The Fall Dalkey Essentials Are All About Excess

A preview post that's definitely not a preview post.

When I first sat down to write this, I planned on banging out a quick and light preview post, a listicle featuring the next “season” of Dalkey Essentials so that everyone knew what was coming, and so that Deep Vellum’s marketing team has a clearer sense of why I’ve dubbed these books Essentials, and how I see them fitting together. I could group them all under a cute rubric—in this case, “Excess,” which, if you read what follows, needs no further explanation—and write something pithy about each title, aiming for a tone hovering between “remember this book?” vibes and “hey, if this author is new to you, you have to read them.” You know, a preorder encouraging listicle.

But that felt a little boring.

If I were unveiling new information—like I will, soon, with regard to the Essentials coming out next summer—it would be one thing, but the next “season” of Essentials is already listed on the Master Dalkey Title List from April, and referenced in this PDF version of Deep Vellum’s catalog, with each of the titles grouped into one of these four color-coded Bookshop lists. The information is out there, everyone reading this is capable of reading jacket copy—what could a preview possibly add?

Personally, I don’t really ever read “preview” posts. I skim them—frequently—and, with reckless abandon, order up anything that catches my eye. Books that then arrive months (and sometimes months and months and months) later, usually after I’ve totally forgotten that the book was even coming out. I don’t ever read the descriptions or blurbs and only read jacket copy to goof on it. Just give me a book with nothing but the title, author, and translator, and I’m good to go.

It’s the same for movies. I hate trailers and on two separate occasions hid my head and covered my ears to avoid seeing the one for One Battle After Another. Generally speaking, I want to go into most of my artistic experiences as close to blind as possible. I prefer the surprise.

So writing a preview post feels weird.

It’s especially weird in this instance, since the six books coming out in the “Fall 2025–Winter 2026” season1 are a mix of Essentials that weren’t all supposed to come out at this time or in this particular order. Each set of six titles that I select for a given publishing season are chosen for reasons that, in my mind, at that moment in time, totally make sense—especially when laid out in a given sequence. Being the dork that I am, I get way way into the idea of reading things in a certain order, as if the rollout of the Essentials were a survey course on a particular thread of the Dalkey catalog.

This approach of mine may or may not be successful from either an editorial or marketing perspective, but it is a view of publishing and criticism and reader engagement that really appeals to me—both as a series editor, and in terms of how to organize and shape this Substack. Especially this Substack. It’s here that I want to move through and investigate parts of the Dalkey backlist with a certain intellectual drift, putting my own self-edification on display and, if any of this “works,” providing a lot of on-ramps to this gigantic, sprawling set of titles that constitute Dalkey Archive Press’s aesthetosphere. With the Dalkey Essentials serving as the backbone, no, better metaphor, as a superhighway connecting all those on-ramps, helping to metaphysically map the DAP backlist . . .

So anyway. Here’s my version of a preview post covering the next four Dalkey Archive Essentials, which can all be found and preordered here.

The Franchiser by Stanley Elkin, Introductions by Adam Levin & William H. Gass

Elkin is an author who definitely needs an on-ramp for the uninitiated. A “writer’s writer” with ten novels, four collections of stories and novellas, a book of essays, and, arguably, no single masterpiece. Not that Elkin’s books aren’t masterpieces, it’s just that there are so many great ones that—kind of like Philip K. Dick—it can be hard to know where to start.

Although, c’mon, The Franchiser is the only real place to start, right? Both William H. Gass and Adam Levin think so! (And so do I.)

Speaking of Adam, his introduction is a brilliant addition to this book, and I hope to run it and/or have him on the podcast to talk about Elkin’s influence in the near future. (Maybe this post is a preview, not of the upcoming titles, but of future posts?)

I am planning out an “Elkin Power Ranking” post, just to review all of his Dalkey books—half of which I’ve read over the past year in order to get them back into print—and try to gin up a debate about which belongs on top: The Franchiser, The Magic Kingdom, George Mills, The Living End, Boswell, The Dick Gibson Show . . . Honestly, an argument can be made for any one of these.

