How Does This Get Read?

Bottom's Dream, the Arno Schmidt Project, and Philanthropy

I reflected on the subject of my spare-time literary activities. One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with. A good book may have three openings entirely dissimilar and inter-related only in the prescience of the author, or for that matter one hundred times as many endings.

—Flann O’Brien, At Swim-Two-Birds

The Arno Schmidt Project

In 1994, Dalkey Archive unveiled a rather ambitious publishing scheme: To bring out four volumes of Arno Schmidt’s work—in hardcover and paperback—and to develop a readership for one of Germany’s most “difficult” authors through a concerted effort of getting Schmidt taught in the academy via special conferences, symposia, the development and publication of critical materials, and other marketing activities.

The series, entitled the “Collected Early Fiction 1949-1964,” launched with Collected Novellas and includes Nobodaddy’s Children, Collected Stories, and Two Novels: The Stony Heart and B/Moondocks. All of these were translated by John E. Woods, who was, at the time (and arguably even now) the most decorated and influential German translator of our times. (More on him in a bit.)

Like clockwork, these four volumes came out in 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1997. Not sure if there were any academic conferences, although the best I can find is this bit from Stefan Hopper’s review of Michael Orthofer’s book on Schmidt in The German Quarterly:

While Schmidt is more or less regarded as a canonical author in his home country, he remains virtually unknown in the English-speaking world. His works are rarely taught at North American universities, only a small number of studies exist, and even the presenters at two Arno Schmidt conferences at Portland State University in Oregon were mostly flown in from Germany. To be sure, Schmidt has found even fewer readers outside academia.

Academics commenting on readership is the very definition of the kettle calling the pot black, and, to be honest, not exactly accurate. It’s no secret that literature doesn’t sell all that well in the U.S., that literature in translation sells worse, and that experimental authors in translation are lucky to crack 1,000 net copies sold. (Every volume in this series broke that number.)

To give you a sense of who Schmidt was as a writer—and without using the “Joyce of the Finnegans Wake persuasion—here’s the opening of Scenes from the Life of a Faun (part of Nobodaddy’s Children), a relatively popular work of his:

Thou shalt not point thy finger at the stars; nor write in the snow; but when it thunders touch the earth : so I sent a tapering hand upward, with beknitted finger drew the slivered <K> in the silver scurf beside me, (no thunderstorm in progress at the the moment, otherwise I’d have come up with something !) (In my briefcase the wax paper rustles).

The moon’s bald Mongol skull shoved closer to me. (The sole value of discussions is : that good ideas occur to you afterward). [. . .]

Not a continuum, not a continuum ! : that’s how my life runs, how my memories run (like a spasm-shaken man watching a thunderstorm in the night) :

Flash : a naked house in the development bares its teeth amid poison-green shrubbery : night.

Flash : white visages are gaping, tongues tatting, fingers teething : night.

Although all four of these volumes were reasonably successful—even, or especially, by Dalkey standards—nothing happened with Schmidt for twenty years. Then Bottom’s Dream landed with a resounding THUD.

The Object Itself

Bottom’s Dream is 10.75 inches wide, 14 inches tall, and 3.5 inches thick. It weights 12.95 pounds and is a mere 1,496 pages. It’s as long as Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, but is a single volume. It has 14 ratings on Amazon.com. 62% are 5-stars, 27% are 2- or 1-star. Of the people who gave it five stars, I personally know several.

