Two Authors, One Dissertation

John's dissertation and a couple of Dalkey authors to read.

Quick question—which of the following was the subject of John O’Brien’s doctoral dissertation?

Gilbert Sorrentino: The Sky Changes, but Divorce Is Never-Ending

Flann O’Brien vs. James Joyce: Dueling Irish Word Magicians

The Oulipo and the (Im)Possibilities of Form

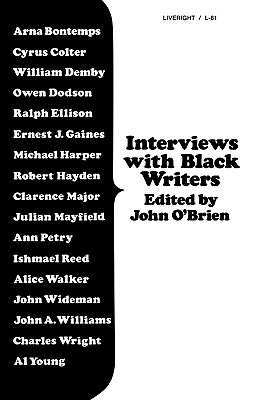

Interviews with Black Writers

Given the Dalkey authors who are most frequently cited—Flann O’Brien, Sorrentino, Queneau, Nicholas Mosley, Gertrude Stein—it might surprise you to know that not only is 4 the correct answer, but it was published by Liveright1 in 1973 and is still in print.

A number of the authors John talked to are still extraordinarily well-known. Writers like Ralph Ellison, Ernest J. Gaines, Ishmael Reed, and Alice Walker. But he also included a number of writers whose works have gone in and out of print and are still ripe for rediscovery: Cyrus Colter, William Demby, Clarence Major, John Wideman, John A. Williams, and Charles Wright to name a half-dozen.

From the introduction:

There exist a number of critical fallacies about black literature which continue to impede the black writer in America. The first, is that the greatest service the black writer renders is not artistic, but political and sociological; that he reflects the mood of black Americans and affords insights to a white audience concerning the elusive thing called the “black experience.” Even the Literary History of the United States, the Bible of literary scholars, cites the tradition of Negro writing as having begun with Claude McKay and Countee Cullen and as being presently continued by “publicists” like Adam Clayton Powell! Not only does this critical approach to black literature limit the writer to certain themes and styles, but it also demands that he concern himself with only that element of the “black experience” which is political and social.

An extension of this first fallacy is the idea that there is a bond of some kind between all black writers, and that it is legitimate and necessary to speak of them as a homogenous group. The deluge of black literature anthologies issued in the 1960s perhaps best demonstrates this critical attitude. Rarely was there any rationale for including writers other than the fact that they were black. [. . .]

Although such groupings may please both white racists and black nationalists, it is strange that professional critics, trained to distinguish between rhetoric and art, should be guilty of such an error. Yet, as John A. Williams points out in his interview, book reviewers consistently, when discussing books by black writers, compare the book before them only to books by other black writers. The danger of such criticism is that in effect it either dismisses every black writer who does not seem to conform to the formula of what the black author should be, or it forces him into a mold, whether or not his work belongs there.

Finally, the black writer is rarely talked about as an artist. Such matters as style, form, structure, symbols, and characterization are usually ignored by critics. Most criticism of black literature is devoted to a discussion of the “message.” This indifference to form has led to the great misunderstanding about themes. Meaning and form are inseparable, and it is only by ignoring form that one can think of black writing as protest literature. Nevertheless, the majority of critics, white and black, liberal and conservative, have yet to begin talking about black literature as literature. Lacking the support of critics, several black writers themselves have spoken out to urge critics to apply the same critical standards and perceptions that are given to their white contemporaries.

I don’t want to speak to how these attitudes have or haven’t changed since the 1970s, but the sentiments John was getting at here—lumping particular writers together, ignoring form for social meaning—are ones that he also applied to “innovative writing” and international literature.

One of the funniest stories John ever told me was about how he got into a lengthy debate with his thesis committee about whether the dissertation he submitted was valid. He argued from the point of view that interviews might be unusual, but given that the book was published, had received critical acclaim, and was truly invaluable at its time for anyone studying black authors, it should be fine.

Turns out the committee was much more concerned about how the book—its size, and more particularly, its margins—didn’t mesh with specifications from the university’s handbook. Because, of course.

