Curtis White on the Culture Wars

Dalkey author and former board member recalls Jesse Helms's attack on FC2

After listening to the NEA podcasts from a few weeks back, Curtis White—incredible author primarily published by Dalkey Archive (Requiem, America’s Magic Mountain, Memories of My Father Watching TV) and Melville House (Transcendent: Art and Dharma in a Time of Collapse, Living in a World that Can’t Be Fixed: Reimagining Counterculture Today, We Robots: Staying Human in the Age of Big Data),1 former Dalkey Archive board president, professor at Illinois State University, and the editor of CONTEXT Magazine for many years—sent me the following essay about when he was running FC2 and accidentally provoked Jesse Helms . . . This is a very fun piece, and hopefully the first of many posts written by people other than me about publishing, particular authors (published by Dalkey Archive, or within the general aesthetic vision of the press), and more.

Tide of shit

I.

“I’m filled with the sadness that afflicted the Roman patricians of the fourth century: I feel irredeemable barbarism rising from the bowels of the earth. . . . I have always tried to live in an ivory tower, but a tide of shit is beating at its walls, threatening to undermine it.”

—Gustave Flaubert in a letter to Ivan Turgenev

Our “last hurrah” started with a phone call from Jim Sitter. Now, you have to know Sitter. At the time, he was directing CLMP (Council for Literary Magazines and Presses at the time), a service organization for not-for-profit publishers like FC2.

But Jim’s real stature at that moment came from the fact that he had single-handedly done what no one thought possible. He had gained the ear of major national foundations, most notably the Lila Wallace Foundation (from the Reader’s Digest fortune, ironically) and the Mellon Foundation.

Sitter himself was a piece of work. He looked like Tim Robbins in Altman’s The Player. He kept an immaculately trimmed beard and wore stylish but outdoorsy clothes: lots of wool and leather and always topped with a fedora. He had a look. The Sitter look. A synthesis of Hollywood and the Vermont Country Store. He also had a style. I have never known a person more measured in what he allowed himself to say. His very presence said, “I know something. Actually, I know a lot of things. These are things you’d like to know, but I’m not going to tell you, mostly because I don’t trust you not to use what I know to fuck things up.”

Jim’s style also said, “You can ask questions and I will carefully answer them, but you will never know all that you want to know. You will only know what I need you to know.” Jim was my introduction to the atmosphere that surrounds philanthropy, its “secret wisdom.” A sort of “we know you better than you know yourself; we even know what you need better than you do.” This was all condescending and insufferable, especially for book people.

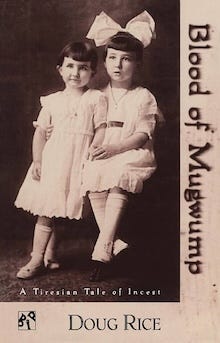

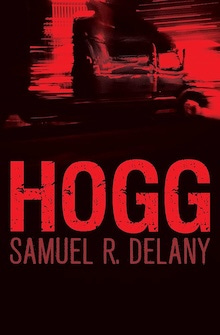

So, Jim had carefully put together this fragile alliance between CLMP, the NEA, and Big Philanthropy, all for the benefit of literary publishers, but I think he lived in the fear that we writers and publishers would mess it all up. Which of course we did. I’ve spoken elsewhere of Douglas Messerli’s failure of deference. And now here comes FC2 and its edgy books: Delany’s Hogg, Jeffrey DeShell’s S/M, Doug Rice’s Blood of Mugwump.

And then on one warm Illinois spring day in 1995, I got a call from Jim.

“How many of your books give credit for support to the NEA?”

See? No prologue, no context, no effort to allow me to understand why my answers were important before I answered. I don’t even think he took the time to say, “hi,” he just asked the question he needed an answer to.

“All of them except one,” I replied.

“Just the ones you listed in your grant application to the NEA?”

“No, all of them. I thought that the NEA would like it if . . .”

I could feel tension and maybe a groan on the other side.

He interrupted impatiently, “That was a mistake.”

“Why?”

“You shouldn’t have done that.”

“If the NEA has a problem, why haven’t I heard from Cliff?”

Cliff Becker was the director of the literature section of the NEA. He was a prince in every possible way. He was the anti-Sitter. Completely open but also smart and sympathetic. He really liked what the small presses were about, even FC2. Sadly, he died of a heart attack in 2005 at the age of 40.

