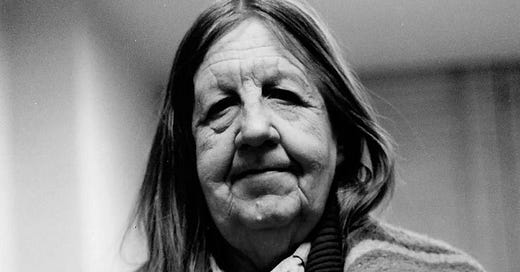

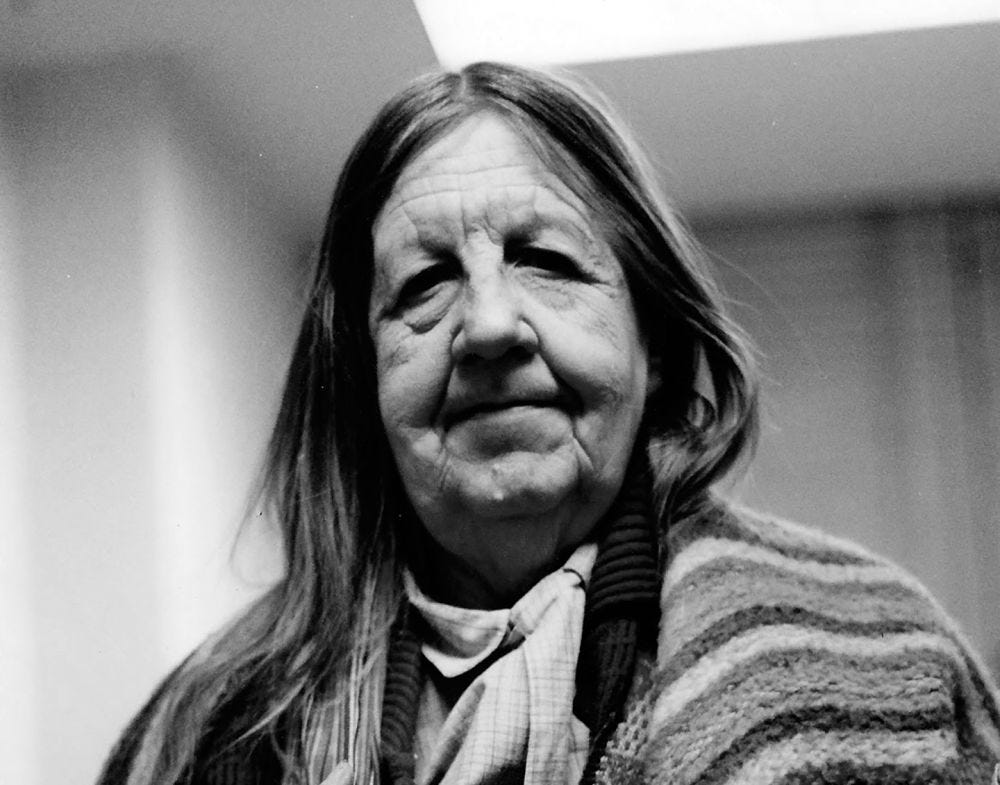

One of several interesting things that came up in last week’s podcast with Lori Feathers about Marguerite Young’s Miss MacIntosh, My Darling was the bit about how Young viewed all her works—poetry, historical writing, fiction—as part of a single book.

Here’s the exact quote, which comes from a 1988 interview with Ellen G. Friedman and Miriam Fuchs collected in Marguerite Young, Our Darling:

Q: [. . .] there were twenty years between Angel in the Forest and Miss MacIntosh, My Darling. There will be about twenty-five years between Miss MacIntosh and your forthcoming book on Eugene Debs. Do these long intervals represent major changes in the direction of your thought?

A: No. All the books I have written have been one book, from the beginning. The first poem I ever wrote, about loss, when I was five years old, expressed the themes of everything I would ever write. My early volumes of poetry, Prismatic Ground and Moderate Fable, also express a sense of loss. And Angel in the Forest, examining the nineteenth-century communities of Father George Rapp and Robert Owen’s socialist experiment in New Harmony, Indiana, is about abandoned utopias. I would say my theme has always been paradise lost, always the lost cause, the lost leader, the lost utopia.