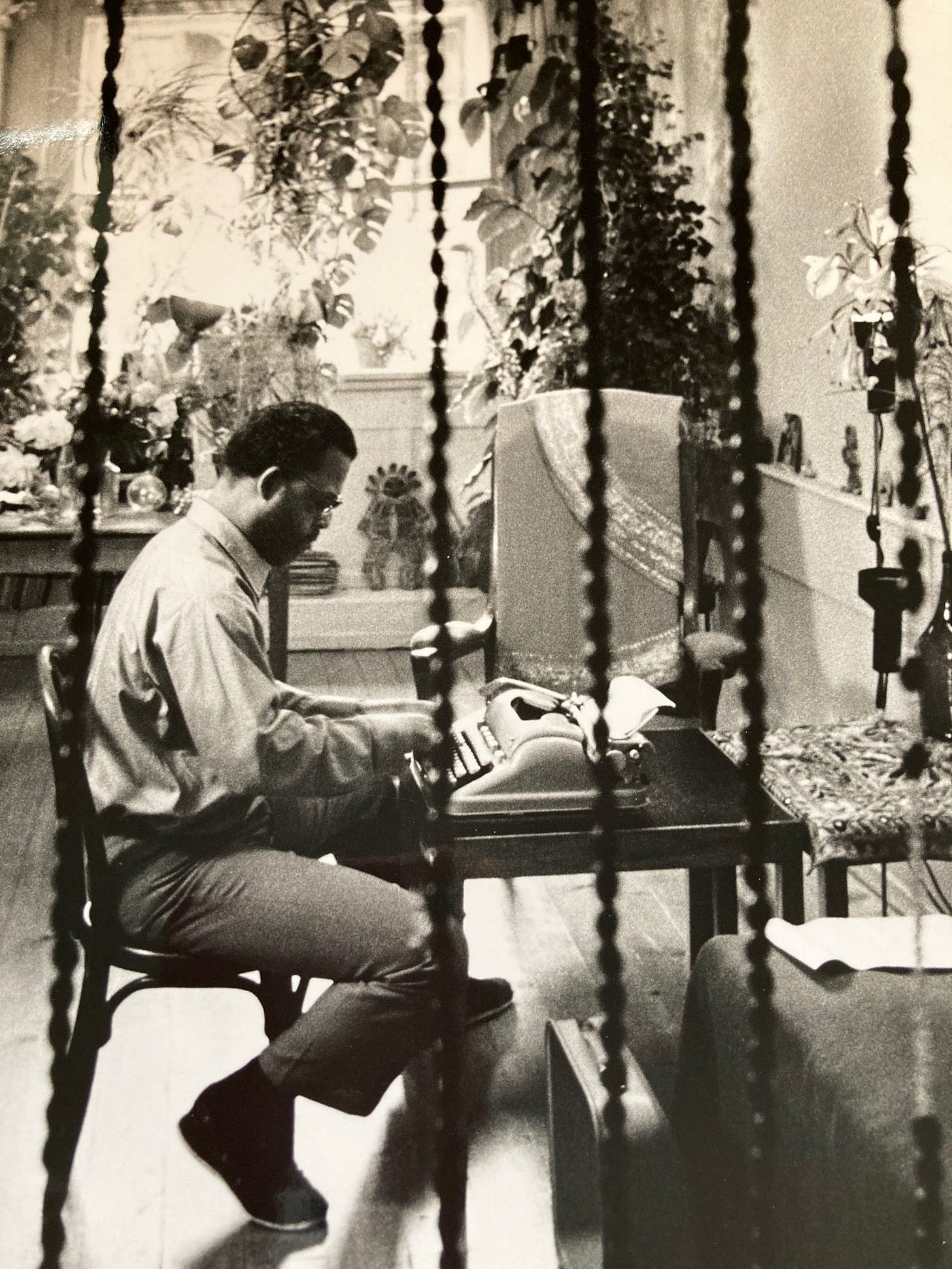

On the subject of interviews:

There are built-in limitations in the interview format. Oftentimes they seem to be without direction in the sense that they lack a central idea or thesis that is stated and developed. Likewise, the interview depends upon spontaneous conversation in which the quality and clarity of expression sometimes suffer. The objections are admittedly valid; but the interview format, because of its flexibility, allows for a breadth that an essay cannot encompass. The subject of each interview is the author himself. There need not be the orderly and logical development of the essay. In this way, many things can be touched upon without the necessity of demonstrating an intimate connection to a central idea. Although it does not have the depth an essay might possess, the interview is free to wander over a landscape composed of whatever seems interesting. There is also something wholly fascinating about what an author has to say about himself and his work. The spontaneity of the form is compensated by careful editing by both the editor and the author. In each case we tried to shape the raw materials in the best way possible without destroying the sense that these are conversations between a critic and writers.2

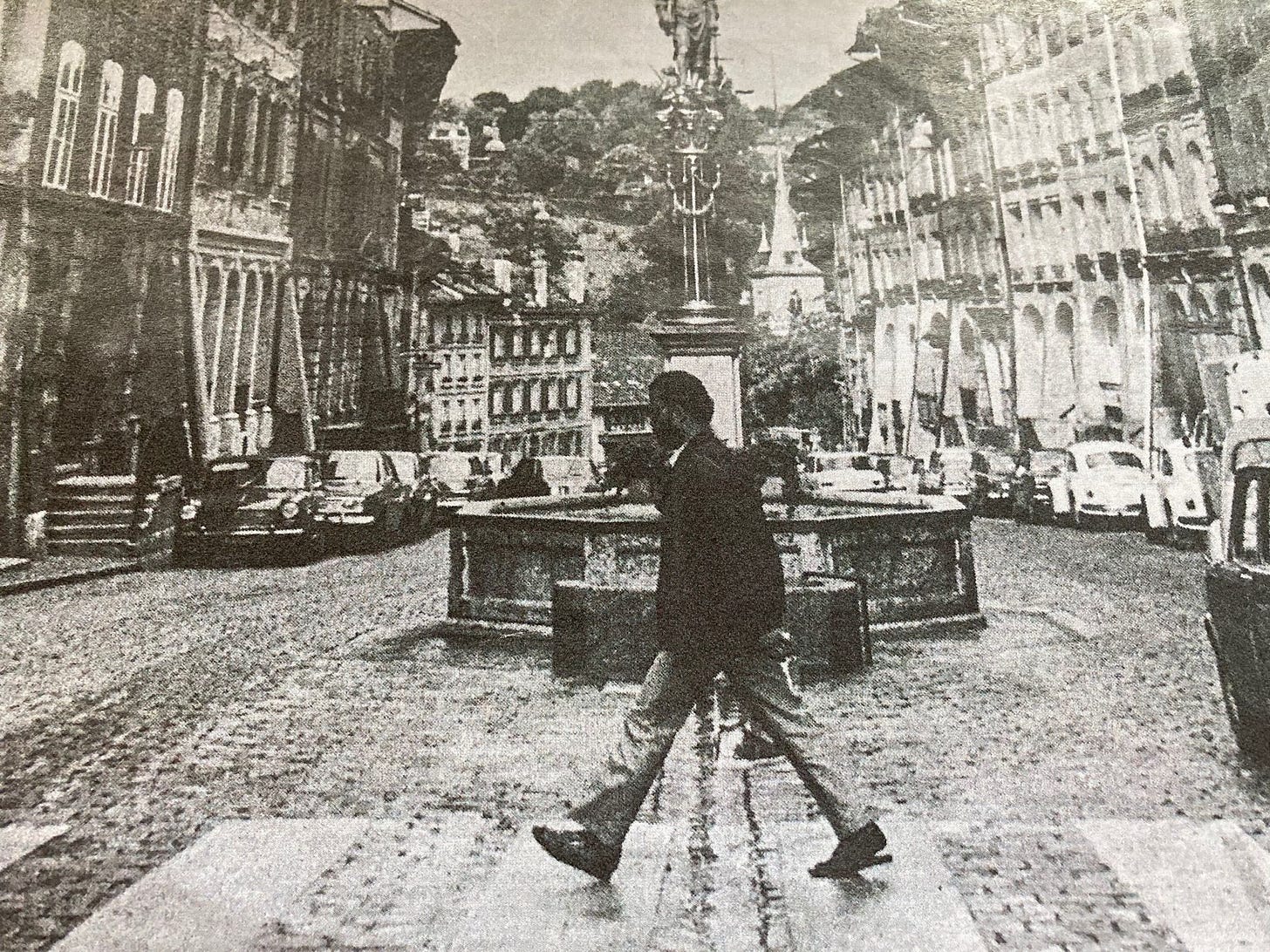

Although he missed the opportunity to establish a Dalkey “series” featuring authors from his book, John did manage to publish a number of interesting books by black writers, most notably Ishmael Reed.

Of Reed’s eleven novels to date (I’m not counting The Fool Who Thought Too Much since it’s an Audible Original and The Terrible Fours, which is forthcoming), Dalkey has reissued or been the original publisher for eight of them. Additionally, John did Ish’s collected plays and, most recently, Why the Black Hole Sings the Blues. (At the same time that Dalkey brought out his daughter Tennessee’s Califia Burning: Poems, 2012-2019.

If you’ve never read Reed, you’re in for a wild, amazing, hilarious trip. Always savage, always honest, always engaged, and always playing with different conventions and forms.

Putting aside Mumbo Jumbo, which should be (is?) required reading, the first Reed I read was Reckless Eyeballing, mainly because Dalkey reissued it right around when I drove from Durham, NC to Normal, IL to interview for a “publishing fellowship.” It’s been twenty-one years (almost exactly, which, gulp), but what I remember is how charged and how completely scathing this book was. Reed takes no prisoners in his examination of American hypocrisy. (A statement that could equally apply to the more recent Juice! about the obsession with O. J. Simpson.) Crass, unforgiving, darkly funny—the same adjectives you could apply to this book could be applied to the aesthetic of Dalkey Archive around that time. Books that didn’t shy away.

Both The Terrible Twos and The Terrible Threes (and forthcoming Terrible Fours) are set in the near future and take aim at Wall Street and politicians. These will never not be timely.