Sitter replied, “Cliff can’t talk to you now. He can’t be seen as coaching your replies.”

“Our replies to what?”

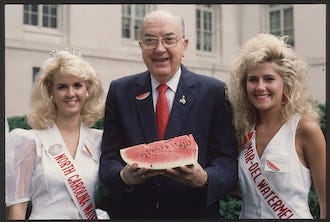

At last he came to it. “Jesse Helms in the Senate and Pete Hoekstra in the House are using your books to demand the end of the NEA, or the end of funding of literature, or a reduction in the NEA’s budget, which it seems very likely they will get. This is really going to put [President Clinton’s NEA chair] Jane [Alexander] on the spot.”

“Oh.”

“It’s just politics, it’s just a way for them to play to conservatives, to have something for their fundraising, but it’s also very dangerous.”

We were a potential liability for the NEA, and, of course, we were also a threat to the little empire Jim was creating. He was trying to make literature a philanthropic field, something corporations could feel comfortable giving money to, like opera. Naturally, he hoped to make himself indispensable to that future. And we were messing that up.

I said, “Oh,” again.

“If you are contacted by the press or by staffers to Helms or anyone else, don’t say anything.”

“Can’t we defend our . . .”

He nearly screamed, “Curt, these are not nice people. They don’t care who gets hurt. You need to be careful. I’ll let you know if we need a statement from you.” Which was his way of saying that if he needed a statement from us, he’d write it.

Saying nothing was not in my nature, but I tried to be a team player.

“Okay,” I said.

“I’ll get back to you if anything comes up.”

“All right. Thanks, Jim.”

Later that day or the next I was contacted by a reporter from the Washington Times, the Moonie paper-of-record for all things contemptible. The reporter, a woman with a very pleasant voice, asked for a comment and I thought, “She will twist anything I say to her own purposes, plus Jim told me to shut up,” so I said, “No comment.” Of course, she twisted my silence to her own purpose. She made me look bad, like I was hiding something, which I was. I was hiding the fact that the NEA didn’t trust me to talk.

I was also contacted by Christian conservative Allen Wildmon of the American Family Association. That was a surreal experience. The old cracker went on in his homespun vicious way trying to get a comment out of me, something he could put in a fundraising brochure, something to label me un-American, and, honestly, just about anything I said could have suited that purpose pretty well. I am un-American in a fundamentally patriotic way.

Anyway, it was revelatory to be in a position where I could hear the snake in Wildmon’s voice, and in the voice’s contours, and let it just fill me and allow me to know it. Thrilling, but a little scary. He came on all cornpone, and, “Heck, what do you think about all this?” Meanwhile, he’s holding a noose behind his back.

Afterwards, it occurred to me, “Wildmon. It was he and his brother Donald that went after Robert Mapplethorpe. Hey, we’re the new Mapplethorpe!”

I felt something like pride rinse down over me.

What had happened was this. In performing its ordinary if malignant due diligence, hoping to turn up some smut to hurl at the NEA, a staffer for Pete Hoekstra (R, MI) had come across one of our books. I actually had a telephone conversation with the staffer. He called, identified himself as part of Hoekstra’s office, and asked me to send him copies of all of our books giving credit to the NEA.

I asked him how they had found out about us.

“I was sitting in a coffee shop and I read a review of one of your books in the Washington Post.”

“Well, that was easy,” I thought.

During that time, in large part because of our Black Ice Books, there was no shortage of sexually edgy material just waiting for the wrong Southern Baptist to discover. At least it wasn’t going to be about Hogg. That would really have been ugly.

He continued. “I went to a bookstore, looked at the copyright page for the NEA logo, read a bit of it, and brought it back to the office.”

He was very matter-of-fact in all he said. Not scandalized, not apologetic, and not cynical. The painful part for me was that getting a prominent review in the Post was usually a cause for celebration, but now it appeared that even our successes would be used against us. I supposed that if we were going to keep NEA support, we would just have to stop being noticed.

The review was of our first Chick-Lit anthology, Chick-Lit: Post-feminist Fiction, edited by Mazza and DeShell. The reviewer was a novelist, Carolyn See, and it was not positive. In fact, as I noted on first reading, it was irresponsible. After complaining about the lack of plot in the stories, she wrote, “You never saw so many wigs and crew cuts bleached white, or so many female genitalia . . . Not many straight women here either . . . The National Endowment for the Arts funded part of this enterprise, and it is couched in words and concepts that are sure to give Jesse Helms a conniption fit.”