Originally published in 1945, Angel in the Forest was Young’s first prose work to appear, and, by Young’s standards, is a rather brief book (419 breezy pages, compared to the 1,321 and 599 quite cramped pages of Miss Mac and Harp Song for a Radical) about two communities formed in New Harmony, Indiana: One that was based in religion, one in socialist ideals.

It’s a fascinating book that’s both based in historical truth and written in Young’s signature sinuous prose. For a book in which you already know the ending—spoiler, utopias fall apart—it’s nevertheless incredibly compelling, due in large part to her writing style, but also because she’s working with some wonderful material . . .

The two different societies of New Harmony—the Rappites who are dark, pragmatic, German, religious, tightly wound, and the Owenists who were more about social equality than faith—are both wildly different from one another, and yet, of a piece.

What was interesting to me as I proofed Angel for the new edition, was how much I disliked the Rappites and their draconian rules (especially the no sex one, I mean, if you’re going to start a “cult,” that’s usually not what you lead with) and their initial success. Although it makes sense that a teetotaling society would make bank by producing whisky and selling it to the American settlers. The only non-alcoholics in the area were all in New Harmony, not getting high on their own supply . . .

Anyway, when it came to the Owenites, I desperately wanted them to succeed. (If they had, I truly believe our world would look quite different—and be much saner.) And that’s one of the ways in which Young’s approach really works on its readers: She may be writing about “abandoned utopias” and “paradise lost,” but that’s only impactful if you have some hope, some belief in the possibility of utopia. The story of Eugene V. Debs is at its most heartbreaking if you thought that there was a slight, minuscule chance that he could’ve won the presidency.

This is somewhat reflected in this bit from Peter Christensen’s piece “Marguerite Young’s Angel in the Forest: A William Jamesian Perspective” from the aforementioned Marguerite Young, Our Darling in which he uses Young’s affinity for William James to look at the idea of religious experience in Angel:

Using James’s ideas on the closeness between belief and action, his stress on evaluating the beneficial results of religion, his desire to uphold rational choice in religious life, and his denunciations of exploitation, we can understand that Young is defending socialism more than utopia, and religious good works more than religious faith. James asks us to judge religion in terms of good deeds. Christ said, “By their fruits ye shall know them,” and James took this idea wholeheartedly into his philosophy of religion. So too, Young judges the Rappite community severely based on what it actuallly did to its members and the surrounding community. Like Young, James would have been more critical of the Rappites than the Owenites.

In terms of the book’s structure, I was struck by something Lori said in our conversation last week, about how Miss Mac is a book that circles and circles its subjects and topics (embodied in the bus from the opening paragraphs,1 paragraphs that also reference religion and whisky) moving less from A to B to C, instead looping around, revisiting things, progressing in an almost wave-like fashion.

That’s true of Angel in the Forest as well.

What you’ll find below is the fourth chapter of the book, which, in a rather succinct fourteen pages tells the story of the first Rappite attempt at Harmony. But the ideas she lays out here about the community, about Father George Rapp’s beliefs and proclamations come around again and again as the history of New Harmony is explored and articulated. It’s a wonderful structure, a great way to approach a topic as big and fascinating as “utopias” and social movements, and is very much in keeping with the flow of her sentences.

Enjoy!

The Children of Israel

The fire in the breast of hysterical Ann Lee, the founder of the Shaker celibate communities, had been kindled in the breast of Moses on Mt. Sinai. The fire in Father Rapp’s breast had emanated from the same original light, evidently. For both Ann Lee and Father Rapp, as for many a sultry pioneer, America was a promise, not merely of the physical conquest but of the New Jerusalem, a city above and beyond this world of shopkeepers, marriage beds, scarecrows, and other evidences of mistaken nature. Ann was the Holy Mother, as Father Rapp was the Holy Father. Both had communities of worshipful followers—but there the resemblance ends, for the marriage of true souls admits impediment. Ann built several cities, merely by shaking like a poplar tree whose leaves are silvered in wind. When she shook, her followers shook—all ceasing to consider the where, and why, and whither, and what of things. Among celibate communities, Ann’s seems the least frost-bitten, the freest from secondary aims, the most truly enthusiastic, as if no reason at all was necessary—God shaking, Ann shaking, everybody shaking. By comparison, Father Rapp’s project fails both in grandeur and mysticism, becomes the acme of prudence.