But if I had to choose one Reed book to recommend from the Dalkey list, it would be Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. (Which is at the top of the list to be reprinted with a new cover.) It’s a “HooDoo Western” that opens as such:

Folks. This here is the story of the Loop Garoo Kid. A cowboy so bad he made a working posse of spells phone in sick. A bullwacker so unfeeling he left the print of winged mice on hides of crawling women. A desperado so onery he made the Pope cry and the most powerful of cattlemen shed his head to the Executioner’s swine.

A parody of traditional Westerns, this was Reed’s second novel, and his most recent when John interviewed him. (At the time, Reed was working on Mumbo Jumbo.)

INTERVIEWER: When the children take over the town in Yellow Back they give as their reason that they want to make “their own fictions.” They do not talk about social or political reform. The revolution seems to be taking place in the imagination, not in a political-social environment. Is it a revolution of the imagination that you are working toward in your fiction?

REED: "To create our own fictions" has caused quite a reaction. The book is really artistic guerilla warfare against the Historical Establishment. I think the people we want to aim our questioning toward are those who supply the nation with its mind, tutor its mind, develop and cultivate its mind, and these are the people involved in culture. They are responsible for the national mind and they've done very bad things with their propaganda and racism. Think of all the vehemence and nasty remarks they aimed at the Black Studies programs, somebody like William Buckley, that Christian fanatic, saying that Bach is worth more than all the Black Studies programs in the world. He sees the conflict as being between the barbarians and the Christians. And, you know, I'm glad I'm on the side of the barbarians. So this is what we want: to sabotage history. They won't know whether we're serious or whether we are writing fiction. They made their own fiction, just like we make our own. But they can't tell whether our fictions are the real thing or whether they're merely fictional. Always keep them guessing. That’ll bug them, probably drive them up the walls. What it comes down to is that you let the social realists go after the flatfoots out there on the beat and we’ll go after the Pope and see which action causes a revolution. We are mystical detectives about to make an arrest. There are some things which we are going to solve and that's the reason the historical establishment is so down on us. They sound like mad monks defending the Church and I think that there's an analogy in that these people really feel they have to save the Western Church. To do this they have to hire thugs who call themselves nationalists and revolutionaries to keep us in line, but as fetish-makers we will get through one way or another.