Elkin is the prototypical “voice driven” Dalkey author. His books are slangy, chatty. His characters never shut up, his lists never end. He’s written a whole book about a pioneer in talk radio, a man who is essentially a disembodied voice, reinventing himself over and over with every new voice he creates. The patter is constant, the jokes unrelenting, the mania always aquiver.

The Franchiser focuses on Ben Flesh, the eponymous franchiser, who, having inherited the “prime rate” from his godfather, goes forth and populates America with Mister Softees and Fred Astaire Dance Studios. But [record scratch] his MS is getting worse and he’s facing his own mortality, the end of his run, of his expansion, of the situation he was godfathered into.

It’s the speech from the godfather at the beginning of the book—on his deathbed, giving his last wishes to Ben—that makes this Elkin title my personal favorite. Actually, if I’m being honest, it’s probably this single paragraph that tips it for me:

“Ben, everything there is is against your being here! Think of get-togethers, family stuff, golden anniversaries in rented halls, fire regulations celebrated more in the breach than the observance, the baked Alaska up in flames, everybody wiped out—all the cousins in from the coast. Wiped out. Rare, yes—who says not?—certainly rare, but it could happen, has happened. And once is enough if you’ve been invited. All the people picked off by plagues and folks eaten by the earthquakes and drowned in the tidal waves, all the people already dead that you might have been or who might have begat the girl who married the guy who fathered the fellow who might have been your ancestor—all the showers of sperm that dried on his Kleenex or spilled on his sheets or fell on the ground or dirtied his hands when he jerked off or came in his p.j.’s or no, maybe he was actually screwing and the spermatozoon had your number written on it and it was lost at sea because that’s what happens, you see—there’s low motility and torn tails—that’s what happens to all but a handful out of all the googols and gallons of come, more sperm finally than even the grains of sand I was talking about, more even than the degrees. Well—am I making the picture for you? Am I connecting the dots? Ben, Ben, Nick the Greek wouldn’t lay a fart against a trillion bucks that you’d ever make it to this planet!”

Given the time, after re-reading Van Gogh’s Room at Arles and writing a couple things on Elkin, I would love to veer off and look at Wallace Markfield (especially To an Early Grave) and Ben Slotky’s An Evening of Romantic Lovemaking, to think about the ways they create and sustain voice. Slotky’s book is also interesting for how it falls into the subset of Dalkey voice-driven novels in which the narrator is trying over and over again to tell a story. Testing material at times, or just incapable of advancing the plot. Which is also related to the subset of Dalkey backlist titles that use repetition as a narrative tool. Which brings us to . . .

The Making of Americans by Gertrude Stein, Foreword by William H. Gass, Introduction by Steven Meyer

The phrase, “as I was saying” is repeated at least 955 times in this book. Literally. No exaggeration.

Which is probably what most people know about The Making of Americans—if they know anything about it at all. That and that it’s hella long. Which it is. The new Essentials edition is 1,022 pages long to be exact. It’s a massive book that, at least in stated intent, is the “history of a family’s progress” and in some ways a history of America as a whole.

It took me almost four full months to proof this book, which also marked the first time I read the book in full, but over this long, drawn-out process, I frequently found myself so absorbed in Stein’s language that I began to write and speak and think like this book. There’s something magnetic about the way she repeats a particular term or phrase over and over, letting it accrue a richness of meaning so that, when it comes up again later, a phrase like “bottom nature” goes unquestioned, functioning as a sort of shorthand, a code for the aspect of being that she’s now trying to articulate. It’s a book that felt like a dream at times, but then would suddenly snap into place and become the most profound, crystal clear articulation of what it means to be human that I’ve ever read.

More and more in his living loving was to him beginning until in his latest living he needed a woman to fill him, later when he was shrunk away from the outside of him he needed a woman with sympathetic diplomatic domineering to, entering into him, to fill him, he was then shrunk away from the outside of him he was not simple in attacking he was not really getting strength from wallowing, loving was more and more to him as a beginning feeling.

When that makes total sense to you, you know you’ve been Stein-pilled.