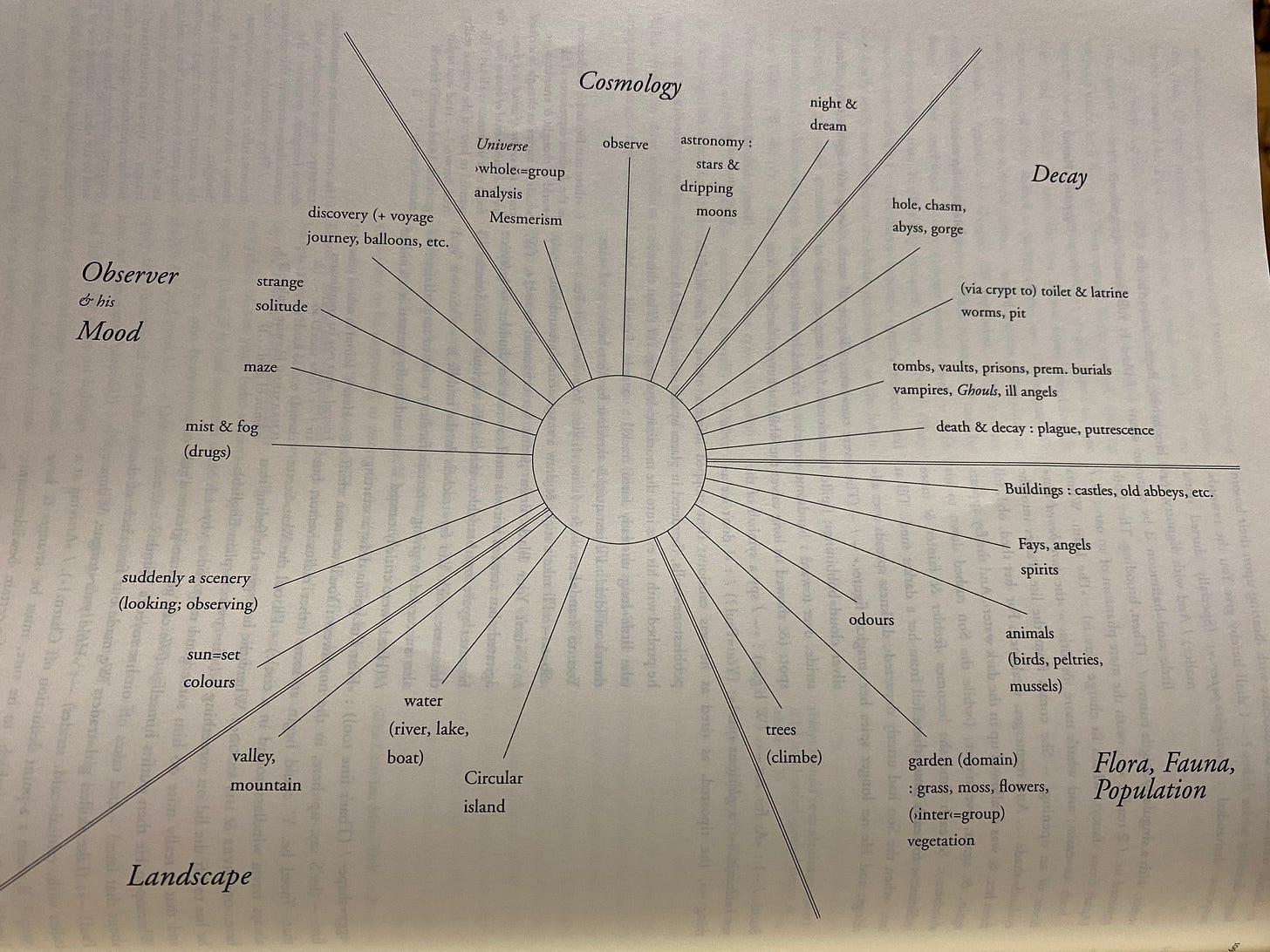

Here is every single page.

Difficulty, or “Difficulty”?

Dalkey Archive Press: Arno Schmidt’s prose is layered, but never to the point of complication. It is concise, sharp, fragmented at times, but deliciously human, intimate and real. How do you think younger audiences will read him?

John E. Woods: Arno Schmidt has always attracted a younger readership, and most of those readers stick with him. He is a fearless author who does what he knows he must do and thumbs his nose at taboos. That alone I think is what makes him a voice that younger, serious readers connect with. He is also at times foolishly opinionated, unnecessarily arcane, and always a man of his own time and place, all of which can set up barriers for those same readers. Yet even what may seem his “faults” lead to revelations about himself, and more than any other writer I know, he is willing to risk relentless self-exploration. His words are who he is. That kind of literary honesty resonates with younger readers and it’s an addiction that can last a lifetime.

On its surface, this seems like a really bold statement. Schmidt is a voice that younger, serious readers connect with?!?! That might have been true in Germany in the 1970s, before J. K. Rowling adolescentified the reading experience for millions of people—young and old alike.

Although John O’Brien would always bristle at the mention of Dalkey Archive publishing “difficult” literature (paraphrasing here, but he attributed that term to lazy academics, and average readers who hadn’t had their reading skills corrupted by the system could enjoy any and all Dalkey titles), he didn’t shy away from titles that threw down challenges. Next episode we’ll look into some of the more “reader-friendly” (and female) Dalkey titles, but this is a press that has done Christine Brooke-Rose, Gertrude Stein, Marguerite Young, Gilbert Sorrentino, William H. Gass, and many others who would likely flunk out of today’s MFA programs. Complicated literature is not something to be afraid of.

