Greetings my reader in a century to come in a thousand years give me your hand and tell me that I’m likeable

—Pierre Albert-Birot

Despite the fact that, at least based on the sales numbers (just over 300 hardcovers, just under 600 paperbacks), I don’t think a lot of readers are familiar with Pierre Albert-Birot (or PAB for short), he holds a special place in the Dalkey Archive Pantheon for me.

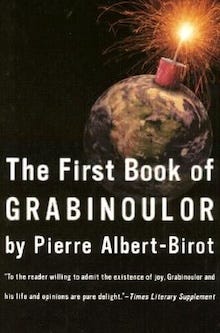

Martin Riker (co-founder of Dorothy, longtime Dalkey employee, author of Samuel Johnson's Eternal Return and The Guest Lecture) talked up Pierre Albert-Birot’s only “novel” to be published in English, The First Book of Grabinoulor translated by Barbara Wright, on one of my first days at the press. It was July 2000 and a paperback reissue of the 1987 hardcover—a project I believe Marty spearheaded—was just coming out. At the time, I had never heard of PAB, and glancing through the book, I stumbled over the concrete poetry section, but although I assumed it was a book that I wouldn’t understand, Marty was so hyped on it that I took a copy and read it as fast as I could.

Which was a mistake. I talk about the benefits of reading slowly, and techniques for how writers force you to slow down—something we can all gain from these days—frequently on the Two Month Review podcast, and if there’s a patient zero for that concept for me, it may well be The First Book of Grabinolour.

Grabinoulor wakes up

That morning Grabinolour woke up with his heart full of sunshine and his nose standing up straight in the middle of his face a sign of fine weather and just a glance at his friendly blanket showed that it wasn’t only his mind that was reaching out to life in virile expectation

While he was happily washing his hairy body he went jumping naked through the woods and published a book then he put his clothes on and even had some compliments from his implacable friend the mirror which isn’t in the habit of paying them lightly then he was immense and went into the street where two girls were going by on bicycles so he saw some legs and some undies and he didn’t know which girl to choose now while this battle still raging inside him the objects of his desire had all but disappeared and it infuriated him to see that the road was turning round and going to get them so the part of him that wanted the white dress and the black hair lashed out so decisively that the other part was killed and so thoroughly annihilated that no one has ever been able to find it either in this world or the other

Not really the sort of book you can skim, at least not in any meaningful way. If it’s not the lack of punctuation that will trip you up, the multiple ways to parse segments of the paragraph will have you doubling back, if not to recontextualize a fragment (the overlap of “[he] went into the street where two girls were going by on bicycles,” and “two girls were going by on bicycles so he saw some legs and some undies” subtly creates two different movements, at least to me) but because events can happen at a breakneck pace.

Here’s the end of the chapter quoted above:

Grabinolour is much stronger than any cogwheels and especially on the days when his nose is erect as it was that morning for example so then so then he took the girl he’d chosen and went on his way almost immediately he met another girl who was on foot and she was alone Grabinolour didn’t have an opponent so he chose her at first sight and went on more and more happily and even though the shadows of the trees tried to bar his way he passed through Paris where he didn’t have any adventures because he was thinking of something else and immediately came back into the Atlantic sub-prefecture he lived in the town of glorious idleness even so while he was walking along the top of a cliff he built a house admirably suited to both winter and summer and painted it yellow and green and for this he needed neither ladders nor pots of paint nor brushes and while he was busy building a machine to transform the movement of the sea into electric light he lay down on the sand and nearly left for Spain but an ant stopped him for Grabinoulor is kind and observant and the ant was finding it very difficult to climb up the mountain which kept trickling down under its feet and that was when he made a hole with his stick to see what the ant would do but he was too strong he dug too deeply and his stick went right through to the other side now as he was very fond of this stick which was itself extremely attached to him he followed it but as the town he came to was in total darkness and fast asleep and he didn’t know if he was afraid that he might be taken for a murderer so he came straight back up to his side with his stick but the sun had lain down in his place and he didn’t want to disturb it so he went off into next year to see whether the war was over and when he got home with a light step he said to his wife are we going to have lunch soon I’m starving

Phew. That “so then so then” feels like a kid taking a pause right before launching into hyper blast of a story with too many details and no explanation and seemingly no end. What is the “war” that he’s checking up on after go “off into next year”? Where are we after he “nearly left for Spain”? I mean, who cares, for me it’s “he was afraid that he might be taken for a murderer” that cracks me up. This sort of illogical internal conclusion is something that shows up a lot in the French minimalist writers like in Toussaint’s Television or Oster’s In the Train, in which part of the joy of reading these books is for the wacky ways in which the narrator views, understands, and acts in the world.

Western by Christine Montalbetti (receiving her own post in a few weeks), is another book that has to be read slowly. But although ants show up in the first chapter of her book as well, her approach—which, as you’ll see, is equally meandering—is to slow everything down, exploring every moment through an unusual lens for pages and pages, a distinct contrast with the total breathlessness of Pierre Albert-Birot’s style.

And those paragraphs above are from page one of The First Book of Grabinolour, the first of six books in the Grabinolour series, all of which are collected in one volume that totals 995 pages.

Who was this guy?

Everything I know about Pierre Albert-Birot’s life and thoughts on writing come from Barbara Wright’s introduction to the book, a postface from his widow, and the work of Debra Kelly, who edited Barbara Wright: Translation as Art and reworked some of the material from her book, Pierre Albert-Birot: A Poetics in Movement, A Poetics of Movement into the essay, “Grabinolour Has Fun with Language and Makes New Friends: The First Book of Grabinolour and Beyond.”

