at all? If he took any pages out of their playbooks or vice versa?

I once had a course on publishing history by a former editor at Penguin (and brother to Rosalind Franklin) who told the class his idea of the perfect cover was just the title and author. The rest was mercantile trash.