(Random Memory: When I started at Dalkey, the main ad slogan was “Read Different.” It was an homage, or theft?, of an Apple slogan, but it did sum up the late-1990s and early-2000s. As Dave Eggers and McSweeney’s ascended, Dalkey Archive was there, keeping them honest about just how “avant” their books were.)

What does it mean for a book to be “difficult”? Usually this is shorthand for one of two things, either the author/publisher’s attempt to affirm the “lasting literary nature” of the book in question or, its exact opposite, a variety of shade book critics use to deplete a book’s potential audience.

I’m 100% biased in my assessment of “difficult” books, as someone who has always been drawn to the fringes, to the unpopular but unique. That said, maybe “difficult” books are just ones that require more attention. Books that “teach you how to read them” is a common cliche among the so-called literati, but there is that kernel of truth: If you pay attention and let go of your preconceived expectations, then so many more works are comprehensible and enjoyable. And the world is a better place if we have both Bridgerton and Bottom’s Dream in it, appealing to audiences that very rarely overlap, but are very passionate about the joy they receive from these respective properties.

Maybe books aren’t actually difficult; difficulty is a mix of perception, expectation, and patience.

How Did This Get Made?

Let’s pause before talking about the actual experience of reading Bottom’s Dream. You’ve seen it, you’ve heard of its legend. All philosophizing aside, there isn’t a book in the world that weighs 14 lbs that isn’t intimidating.

Before I get into this next section, I want to make a disclaimer: I don’t know ANY of the specifics regarding the publication of Bottom’s Dream. But, based on structural, anecdotal, and experiential knowledge, I think I can sketch out some behind-the-scene numbers that are at least semi-related to reality.

What I do know: This hardcover was published in a folio size, with a slipcase, and wrapped in plastic. Every element in that sentence is $$$$. If a mass market book (pocket sized, printed on shitty paper, made to be disposable) is one end of the spectrum, this is the other.

Let’s start with the publishing costs that we can maybe delineate.

Printing. Given the life-to-date sales of the book, I’m pretty sure that 2,500 copies were printed. I know they were printed in Germany (it says so on the copyright page), but since I don’t have any sense of the German printing market, I’m stuck using the resources I have available to me. Bookmobile not only can’t print a book of these dimensions, it won’t give me a quote on anything even close to this object. I’m pretty sure I broke the “quote generator” querying it so many times. “Your printing price is $undefined” is such a bummer. In fact, I’m probably on some weirdo list now given the fact I’ve run at least 25 different queries.

The best I could get is that 2,500 copies of a 500-page 6” x 9” hardcover would cost $21,675 PLUS shipping. For the sake of argument, let’s assume the printing of this book cost $50,000. That seems more than reasonable.

Translation. Hoo-boy. How do you even price this? Not all translations should be priced equally, no matter what publishers and translators say. (The infamous Dalkey translation payment scheme is best left for a weekend when I’m feeling more brash and invincible.) Let’s say that John E. Woods, who won MULTIPLE awards, including for his Thomas Mann translations which are the gold standard (he’s no Pevear and Volokhonsky), earned $150/1000 words. That’s highway robbery! He also, at least according to an allusion in the afterword, learned InDesign to be able to translate this in columns. Aesthetic and neurological arguments about “difficulty” aside, Woods wasn’t translating some pulp nonsense, but a book with infinite puns and typographical typhoons. The book is, at minimum, 1,000,000 words long. So, putting aside the fact he worked on this for “some six year (spread over twelve),” his minimum payment should be $150,000.

Here are some of the other costs that would go into the production of this book, but which I’m going to ignore because I’ll make my point either way: Design, Rent, Marketing, Proofreading, Operating. Can you imagine being hired to lay out this book?

All those costs—which accrue far faster than you think—this book cost $200,000 minimum, just to produce.

Dalkey sold almost 2,000 copies of this book. A number that likely under-represents the overall demand for it. There’s every chance that the hardcover could’ve sold 3,500, with another 1,500+ in paperback. (I’m giving a lot of weight to the idea that consumers would’ve wanted to own the hardcover because of its beauty as an object. See one in real life and you’ll want to own it.)