Father Rapp’s true life and its consequences may have been a drama of which he was unaware, just as he was oblivious to God’s affinity with Ann, though Ann was the receptacle of divinity, too, and sprouted most miraculously, as Father Rapp withered from the shoulders downward. His loins were girt with faith. He, with his mind fixed on an eternal purpose, could not afford to consider that his position was perhaps more average than eccentric—how many ambassadors of God there were, how many bearded patriarchs and lost tribes of Israel, how God had spoken out of every burning bush in that part of America which had been explored, how many New Jerusalems were being hatched, how many others were carelessly spoiled like ostrich eggs in Brazil. It was necessary that Father Rapp, like other leaders, feel his loneliness and his differentiation from an accursed mankind. In Germany, he was a successful farmer. Yet he would have preferred America, this land of Biblical promise, if he had had to live like the wild boar who eats roots.

Father Rapp’s cradle, Württemberg, had nurtured many clouded dreamers, many who aspired, like Faust, for infinite space, infinite power, and oranges in winter. He believed himself in league with God, however, and not with the Devil, representative of an obtrusive and detailed reality. His imagination, all the same, did not run away with him. While influenced by Jacob Böhme and Jung-Stilling—“ever the mystics farthest removed from this world”—he liked to buy cheap and sell dear. He had both his feet on the ground. He was far divergent, for example, from another under the influence of German romantic idealism, William Blake, who saw angels swinging upside down from apple trees, who saw the antinomies of heaven and hell reversed, who saw that the fly was his little brother and chief glory of God. No such raptures for Father Rapp, the strong man. Let other German schismatics from the Lutheran order seek other frontiers on eternity—such as Russian Tartary, near the Caspian Sea, where God’s snowy stars looked down, but where there were few opportunities for practical expansion. Let poets dream what they would. Father Rapp chose America first—not because he believed that God’s voice would speak out of the marsh more clearly than it had spoken out of the vineyards in Württemberg, but because the land was fierce and cheap. Father Rapp had a Bible in one hand and an ax in the other—and thus far seems the average pioneer, a far from average being, a Daniel Boone of both the infinite and finite, an adventurer. The picture, however, is deceptive. Most of the violence, unlike that of Daniel Boone or Andrew Jackson, was verbal. Father Rapp’s entire adventure, though posited on angelic beings, was the working out of an almost infallible machinery. Serious as were the perils attending this negative spirit, the conquest of the American wilderness could hardly have taken place without it.

Factually stated, Father Rapp’s saga differs from that of the average pioneer, who possessed only two hands, two feet, one head, and a perhaps limited imagination. All too frequently for most, millennium was an unorganized way of life, a hollow tree but recently vacated by gregarious hornets or the grizzly bear. All too frequently, their only real estate was the ground they were buried in, if they were buried at all. Not a few were buried in the bellies of great birds. Father Rapp had untold advantages in the age of city building. He was, from the beginning, head of a corporation whose members held gilt-edged shares in the stock of a New Jerusalem, a perhaps imaginary wealth. His fantasy was thus public-minded. He held at his command seven hundred people, an unquestioning, automatic body, greased by the soul, as it were. Seven hundred multiplied by two would make fourteen hundred hands and feet—the heads, except that they were agreed on a few fundamental assumptions, were comparatively unimportant, almost spurious. The erection of a purely negative goal made possible the avoidance of the schism. All shared, in fact, the irrationality of absolute obedience to the will of a supernatural authority—Father Rapp, who unified scattered chimeras as a theory of reality to displace reality, and out of whose spidery being was spun the web of possible human relations.

Thus at fifty, when many men think of retiring, Father Rapp was ready, in spite of his philosophy of nature’s corruption, to act as a pioneer in America—where the suppressed dream would emerge as an unhooded reality, an angel in the forest.

Father Rapp, as befitted his position of exclusive power, which had been handed down from God’s throne, came to America in advance of his people, to choose a correct site for the community of angelic beings and butchers. In January and February, 1804, he crossed the Atlantic, accompanied by his son John, who was not strong-minded, and a Mr. Haller, agent for another flock of dissenters. It was a holy mission, a renunciation of instinct for the sake of the future, where there would be no adversary among the lower elements. Gabriel’s foghorn blew in the night, doubtless. But whatever the savage wilderness surrounding him, Father Rapp would cling to a wintry concept—that nature is an inconsequential thing, a loon, but money talks.