As I was Saying by Cecilia Konchar Farr & Janie Sisson; Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade

Which is why it’s so great that these two books are also coming out around the same time as the new edition of The Making of Americans.

Farr & Sisson’s book is the very first reading guide for Stein’s most ambitious and, in at least some regards, greatest achievement. This fact should be much more shocking than it is, but still, here we are, exactly 100 years since the novel’s first publication in 1925, and we’re just now getting a guide welcoming new readers into this tome of excess—an excess of language and repetition—and initiating them to the joys and wonders of Stein’s writing. It’s worth taking the months necessary to read these two books alongside one another and fully immerse yourself in this text. The Making of Americans much more contemporary in its articulation of psychology and the human spirit than one might expect. And although the sentence rhythms take a minute to calibrate to, once you start to get her pacing and quirks, it really is a smooth read—it’s just one of those sort of books you just have to give yourself up to.

*

And Wade’s Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife is one of the books I’m most looking forward to. (Scribner never approved my galley request on Edelweiss, so I’m waiting, anxiously, for both this and Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket to arrive on the same day.) Like so many other English majors, I found the Lost Generation of writers (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc.) to be romantic as fuck, and I ate it all up—but always gravitated toward Stein who, in my world, at the time, I connected with Kathy Acker. But outside of The Autobiography of Alice B. Tolkas, I’ve never read a biography of Stein, or at least not one in which she was the primary figure.

If you’re going to give Stein a try—or are on a general Big Book kick—this October might be the perfect time . . . And hopefully I’ll have Farr and Wade on the podcast to talk about their books and Stein’s lasting legacy in the near future to celebrate the centenary and their books.

From here, my personal interest leans toward revisiting Djuna Barnes’s Ladies Almanack for more historical reasons,2 and Dumitru Tsepeneag’s Vain Art of the Fugue, Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, and Danielle Mémoire’s Public Reading Followed by Discussion to look at the different uses of repetition and narrative speed. And speaking of repetition . . .

Chapel Road by Louis Paul Boon, translated from the Flemish by Adrienne Dixon, Introduction by Chad W. Post

I’ve written Boon too many times now . . . In fact, I posted my entire introduction on this Substack a couple months back. Which is about how I came across Boon, a trip I made with John to the Netherlands, and what makes Chapel Road a Dalkey Essential.

A common trope among Dalkey’s most beloved books is a character within the book writing a book. Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds is a novel about a young man writing a novel within which a novel is being written and the characters have to write their way out. It’s a form Gilbert Sorrentino plays with in Mulligan Stew, his novel of poorly written chapters that pays homage to At Swim-Two-Birds while innovating on the trick. Most of Dumitru Tsepeneag’s intricately structured books are about writing the struggles of writing a novel. The Making of Americans is incredibly aware of itself as an attempt to write a novel. Coover’s A Night at the Movies. All of Barth. The number of examples in the back catalogue are too many to list here. Especially when you include not just the books with the narrator explicitly writing a book inside the book, but books that puzzle themselves out as they go.

This sort of play, in which a novel is aware of its construction in progress, dates back to the Greeks, runs through Joyce and Tristram Shandy (the book I’m going to likely fail to convince you is most closely aligned with Chapel Road) and the work of all the authors named above, is, to a lot of people who fall into the orbit of Dalkey Archive’s backlist, incredibly fun and rewarding to encounter in all its iterations from across the globe.

And in 2021, I wrote this post about traveling with John to the Netherlands and discovering Boon.

It must have been so disorienting to the people at the Dutch Foundation for Literature to have a young American show up in their country, poorly dressed (still haven’t figured that one out twenty years later) and desperately seeking information about an author whose name he mispronounced every single time (it doesn’t rhyme with “moon”). An author who didn’t technically write in Dutch and thus wasn’t eligible for funding from the very organization that flew us over, put us up in a swanky hotel, and was thrilled to finally tell someone in America about all the new, living, exciting Dutch authors worthy of discovery. Instead, there I was asking—over and over—about an author who passed away in 1979, was critically respected but maybe not that well-read, and had a reputation for being a bit of a porn connoisseur. (This is pretty much shorthand for the typical Dalkey author, I suppose.)