If Dalkey sold 2,000 copies at $70 a piece (so cheap!), they would have grossed $140,000. After taking away the discount given to booksellers AND the amount given to Ingram to distribute this, Dalkey likely earned around $50,000 on one of the most unique works of literature to ever be written. That’s a loss of more than $150,000.

The Arno Schmidt Experience

When Bottom’s Dream came out, Nathan Gaddis started a Goodreads group to read and discuss the book in its entirely. At the same time, a number of translation-minded folks were pissed that the book didn’t even make the Best Translated Book Award longlist. (Next time we’re in a bar, I’ll expound on this story, but the combination of not getting review copies plus being overwhelmed by the nature of the novel turned off a lot of judges. It’s a complicated situation when you put it in the context of “awards” and, especially, “best.”)

The group petered out.

He was gracious enough to answer a few questions about his experience.

Chad W. Post: How did you first hear about BD? What’s your history with Arno Schmidt?

Nathan Gaddis: A few years before the announcement of the Woods translation a few of us on Goodreads were tossing around the titles of some big extravagant novels. The weird ones one might say. And a student in Europe piped up with, Have you heard of Zettel's Traum. I took a quick look around and was immediately blown away. THIS was the kind of thing I was looking for. Being the Completionist I am I immediately gathered up everything I could find from Schmidt in English, which was mostly the four Dalkey volumes (which I picked up at The Village Bookshop the night George Saunders was giving a reading to a very packed house) and the two volumes of radio addresses. There's even an Arno Schmidt archive here in town so I took a pilgrimage and browsed a while in his huge volumes, including the typescript edition of ZT.

CWP: What was your impetus in putting together a reading group? What benefits did you find from reading it together in that way?

NG: As with the other groups I moderate on Goodreads, it's mostly just a clearinghouse for all things Schmidt. More of a way of organizing interest in his work than a proper reading group. It's really rather difficult to get people all on the same page reading=wise—kind of like herding cats; so the sense of a “reading group” never really came together. But still it's a pleasure to have so many readers of Schmidt all kind of hanging out in the same place. We even had a German reader who was reading both the English and the German texts side=by=side.

CWP: How much time do you think you spent reading it?

NG: To be upfront here, it's been almost four(!) years since I've been in Bottom's Dream. My last update reads :: “10 pages/day. Pretty gud.” That was probably let's say just two hours of reading. So doing the math :: a lot of time. But it's a nice slow leisurely reading. A rambling read. I'm bookmarked at page 710.

CWP: Can you try and describe the levels of comprehension you achieved as you read the book?

NG: I would say actually fairly high. 80-90%? to put a number on it. It's not exactly difficult reading line=by=line. Stepping back and piecing everything together perhaps gets a little more difficult ; it's a lot of material to synthesize. But for me the pleasure is at the word level, at the sentence level. I don't really try to overexert myself with analysis and comprehending “everything.” Some things I knowingly just let slip by. It's nowhere near as difficult as say Finnegans Wake or Julian Rios' LARVA: Midsummer Night's Babel. [Ed Note: Another Dalkey title.] But it does take some preparation ;; familiarity with Joyce=level literature and some acquaintance with Schmidt's project in general are helpful going into BD.

CWP: What’s your favorite line?

NG: Embarrassed to say I don't have one. Not off the top of my head. But for Schmidt, the phrase that stays in my head is :: “My life ? ! : is not a continuum !” from Scenes from the Life of a Faun.

CWP: How did reading this impact other books you’ve read since?

NG: As with reading Finnegans Wake, it's left a lot of books wanting. I keep looking for that next novel that allows itself the level of freedom that this kind of writing experiences. I think there is also a certain freedom from the tyranny of “total comprehension” that this kind of text grants the reader. One recent example I've read, and it falls into that kind of Dream novel as well, is Mangled Hands by Johnny Stanton (new edition forthcoming from Tough Poets Press (!)).

CWP: What made you stop?

NG: Hmm, yes. It's been four years hasn't it? I stopped largely due to the physical situation its reading demands. My set=up is a table top lectern placed on a coffee table with a walnut Adirondack chair. Kind of scootched forward, bent over the text. Trying to get adequate lighting. Mostly I like to read outdoors. So maybe this summer I can move it all out to the patio? I do regret leaving off for so long and am eager to find the time and head=space to get back to it (it does require copious amounts of headspace). So, no, definitely no aspect of the interior of the novel led me to stopping ; it's just such a damn demanding physical object!