In Germany, mapping his course by pins, Father Rapp had believed Louisiana to be the farthest removed from corrupting influences, the damned majority. That site he rejected, once he realized the utter vastness of America, a continent more terrifying than infinity, a continent crisscrossed by erroneous buffalo tracks—a maze, indeed, but neither Biblical nor geometrical. There were few, if any, cherubim riding on lions. There were many sporadic wars. Father Rapp, a peace-loving man, dutifully explored parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Ohio, a territory as yet little influenced by the aridity of rationalism. He determined on a large tract of land some twenty-five miles west of Pittsburgh, where it might be possible to insure survival of the fit by trade with the unfit. God’s agent must do business with the Devil, even in America.

Frederick Reichert, Father Rapp’s most faithful disciple, and yet most intelligent, had remained in Germany, as shepherd to the flock of gray Millenniasts until the date of their release from materially barren pastures. They were the chosen people, indeed—though few were representative of most German peasants at that time. The average German, that is, the small farmer, had turned his eyes away from the things of this earth, in expectation of a city in the sun. The new religion of rationalism, so cold, so correct, so lonely, could make little appeal to a people accustomed to a more glorious thinking, at a lower level. Where were God’s thunderbolts, and where were the showers of locusts, and where was the promise of paradise? The King of Württemberg, a rationalist, had dismissed Father Rapp when brought to trial for preaching his strange faith in the end of the world. The Rappites, like eels with eyes enlarged, seemed a harmless group intent on suicide—it was their business, he thought, infringing not at all on his, and he could afford to lose them. Their crime was not evident. He believed them to be a minority. In view of the fact that the Rappites, aberrants though they were, represented so many others or at least their aspirations, it was probably the king who was in the minority, a lost soul, a gentleman leaning on his cane like a three-legged insect, and doomed to die an insect’s death when God spoke out of the saffron clouds. At any rate, he was reasonably happy.

To Frederick, Father Rapp wrote a conservative estimate of the new land, as if it were, however, a beast which could be tamed. Using the funds of his congregation, as instructed, he had purchased five thousand wild, lavish acres. Frederick should urge no one to come, however—it was a “long and perilous journey,” without possibility of turning back, once embarked upon, the worker to be divorced from the means of production in a barbarian hemisphere, where there were more boars than people as yet. Those who could not endure privation in God’s name should drop out—what was needed most was courage to try the body and soul. They might have to sleep on the bare ground at first. They would be surrounded, as in Germany, by every peril, every temptation.

Undaunted by promised difficulties, the chosen came, sure as of their noses that they were united by a contract to which God Himself, in a loft in Germany, had been co-signer. The great drama of change was lifting them out of an otherwise obscure existence where each had been the victim of meaningless chance. Untold riches beckoned them. Now those who were despised and lonely, a minority in Germany, would be a majority in America—and Father Rapp, who had been a careful farmer, would be a king of kings. Did not such an endeavor, in God’s name, deserve the sacrifice which each must make, even the severance with memory? Surely, they would build a city of pearls, such as had been promised of old.

The ships Aurora, Atlantic, and Margaretta, having weathered many a rough-riding, fierce, implacable storm and waves ten feet high, docked in Philadelphia, that summer of 1804. They came straggling into port. Never were there more subtle pioneers discharged on rugged shores—seekers after the golden domes of Genghis Khan, and, what is more to the purpose, they would build that edifice themselves—the destruction within and the construction without. Father Rapp was down at the dock to meet them. The familiar values persisted like his beard. Nothing had changed. “And if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: it is better for thee to enter into life with one eye, rather than having two eyes to be cast into hell fire.” This group, moreover, would not taste of death, the sum total of all in nature but themselves, it was believed.

Actually, the Scriptural communism, as it was called, was not altogether miraculous, though founded on the assumption of many miracles, many escapes from the wheels of time. To transport themselves to America, the Rappite peasants had pooled their hard-earned funds, the result of sales of their property, the small farms, the wheels broken at old cisterns. In America, what uncertainties there had been in the past seemed multiplied. Organization was necessary as never before, unless the Rappites wished to perish—or sink to the position of the average pioneer, a weakling with one eye out. There was little alternative but to strengthen the bonds by which they had been united. Salt was hard to get. Besides, they were faced by the deceptive phenomena of all mortal existence and by boundless, cold immensity. At least, the wolves had been metaphorical in Germany. Father Rapp acted, therefore, as the spokesman of God and of perhaps an even harder taskmaster, blind necessity. The Rappites had to sleep at first on the bare ground, as had been promised. They were filled, however, with religious zeal. They were not tempted. They did not forget that they were related to the most sacred characters in sacred history—like Eli among the brambles, eating a raven. For God had chosen the things which are not, to bring to nought the things that are.