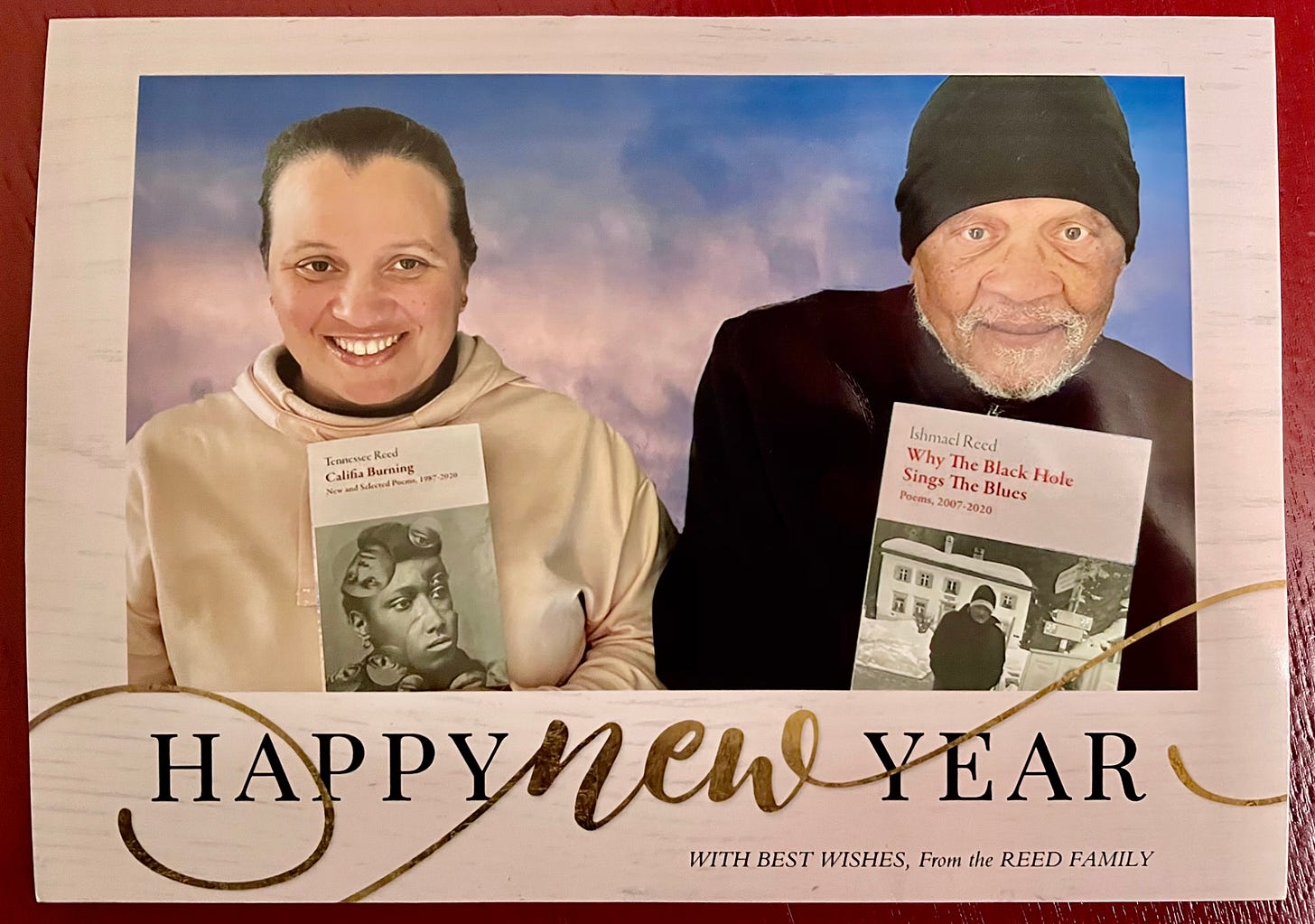

The other book I want to call attention to here isn’t connected to John’s dissertation. It’s The Bern Book by Vincent O. Carter, who was the only black man in Bern, Switzerland when he arrived there in 1953.

This is a book John wanted to reprint for decades. When I was in Normal in the early 2000s, he had me read it, with the intent to reissue. For one reason or another (my brain memories grow dim every day as I march closer to the grave) things never worked out. But twenty months ago, when John and I first got back in touch, I was in no way surprised to see that he was finally reissuing this.

There’s a funny/wild story about the reprinting of this book that I’m not going to tell here (come find me when in-person events are a thing again), but it was the last book published before John passed away, and deserves some special attention for that, if nothing else.

From the Preface by Jesse McCarthy:

The reprinting of Vincent Carter’s The Bern Book: A Record of a Voyage of the Mind for the first time since its publication in 1973 returns to us a text that for almost half a century has survived principally as rumor, a dusty hardback known to certain bibliophiles, or in rare instances as a scholarly footnote. It is one of the “shadow books” of African American literature, a phrase the poet Kevin Young has given to those missing works, both real and imagined, which haunt the tradition like a phantom limb. The reception afforded to uncompromising or eccentric literary works in their own time is rarely a seat at the welcome table. The genius of Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larson had to wait for Alice Walker, Mary Helen Washington and Toni Morrison to create a landscape in which they could be more widely read. There is also no doubt that black writers who experiment with form have always steeply increased the odds of their work disappearing from view. The alleged difficulty in such cases is typically compounded by the suggestion that they are belated (and possibly inauthentic) because of their debt to European modernism. The Joycean encryption of language in William Melvin Kelley’s Dunfords Travels Everywheres was held to be too derivative when it appeared in 1970. Yet Kelley was writing in a very different wake, not Finnegan’s, but his own attempt to sound the linguistic depths produced by the Middle Passage (something quite alien to Joyce’s otherwise omnivorous sensibility). Despite a profusion of powerful and ambitious