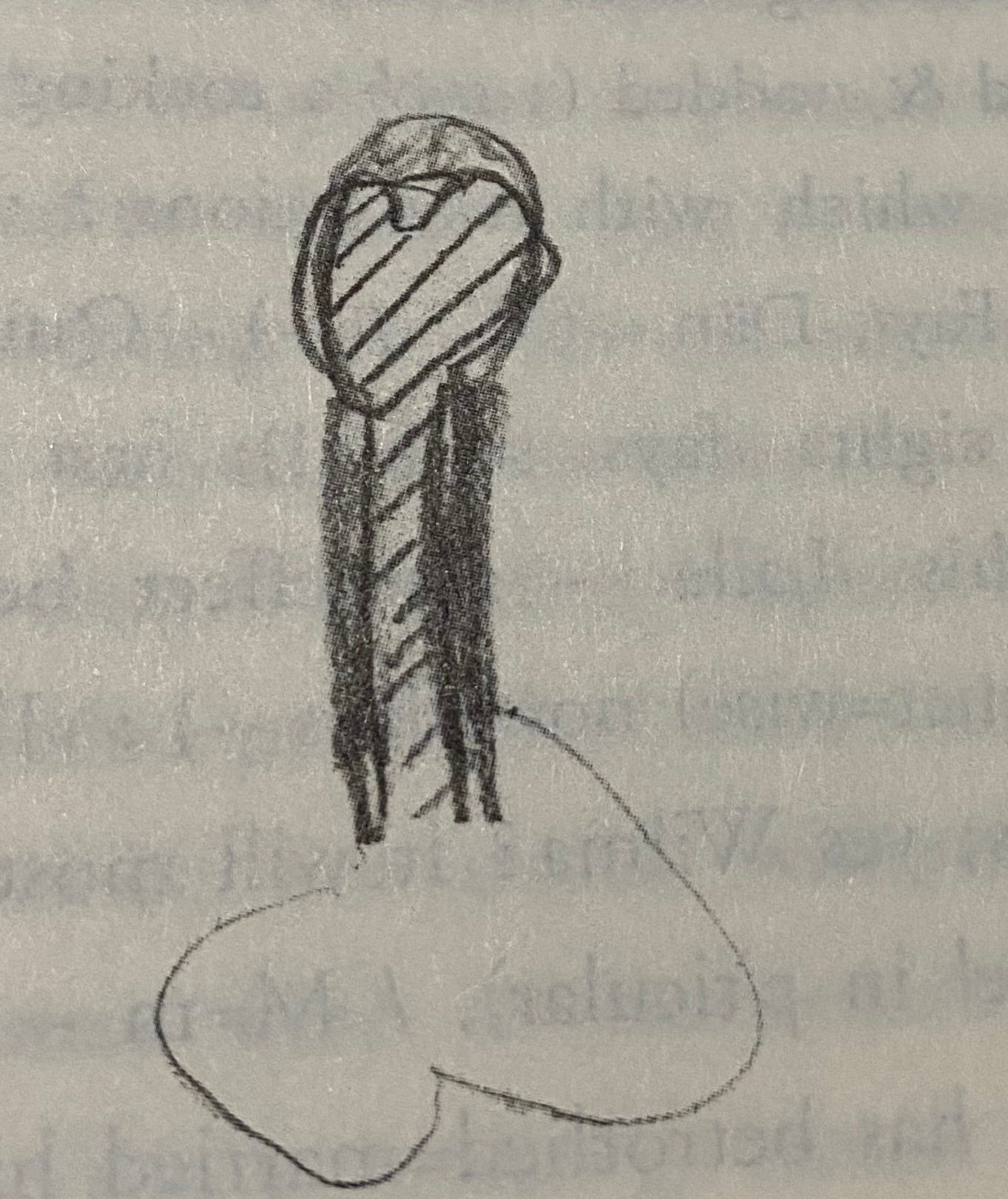

Nothing has made me want to read this book more than Nathan’s responses (not as challenging at Finnegans Wake!) and the process of flipping through every page, picking up on lots of phallus jokes.

The Philanthropist

Jan Philipp Reemtsma founded the Arno-Schmidt-Stiftung (or Foundation) in 1981—the same year that John launched the Review of Contemporary Fiction. And with a similar goal: To promote and protect the works of Arno Schmidt.