This open appeal to Helms in a Washington newspaper, for God’s sake, may be the worst thing I have ever known a writer to do to fellow writers. The incredible irony is that in the 1950s Ms. See made a living testifying for the defense in pornography trials of books like Lust Thy Friends and Neighbors. Even crazier, her own father wrote seventy-three hardcore pornography novels, as she attests in her memoir of the period, Blue Money.

But she was shocked, just shocked, at Chick-Lit.

II.

“You smile with pomp & rigor: you talk of benevolence & virtue;

I act with benevolence & Virtue & get murder’d time after time.”

—William Blake, Jerusalem

And then on September 17, 1995, Jesse Helms took to the Senate floor waving Doug Rice’s Blood of Mugwump—an omni-gendered outrage fit to make William Burroughs blush—over his head and complaining about how it had traumatized the impressionable young people on his staff. He was arguing for a bill sponsored by John Ashcroft to defund the NEA. Waving the book as if it were McCarthy’s list of commies in the State Department, he said, “This book called Blood of Mug . . . Mugwump . . . I’ve never heard of the author . . . is repugnant to the values . . .” and so on.

Jesse Helms’s death in 2008 was the closest he ever came to honesty. There’s an inevitable frankness about dying. The ugly truth takes off its mask. Even so, he probably raised a desperate “question of personal privilege” about it, thus putting himself in the merciful hands of the great parliamentarian in the sky, who ruled against him, obviously. A perplexed Helms discovered himself to be, at last, just another ghost, immortally “roamin’ in the gloamin’” of this Bardo we call Life on Earth.

I’d have thought it was all good fun if Sitter and the NEA hadn’t been freaking out. Naturally, he made no effort to defend us or our books. They set us adrift.

It would have been nice to live in a world where Jane Alexander could sit before congress and say, “Senator Helms, do you Republicans read? Like, at all? Have you read, for example, Greek mythology? Are you familiar with the story of Procne and Philomela? After Procne’s husband Tereus rapes her sister Philomela and cuts out her tongue so she can’t accuse him, Procne chops Tereus’s children up, cooks them in a stew, and feeds them to him. Well, Mugwump retells that story, among others. Is that still ‘repugnant to your values’? Then, Western civilization is repugnant to your values. And that, frankly, is as it should be, given what you are.”

But, as you know, we don’t live in that world. Jane Alexander is a Hollywood actress who Clinton named NEA chair because he thought she’d be too pretty for all those Republican pricks to be mean to, but I guess southern gallantry really is dead.

In the end, the situation was this: the NEA can fund art as long as it doesn’t fund art. Or it can fund art as long as nobody finds out about it. Jane Alexander would have been better off if she’d told Cliff to give us the money in hundred-dollar bills in a plain manila envelope. I’ll tell you this, although we played along with the team, shut up and let them handle it, we did not get an NEA grant the next year. FC2 did not receive an NEA in the following thirty years. We could have listed Hamlet on our application and they would have refused it.

So, let me say now what I would like to have said then. In the end, the NEA is a bureaucracy assigned the task of managing art, not aiding it. Or put it this way: it does not provide support to art that offends its masters. Indifferent to what offends the bosses, publishers like FC2 go about their business of re-energizing the idea that narrative art can still matter as social and, in its own way, spiritual antagonist.

Spiritual antagonist? Yes. Because when narrative art is not merely a confirmation of dominant ideology, when it is not just another domestic drama that does nothing more than confirm the world we already know, the work of art is an act of refusal. A refusal to live in a dead world, the boss’s world, money’s world. Art is the one place where life insists on living. And that is spiritual.

Oh, and Hoekstra’s staffer? When he asked me to send him all of our books, I said, “Go buy your own copies. We could use the sales.”

More of the same shit

I was starting to get pissed off. Pissed off at the reptiles in office, pissed off at the way we were being misrepresented and abandoned by Sitter and the NEA, but also pissed off at my own naïveté.