At the end of the first year, Harmony, Pennsylvania, had emerged—a town of sixty log houses, grist mill, barns, shops, houses of worship, sawmills, tannery, distillery. This was, however, civilization without its usual corruptions—the wilderness acting as an effective barrier between the Rappites and the mistaken world. There were street cleaners now where there had been wild pigs before, and a night watchman where the wolf had roamed, and a golden rose where the fox had slept in its hole, and a church where there had been a burning bush. No flesh should glory in the presence of God, Father Rapp said. There were ample, succulent crops. There were excellent horses. Within a few years, the Rappites could show a large surplus of agricultural and manufacturing products of all kinds. By fraternal love and internal unification, they had made a conquest over nature, this world of fugitive financiers, shopkeepers, and whoremongers. They had harnessed all the nonhuman elements, as well as human, it seems—but if they wore the bit in their mouths, they did so happily, as a matter of celestial habit.

The Rappite location was a strategic one, the point of evacuation for the West. Man, it has been said, was impelled westward in the era of discovery by no economic necessity but by the rotation of the earth eastward. The Rappites were not alone in strangeness. They seemed, if anything, the sanest group imaginable, at least by contrast with their competitors, many of whom were burdened with shrewish wives and droves of half-starved children. Their productions, when so many were unreliable, were absolutely reliable, the one certitude at a port where fantasy thrived, along with busy commerce in nonexistent townships and gunpowder. They provided shoes for energetic Americans, gun powder unalloyed by flour, and excellent whisky, enough to enflame the imagination of waning, evanescent men, poor adventurers. To the disorganized, they represented almost the climax of moral development. They were sure of a real city, of sticks and stones, when other men had nothing but an always fading prospect, a new Jerusalem under a coonskin hat. No merely average pioneer could compete with this society of homogeneous producers, united alike in life and death.

This was the German prototype of American Puritanism, compelled, as were the original founding fathers, by a sense of persecution and innate difference from the rest of mankind. Their only affiliations were with the past. They felt the greatest correspondence between, not themselves and others burning like the dry thorn in the wilderness, but themselves and God, Who had spoken out of the burning bush, themselves and the children of Israel, themselves and Saul, David, Solomon, Job, Job’s turkey, and Tobit’s dog. They were aristocratic. They converted, consciously or unconsciously, hallucination into fact and fact into hallucination, wherever they could. Their religion, while they grew fatter, was centered upon themselves, magnified unto eternity, as a body both male and female—which phantom seemed to them a virtue, not a vice, naturally. Their round red cheeks, their health, were deceptive. Purveyors of whisky, they realized no connection between themselves and crimes committed by enflamed Indians or anarchic pioneers, no connection between themselves and grizzled wife-beaters. They were self-isolated. Undoubtedly, few gave a thought to the poor Indian, who was already, like natural man, a dwindling order—though no celibate, for he had more papooses than imaginary pearls or onions on a string. After all, it is easier to comprehend eternity than the multitudinous operations of that vaster complexus, the experience of man. In honesty, it must be added that perhaps the Rappites were more interested in their cabbages than in eternity.

A bookkeeper in Pittsburgh, a future Mormon, must have observed, during the course of his business, the Rappite order—so that there is some generic relation between the polygamists and these celibates, the former springing from the latter like Minerva from the head of Jove.

In spite of dire prophecies to the contrary, with prosperity had come no decline to the individual way of life. Lo, the walls of communism were strengthened. Lo, the angelic order was not sacrificed. The Rappites renewed, by further contract, their agreement by which they had bound themselves before emigration from Germany. They would obey unquestioningly their superior officer, would give the labor of their hands, and would hold their children and their children’s children, though nonexistent now and in futurity, to do the same. They would look on morality as that which transcends this world of shopkeepers. Father Rapp, in return, was to extend such education as would tend both to their temporal welfare and eternal felicity, and to support them and their widows alike in sickness, health, and old age unto the world’s end. It had been intended that a member, withdrawing, might receive a refund in the amount of his investment, or in keeping with what his character had been. This section of the contract was abrogated, however, as comprising a tie with the mistaken world. Should anyone desire to leave this community, he must do so without reward and on his own responsibility—the dogs of hell hounding after him.