Reemtsma is also the founder of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, which is a private foundation sponsoring research (obviously) into history and social sciences.

I don’t know the specifics of Reemtsma’s fortune, nor should it really matter since I would rather evaluate him on his actions than anything else, but he supposedly inherited a tobacco fortune worth over $300 million. (Quick ethics check: If you had won $750 million in the Mega Millions drawing last Friday, which artists and strains of scholarship would you have spent your money on?)

He has also read the German audiobook of some of Arno Schmidt’s stories, and written a few books of his own, including More Than a Champion: The Style of Muhammad Ali and In the Cellar.

For the few of you still reading, here’s the payoff.

The Possibly Apocryphal Anecdote

It’s been said a million times, but I started at Dalkey Archive in July 2000. The Arno Schmidt project was well over. He was barely talked about in the office—not because he wasn’t an important Dalkey author, but because there was nothing else to do for him: there was no more money.

Even if those four volumes did “well” (average sales of almost 2,500), and only cost a tenth as much as Bottom’s Dream, the only way to publish literature that’s both shunned by the university (with its notoriously uptight literature departments, so distant from reality) and rarely going to show up on an indie bookstore newsletter is through additional funding. Say, for example, that the Arno Schmidt Foundation paid John E. Woods to take twelve years to translate Bottom’s Dream AND paid the printing costs. Dalkey could, probably, break even even if you include the expenses of running an office, marketing Schmidt, getting screwed by discounts and distributor fees, and showing face at as many book conventions as possible, even if the sales rewards of said conferences all trickle up to the Big Five.

In March 1996, Jan Philipp Reemtsma was kidnapped.

He was held captive for 33 days, and his kidnappers received the largest ransom payment ever at that time. Thirty million Deutschmarks, ten million of which were in Swiss currency. All in 1000 DM bills.

All of this money has been laundered in Eastern Europe and Latin America.

That all really happened; here’s the part I remember, maybe fallaciously:

In 1996, when Dalkey was doing the third—and preparing the fourth—volume of their series, John faxed Reemtsma for money. Several times. With no response. The series was funded by the Stiftung, obviously, and to make each stage a reality, John would ask for the next bit of funding. Just like he did while Jan Philipp was chained in a cellar, terrified and hoping that his wife and friends would finally make the $30 million DM (equivalent to $20 million U.S. dollars at the time) handoff so that he would be set free. That he would live.

In the Cellar

His book about these experiences is harrowing, filled with an emotional distance that only reinforces the core trauma (see the mix of third-person and first-person narration below), and contains a passage that is very applicable to our/my COVID times:

Several weeks after his release, I was still having a frequent sensation that I was suddenly disappearing again, losing contact with the world around me. And sometimes the sensation was purely physical, only disturbing the surface of the body. I felt I would lose my mind if his/my body was not touched, taken in someone’s arms, held tight, as if an external strength were required to save me from my own disappearance, and I needed to feel this strength against and on my body. It is also valid in this context that an internal reaction requires external criteria.

Reemtsma relates his kidnapping in three sections: the facts from the view of the outside world, his experience in the cellar, the aftermath. The writing is controlled, precise, and as much as he tries to keep his intellectualism separate from the emotions present in being seized outside your door, of having your wife discover a kidnapping note underneath a live grenade, he circles around a depth of fear and trauma that far exceeds the horrors of 2020. And he comes off as the least shitty millionaire ever.

The End

What I heard was that John kept faxing and faxing, asking for funding for the Arno Schmidt Project, and got wicked paranoid that he was being intentionally ignored. This brought out Demon John (we’ll get into that two episodes from now) and he assumed that Reemstma was blowing him off. No. Fucking him over. There’s no one who wasn’t one bad communication from falling into John’s “intentionally fucking me over” camp. As an employee, if you didn’t want to go to a Saturday dinner at John’s house, he would likely put you in that category, label you as “disruptive,” and tell other employees you were “on your way out.” Funders got no benefits of doubt.

Until one day, Curtis White read a newspaper article about Reemstma and how his ransom was the largest in European history. “Isn’t this the guy you keep faxing?”

The Artist

If you want to know more about Arno Schmidt, please please please buy Michael Orthofer’s Arno Schmidt: A Centennial Colloquy.

All images in this newsletter are from Bottom’s Dream. And you can purchase all of the books mentioned here via Dalkey Archive’s Bookshop.org page.

Is it bad form to say I own *two* copies of this monster?