undertakings—one thinks of Leon Forrest, Gayl Jones and Fran Ross, to name just a few writers at work in the 1970s—the afro-modernist novel continues to dwell at the margins of postwar literary history. In the case of Vincent Carter, however, it must be conceded that one of the principal reasons for his eclipse is simply biographical. In 1953 he decided to go into a self-imposed exile from the United States, but not in the standard fashion. He relocated—not to one of the hubs of literary culture like Paris or London—but to Bern, capital of the Swiss Confederation, a city that to this day the average Helvetic citizen is likely to find terribly provincial. Why Carter decided to stay as the only black resident in that city was the question he would grapple with in his writing and the quandary that would come to define his life. [. . .]

Can a black writer who wishes to be a flâneur melt into the urban crowds of modernity? What distinguishes The Bern Book, but also makes it challenging, is the troubling oscillation between sly humor and genuine melancholy that Carter brings to this question, as he toys with the inversion of relations between provincial and cosmopolitan, primitive and civilized, racial blackness and cultural whiteness. This is reflected in The Bern Book’s parodic relation to the stylistics of classic European travel writing, for example its mock-Victorian chapter headings and its casual dispensation of the sort of digressive generalizations on national character and habits typically associated with the literature of the “Grand Tour.” Carter is tongue-in-cheek when he says that he is in Switzerland to study a “primitive” culture, and yet his ethnographic readings of the inhabitants of Bern inevitably do end up constituting something like a study of their “whiteness.” The suitability of trams as a method of public transit, the precarious social status of girls who work in tearooms, the tendency of the Bernese to overdress, aspects of Swiss politics both domestic and international, and naturally, the many difficulties in trying to secure lodgings in Bern as a black man are all fodder for his Shandyesque ramblings. He is particularly concerned about the Swiss tendency to stifle any creative impulse, which eventually forces artists to leave and go into exile—an implicit and not too subtle rapprochement of a Swiss and American cultural “whiteness” obsessed with order, regulation and commerce, which is inimical to artistic values such as experimentation and creativity.