In an even profounder sense did pale Jacob triumph over his brother, red Esau. What was inconceivable to the average man happened. During a transport of religious enthusiasm, when all people seemed carried beyond the domain of their ordinary senses, for they had been considering the beauty of a ghostly erection, Father Rapp lifted his hand. Now, he said, the vow of celibacy should be taken in dead earnest—for there had been a fatal ambiguity before, with consequent embarrassment to this community and to the race of angelic beings, who see not as men see. Thus would be broken the last of all possible ties with a tired world—this vow to be as a seal upon the forehead and the lips, a sign of omniscience.

Some of the older members, according to a report which has come down, were startled. Should all men suddenly become converted to their faith in asexual angels, walls of crystal, and everlasting harmony, they realized, the earth would soon be stripped bare of people, like a dovecote from which all the doves have flown away. Still, theirs had been a lonely bypath, a way of thorns and brambles, they realized, as if they had eaten ravens like Eli. Other pioneers could be trusted to beget the usual sparrow-boned children—so that the world, even if mistaken, might go on somehow. A consoling thought, at least to a few sentimentalists. Besides, all saw the light of holiness shining in Father Rapp’s uplifted face, that unusual glitter in his eye, as if he walked surrounded by stars like empty gourds where the oriole houses, as if he were in communion with the most distant powers. The fact that all were to share in the deprival of the flesh for the sake of the spirit made the burden only easier. None should escape. They were indebted to Father Rapp, they knew. Had he not delivered them out of the mouth of the lion? Had he not brought them into a marvelous land, like Lebanon, where the eagle is perched upon the topmost branch of the cedar? There was great rejoicing, as the rafters shook. Old and young men, old and young women, many fourteen-year-olds, all leaped and shouted, and the young shouted louder than the old.

Perhaps most of these good people did not think at all, since sudden emotion is more powerful an agent than prolonged logic. There was, however, a sadly dissenting voice—a worm in the green wheat—and lo, the worm lifted up its head, for it was a cosmic dust. Father Rapp’s son John, still in the prime of his manhood, could not accept so readily the attitude of self-imposed sterility. He had his wife with him, those limbs he had already clasped, that breast like honey and mead, that immediate sense of her personal goodness, a thing more wonderful to him than thousands of angels shouting hallelujahs. She was life, John thought. Many months after the agreement on a universal celibacy, a strange thing happened—John’s wife began to swell out like the yeast of bread. It became impossible, by any subterfuge, to conceal her condition under the immense skirts and draperies of shawls. The woman was with child. Acknowledgment of secret sin was made glaringly public, by every slow movement and wandering gesture, by the eyes dilated, the breath coming short. She felt her shame, that she was Jezebel, that she was the whore of Babylon who had walked with cymbals and tinkling bells—indeed, she was the world’s disaster. People stared at her, unbelieving, for this was a greater crime than to steal a little sugar. John, far from being cautious, was triumphant openly, as if he had struggled with an angel and had come out with no part of his thigh missing. He had established, obscurely, it is true, a union between himself and the moths which are not motivated by the idea of God. He walked on a cloud, and he whistled like a mockingbird. He was happy, the poor fool. He had seen a droplet of milk on that fair breast. His wife, however, more melancholy as her time advanced, could hardly stoop to lift the turnips from the fields. The third part of the moon was already dark, and she was going down the sky with a third part of the moon. Her crime had brought its punishment. John, persisting in his ecstasy, thus differentiated himself from all the ghostly others, including his wife—he was not a tactful winner in the game of life, but boastful.

It was an embarrassing situation for the vice-regent of the Deity, the ambassador of God on earth—his own son, a father! What was more, there seemed to be no indication that John would ever desert his wife—for night after night, he went in to her. Was there to be an exception, an ignoring of the prohibition placed upon a depraved natural instinct, by which the individual withdrew himself from the residue of divine truth? Was at least one critic to stand outside the community with a cynic’s leering sneer? Men who were, after all, merely human complained of the immense injustice. They had been temperate as cabbages, and what was the result? Father Rapp determined, sadly, that the malcreant must be punished. So Abraham would have sacrificed Isaac, was it not so, had not an angel of the Lord intervened? Community must be preserved, at any cost to the finite destiny of finite man. It would be like taking down the strap from its nail on the wall—he had beaten his son before, as a training for manhood. The evil part must be removed. Nakedness, a groveling, a howling, a mute repentance as the body learns its master, self-mastery. Better to strike at evil than let evil fester! Unfortunately, this was no flogging but emasculation, and the victim died, crying like a stuck pig—somewhere in the neighborhood of the piggery.