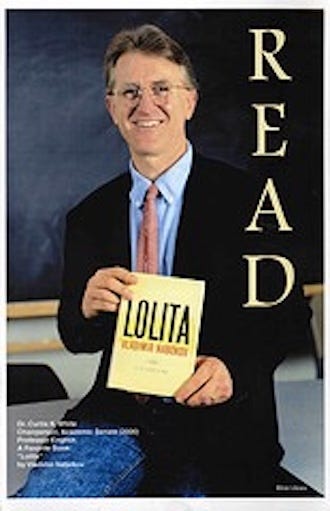

My naïveté had nearer repercussions as well. The local newspaper, the Bloomington-Normal Pantagraph, asked to interview me about the controversy. Now, they had done stories on me and our publication activities several times in the past. I trusted them to treat me as a known and respected member of the community. So, I tried to explain myself and the press, and then posed for a photograph holding one of our books in my hand with a big goofy smile on my face. It was as if I were stupidly proud about something, or just stupid. And they did not treat me as a member of the community. They took advantage of my predicament in order to have “a national controversy in Normal!”

It happened that I had a former student, Randy Gleason, who was a reporter for the Pantagraph. I told him that I was disappointed in the article. I said that it called into question the legitimacy of my life’s work. I said I was particularly annoyed by the headline, “Art or Pornography?” which hung over my photograph.

He said, “Curt, you have no idea how much worse it would have been if I hadn’t been there. The headline they wanted to use was ‘Is This Man a Pornographer?’ I threw a fit. I said you were a philosopher, so they went with this headline.”

Actually, what Randy had done made me feel a pleasant, warm gratitude. His gesture was the first time anyone outside FC2 had been honest and loyal. Plus, I like it when someone mistakes me for a philosopher.

The pathetic coda on all this took place a month or so after the Helms tirade. My local congressman, acknowledged as the stupidest man in Congress by his peers, Thomas Ewing, informed the press that he would be making a personal visit to my university president to discuss the NEA controversy and my role in it. I didn’t think I could be fired on the request of a congressman, and the administration had a strong record of defending the arts against censorship, so I wasn’t worried. Much. Ewing was informed that it was a university matter and no concern of his. (Man, has that idea gone away.) Then, they talked about the weather, corn, and the men’s basketball team for fifteen minutes, just to give the impression of a “frank exchange of ideas.”

Yes, I had caused some trouble that I’m sure the administration could have done without, but what did they expect? If you let working-class, hippy artist radicals into the ivory tower, there’s gonna be some gobsmacking at one point or another. I was a professor, one of the privileged, but I did not know the “rules of the game,” in Jean Renoir’s 1939 movie of that name, and I had no intention of learning them. I give the Woke professoriate full credit for the same.

A coda to my coda and I’m done: I was teaching an introductory literature class while all this was going on and (for not very good reasons) I launched into a rant against conservatives, naming Tom Ewing. A student raised her hand. “Before you go on, I think you should know,” she said, “that I’m Thomas Ewing’s daughter.” I was horrified. She continued, “It’s okay. We don’t agree about a lot of things. I just thought you should know.”

I was chair of the Academic Senate for three years and they asked me to take part in a “community reads” series. While everyone else chose children’s books and easy reading, I chose Nabokov’s Lolita. Yes, I was being difficult. I happily break the “rules of the game.”

Here is Curtis’s complete bibliography (in order of publication):

Heretical Songs

Metaphysics in the Midwest

Anarcho-Hindu

Monstrous Possibility: An Invitation to Literary Politics

Memories of My Father Watching TV

The Middle Mind: Why Americans Don't Think for Themselves

The Spirit of Disobedience: Resisting the Charms of Fake Politics, Mindless Consumption, and the Culture of Total Work

The Barbaric Heart: Faith, Money, and the Crisis of Nature

The Science Delusion: Asking the Big Questions in a Culture of Easy Answers

We Robots: Staying Human in the Age of Big Data

Living in a World that Can’t Be Fixed: Reimagining Counterculture Today

When the NEA recently canceled a bunch of grants to theatre companies, I upset some of my friends by pointing out that we shouldn't have applied for grants in the first place. "But without that grant money, we might lose our jobs," was a commonly expressed fear. And I sympathize; precarity sucks. However. If you are really a true antiracist, antifascist, anti-USA artist, then how can you take blood money from the empire? Can you imagine Thomas Mann or Walter Benjamin applying for a grant from the Nazi regime?

This was great read. It would be depressing if literally everything wasn't so much worse now.