And since this post is all about excess and repetition, here’s the opening to Chapel Road, which is quoted in both of the pieces above—and now in this one as well:

Chapel Road which is the book about the childhood of ondine, who was born in the year 1800-and-something . . . who fell in love with mr achilles derenancourt, director of the spinning mill ‘the filature’, but who will at the end of the book marry poor oscarke . . . about her brother valeer-traleer, with his monstrous head wobbling through life this way and that . . . and about mr brys who was one of the first socialists without knowing it . . . about her father, vapeur, who wanted to save the world with his godless machine, and about all the things which I can’t quite recall now, but which try to draw a rough sketch of the laborious RISE OF SOCIALISM, and of the decline of the bourgeoisie which got knocked down by two world wars and collapsed. But between and besides this it is also a book set in a much later time, in our own time of today: whereas ondineke lived in the year 1800-and-something, msieu colson of the ministry, johan janssens the journalist, tippetotje the painter, mr pots and professor spothuyzen—and you yourself, boon—live today, in search of the values which really count, in search of something which will check the DECLINE OF SOCIALISM. But . . . heaven help us if it isn’t going to be more than that: it is a pool, a sea, a chaos: it is the book of all that can be heard and seen in chapel road, from the year 1800-and-something until today.

Dalkey’s Flemish literature game is strong. In addition to wanting to re-read Summer in Termuren, the sequel to Chapel Road, I’d love to find the time this fall to re-read Omega Minor by Paul Verhaeghen, and Arriving in Avignon by Daniel Robberechts (a book that came out after I had left, and which I haven’t read). But Boon also makes me want to veer off into the Shklovsky-verse and read Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot.

And if these three Essentials in all their excesses aren’t enough for you, the final book in this batch is maybe the most explosive of them all . . .

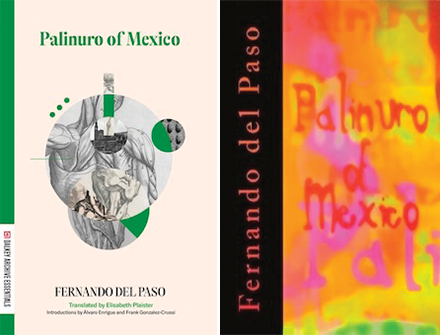

Palinuro of Mexico by Fernando del Paso, translated from the Spanish by Elizabeth Plaister, Introduction by Álvaro Enrique

And here we are, at another celebration of excess, Palinuro of Mexico, a book referenced in the MA thesis I just read, a novel we referred to at Dalkey as the “Mexican Ulysses,” a book filled with lists upon lists, a kaleidoscope of literary forms comprised of a truly overwhelming amount of information and detail, a literal torrent of words, a novel that is both overwhelming and one of the funniest, most enjoyable books coming out this year.

Del Paso was a massive literary figure with a major cult following—in both Spanish and English—who is much overdue for a rediscovery. News from the Empire, the only other book of his translated into English and which was longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award, came out in 2009—sixteen years ago. Palinuro of Mexico was first published by Dalkey in 1996, and has had that same color-drenched cover right up until now.

This is a book for every Pynchon reader, for all the fans of Joyce and Nabokov, for anyone who loves García Marquez and José Donoso, or who loves Big Books that acknowledge that Serious Literature can also be Funny, who are lovers of Rabelais and Letterkenny, of the core improv concept of “yes, and,” and it’s also for anyone who doubts the truth of the maxim, “less is more.”

Lori Feathers of Interabang Books, the Big Book Project, Involutions of the Seashell, and more, is a massive fan of this book, and is already planning to come on the podcast to talk about it and the amazing review she wrote for Southwest Review. (And maybe we’ll have another special guest for that episode . . .)

This is also a book that deserves its own season of the Two Month Review, and makes me want to go back to José Lezama Lima’s Paradiso and Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s Three Trapped Tigers, and, especially, Larva by Julian Ríos, which is most definitely a future essential, and whose House of Ulysses, which is being reissued next summer, is also quite wonderful.