More than one murder had taken place undiscovered in the dense American wilderness. More than one man, it is recorded, had set out on a journey from which he had not returned, and no inquiries had been made, there being a gap between the man who departed and the man who arrived, and an impossibility of communication at such extremes in time and space. More than one had been swallowed up by the wilderness—a disembodied head in a burlap sack of corn shucks, like the head of John the Baptist, a headless body weighted down by stones in a distant river. Nobody caring.

As the Rappites were isolated and their own police, it seemed that a veil might be drawn across the macabre scene. After all, as so often happens, the only eye witnesses to this murder were the murderers. Rumor got out, however, that Father Rapp had killed his only son. There was just a little trickle of blood, and then there was a dead body. It was a tale told in all the taverns, both in America and Germany—how the old man had imposed his will upon his people. Half a century later, The Atlantic Monthly carried a few hints as to what had happened. Nothing was ever said as to the fate of the widow, whether her skull and palms were cast upon the turnip fields, or what became of her. Beyond doubt, an infant daughter survived the experiment and grew to robust womanhood, with a certain twinkling laughter in her eyes.

The death of John Rapp had at least the virtue that it marked an impasse and turning point on the road of Rappite history. Now, in 1814, Father Rapp was ready to abandon Harmony in favor of a second enterprise, much like the first—to move on, like Daniel Boone, seeking elbow room. A flawless opportunity, a magnet drawing the compass—thousands of people turning toward the sunset, and among these, the Oriental despot, Father Rapp, manufacturer of whisky and illusion.

The Rappite property was sold, in short, to a man named Ziegler for $100,000, a great sacrifice, although it represented $85,000 profit over the original investment. Ziegler, by the way, had no notions as to the extinction of the human race, by mutilation or millennium. He put up FOR RENT signs everywhere and opened a puppet show, where little men danced on strings, and all their activities seemed the effect of invisible spiritual powers.

Copies of Angel in the Forest can be purchased here, or at better bookstores everywhere.

Published by Dalkey Archive Press first in 1994, then as a Dalkey Essential in 2024. All rights reserved.

“The bus-driver was whistling, perhaps in anticipation of his wife, who would be a woman with ample breasts, those of a realized maturity. It would be impossible that he did not have, from my point of view, a wife and children, indeed, a happiness such as I could not imagine to be real, even like some legend out of the golden ages. He had spoken numerous times during our journey of his old woman waiting, and he was going home.

“As if he were a Jehovah’s Witness or a member of some other peculiar religious sect, his bushy hair grew almost to his shoulders. A Witness would not perhaps drive a Grey Goose bus, even in this far country, this interior America, but his head was large, bulging, an old, archaic dome of curled sculpture, and his eyes shone with gleamings of intensified, personal vision. He drove, in fact, erratically, perhaps because of the heavy mist which all but blotted out the asphalt road, the limitation, and more than once, with the bus’s sudden lurching, I had feared that we might veer off into a ditch, that himself and his three passengers would be killed, our dismembered heads rolling in a corn field of withered corn stalks. He had whistled with each new escape, had turned and smiled back over his shoulder with a kind of serene triumph, even when the bus had brushed against the sides of a lumbering moving van with furniture piled up almost to the low sky, an upright piano, a rocking chair, a clothes’ horse, a woman’s feathered hat bobbing at the top in the grey mist like some accompanying bird.

“Was he, after all, a bachelor, perhaps even some mad Don Quixote chasing windmills, a virgin spirit, nobody—and his family life, an emanation of my over-active imagination, really, my desire for established human relationships? All along the way, he had been drinking from a whiskey bottle, quite openly, yet with many calls upon God, the angels, the archangels, angel Gabriel. All along the way, he had been singing, whistling, talking to himself, guessing what the old woman would say when she saw him, that she would certainly take his head off.”