In terms of biographical facts, he was born in 1876, died in 1967, and was a painter and sculptor before becoming a poet and editor. From Kelly’s essay:

Albert-Birot had lived alongside the adventure of modernity, seemingly unmoved by the artistic revolution of Cubism and untouched by the poets who were to become some of the contributors to his avant-garde revue SIC, until his meeting in 1915 with the Italian Futurist painter, Gino Severini and through him, with Apollinaire.

According to Wikipedia, he and Apollinaire came up with the term “surrealist,” in relation to the play Les Mamelles de Tirésias, which Apollinaire wrote and Albert-Birot directed, which, in some alternate universe, is enough for all of PAB’s works to be translated into English. Instead, all we have is this one slim volume of Grabinolour and 31 Pocket Poems which Barbara Wright also translated.

Which is sort of surprising. Although this book was originally published by Atlas in the UK—in 1986, with Dalkey Archive’s hardcover coming out a year later—it feels like such a Dalkey book. The boisterous, Rabelaisian voice bouncing off the page, all the dirty bits, the way that he helped break with conventional forms to create a whole world unto itself . . . And John loved and respected Barbara. Apparently one of their first communications was a series of letters sent back and forth across the Atlantic debating the ways to find an English in translation that is neither marked as obviously British, or totally American—something they brought up every time we got together. She was so warm and witty and brilliant, and if she had asked John to publish the other 5 volumes, he would most definitely have agreed.

Although given Barbara’s meticulous approach to producing the perfect translation, this would’ve taken her at least four decades to complete . . .

Grabinolour—it’s impossible to speak about it. It’s a name I found from its musical sound. I can say that this book came to me one morning, in the middle of a forest by the sea, in the south west of France, during the war. There I was, away from everything, and one morning, just like that . . . the general idea of the book came to me . . . So far, there must be six volumes written, and pretty substantial volumes at that, as they contain not a single comma or full stop. They are masses, verbal masses. I work very little on them, that’s to say for one hour every evening, but after forty years, this adds up to quite a few lines!

Given that we only have this one 90-page volume, it’s hard for monolingual me to be able to say anything about the world PAB created. That said, according to Kelly, “this First Book holds the essential keys to an understanding of what would follow.” I’m not going to detail every thing she points out—for that you’ll need to read the book—but there are a couple concepts related to the chapter above that might provide a better appreciation of what he was up to—and the challenges Barbara Wright faced in translating this.

One is simply the idea of excess. Grabinoulor is not at all efficient. Rather than getting to the whale, PAB dances around, adding adventure after adventure, sending his narrator on a quest that can be mythic (see chapter two when his attempt to make a statuette level leads to him reshaping the Earth) or mundane (see chapter 22 which opens with Grabinoulor not wanting to shake the dirty hand of a stranger in a “most elegant lounge suit”) in which he encounters tons of absurd characters and situations, but always circles back to his starting point, more or less (see chapter above and his request for lunch).

Here’s how Kelly puts it in her study of PAB:

a basic quest structure, thematically securing a literary filiation that is treated at once seriously and humorously, inviting us to read the text as epic and simultaneously reflecting on its differences through an ironical narratorial stance; an “eternal return” both thematically and structurally. Grabinolour sets out, weaves a narrative both horizontally and vertically as he goes and returns to the place of departure, a cyclical time structure that remains ever present, a space that constantly expands out, sure of always being in the same place. Grabinolour dominates time and space; he is man and monster in the terms with which Proust concludes his own epic narrative:

“But at least, if strength were granted me long enough to accomplish my work, I should not fail, even if the result were to make them resemble monsters, to describe men first and foremost as occupying a place, a very considerable place compared with the restricted one that is allotted to them in space, a place on the contrary immoderately prolonged—for simultaneously, like giants plunged into the years, they touch epochs that are immensely far apart, separated by the slow accretion of many, many days—in the dimension of Time.”

Another element of Grabinolour that I find completely charming and engaging, and has kept me entertained these past weeks as I reread the book a section here, a section there, letting it pull me in completely for a bit, reading it more like a collection of poems than a “novel,” is the movement. This voice is constantly in motion, rushing forward, never really pausing, continuously adding on and dragging the reader along through Grabinolour’s non-stop life.

But you can’t go and live on another planet for very long when you are a man and Grabinolour’s feet liked the earth and the asphalt for he was born on the Earth so whenever he was elsewhere he felt obliged to come back here and sometimes he found himself standing at the foot of a tree in blossom sometimes in the métro where hands with dirty fingernails . . . (“Fifteenth Chapter”)

That paradox—you have to read this slow to stick with it, to get its jokes and contours, but it’s pulling you along without any down beats or pauses—is at the heart of how I experience this book, and one of the main reasons I love it. That and the fact that it’s joyous. A joyous celebration of language, but also, Grabinolour (much like how Barbara described PAB) is the happiest man in the world. This is the opposite of those dark, cynical, humor with a knife books Dalkey is frequently associated with. It’s a firehose of fun.

I’ll end here in the same way Barbara Wright ended her preface and Debra Kelly ends her essay—with Barbara’s translation of the 31st of PAB’s pocket poems:

Nature has no full stops

Day isn’t separated from night

nor life from Death

enemies are united by their hatred

Væ soli

Why? Because he doesn’t exist

This book is not

separated

from those that will follow it

and I’m going to stop

using full stops