I’m going to end this “preview post” with a final nod to “excess” in the form of this single paragraph from Palinuro of Mexico:

Of the forty-five times that Palinuro appeared in my life, it is this, the first, that I will best remember. The clockwork of winter, accurate to the instant in its whiteness, clung to the first sepia step of the colonial mansion in Holy Sunday Square. You must remember it well, Estefania, because, just as you and I were born in the same room in the same house in the same city, so Palinuro came into the world—that is to say, he came into my world—in the very building, and none other in the whole of Mexico City, where you and I lived and dreamed of each other and, what is more, the room in which Palinuro lived on the fifth floor was the very room and none other in that building, in the whole of Holy Sunday Square and in the entire universe, where you and I, Estefania, tirelessly and amazingly made love, on the bed, on the floor and in space, naked, clothed, awake and half-asleep, to the envy of our friends, of our relatives, and of the Farmers’ Almanac. In the very room where we fought with words and with objects and made up with them. In short, in the very room which we had had made to the measure of our desires and of our memories and to which you would return in the early mornings after your night shifts at the hospital, tired from shaving the pubes of patients going to the operating theatre and of pre-warming bed pans and washing the sores of patients in perpetual coma, and to which I would return after passing through the advertising agencies and other imaginary islands, tired from creating campaigns and advertisements for Canada Dry, slogans for Palmolive, and jingles for Campbell’s Soup and firm in my intention to enroll once again in the School of Medicine and never more forsake it. The concierge walked ahead of me up the stairs where you and I were one night to come across Palinuro crawling on all fours in pursuit of glory, there on the second floor, do you remember? Outside the postman’s door, the concierge explained to me that I was going to share and adorn my room with a rancid medical student and my happiness knew no bounds. A cluster of diverging clover leaves entwined their hesperidia, a sturgeon of ice slid down a thread of silver and loosed its eggs into the air, and that splendid caviar turned into a flying fruit shop. “He always has his record player on that loud, you’ll get used to it,” the concierge said to me, unstinting in her belches. From corner to corner, on the snowflakes carried in the white crows’ beaks, the chipped cups dusted themselves with Nescafé and through the circle of the skylight, lean and earnest, the light scattered over the concierge’s Medusa locks. “And, to make matters worse, he’s only got one record. Perhaps you can persuade him to buy a new one.” And so we reached the fourth floor, do you remember, Estefania? where the drunken doctor lived and his mad lady neighbor and, now and again, you could hear the spores of a gelatinous conversation, and I continued to climb the endless stairs of that old colonial building of red foam, submerged in the darkness of a brew of seaweed, between greenish and opaline, with hints of apple camphor and rotten egg yolks, towards the immense organ of burning wind composed of the glass flasks, test tubes and retorts of the alchemic cathedral belonging to Palinuro, whom I was about to meet, as the concierge told me, around the corner of a cornice or in the drainpipe of shadow which acquired, suddenly, a tempestuous translucency. And so it was; I swear I will never forget it: beneath that light of oily cellophane, in the middle of the room and some way from the window which looked out over the street and the afternoon, was Palinuro, naked from the waist down and from the waist up, prescribing for himself a sit-down bath in an aluminum tub full of vinegar. The pandemonium as we entered was such and so often was that sweetest swaying of Vivaldi’s “Winter” repeated, leaving a creeper of lithe notes hanging in the air, that I had to walk over to the record player and turn it off.

Now maybe I can get myself to finish the Echenoz post I mention every single week . . .

Publishing seasons are an abomination. We have two seasons at Consortium: Fall-Winter and Spring-Summer. One covers seven months, the other five. A lot (most?) big presses and other distributors have three seasons. I assume, but can’t confirm, that those are broken up evenly into four month chunks, but even so, what three seasons are these? Does Smarch come into play? What about the Eastman Kodak Calendar?

Ladies Almanack is a Dalkey Essential coming out in this same “season,” but I want to “preview” it in a different post.

So much to look forward to. Great post.

I think I'm starting a list of "books from Mexico I should read" and I think Palinuro of Mexico is on it. I'm sort of irritated with you for adding to my TBR pile.