The urban passageways of Bern effectively become a test site for a black desire for writerly freedom, which Carter’s narrative repeatedly reenacts as a series of disappointments and disruptions, undone by the reassertion of racialization. Subtle moments of repression, of training oneself to ignore and elide slights and navigate whiteness amount to a pointed racial farce that anticipates the form of Claudia Rankine’s vignettes in Citizen (2014) and the strategies of Jordan Peele’s satirical film Get Out (2017). In the end we are left in a situation which has become utterly claustrophobic, teetering on solipsistic madness and apocalyptic visions of Cold War annihilation, a Conradian voyage into the heart of whiteness.

Carter’s writing is fantastic, and I urge you to read this book right now. But rather than quote from the text itself, I’ll leave off here with the most Dalkey-esque aspect of this book—the Table of Contents.

Since I Have Lived in the City of Bern

The Preliminary Question

The Foundation-Shattering Question

Personal Problems Involved in Answering the Question

Now I Philosophize a Little

Why I Did Not Go To Paris

The More Serious Part

A Chapter Which Is Intended to Convey to the Reader the Writer’s Fair-Mindedness

Why I Left Amsterdam

Why I Left Germany

What I Thought As I Walked

Bern

Looking for a Room

Still Looking for a Room and Why

EVERYBODY, Men, Women, Children, Dogs, Cats, and Other Animals, Wild and Domestic, Looked at Me—ALL the Time!

Continuation of the Little Dialogue Interrupted by the Previous Chapter

Some General Changes in My Attitude As a Result of My Preliminary Experiences with the Bernese People

What Happened at the Thunstrasse

The Kirchenfeld

I Leave the Thunstrasse

My New Landlord and Lady

The Public Life

And This Theme Has Another Disquieting Variation

Hearts and Stones: Introduction

Hearts and Stones Continued, or: A Barroom Ballad

The Radio

Through Which “Pressing” I Encountered Ideas Which Were Shocking to My Delicate Sensibility!

And What Did They Have to Say to That?

What Happened in the Weeks That Followed

Paris the Second Time

Why I Was Depressed and Sunk in Misery

The Momentous Decision

How I Left the Kirchenfeld

The New Room

Why I Did Not Work

A Portrait of Irony As a Part-Time Job

The Rendez-vous

The Girls Who Work in the Tearooms

Why the Gentlemen Are Appreciative

Why the Pretty Boys and Girls Did Not Marry

“But Why Do Not More of the Men and Women Who Marry Under Such Unhappy Circumstances Learn to Love Each Other and Make an Adjustment —Together?”

“This Explanation of Yours Cannot Apply to All the Bernesel”

Now I Hear You Telling Me

An Essay on Human Understanding.

What the Day Brings

Topography

Flora and Fauna

The City

The Tendency to Overdress, For Example

The Swiss “Movement”

The Most Important Words in the Swiss Vocabulary

However, I Can’t Repeat This Too Many Times

Switzerland Is Neutral

A Little Sham History of Switzerland, Which Is Very Much to the Point, and Which the Incredulous or the Pedantic May Verify by Reading a Formal History of Switzerland, Which I Have Certainly Never Done, and Will Probably Never Do

An Interesting Effect Which This State of Consciousness Has Upon Women

An Interesting Effect Which This State of Consciousness Has Upon the Concept of Charity

The Way I Used to Give Willis James My Candy When I Was a Little Boy

An Interesting Effect Which This State of Consciousness Has Upon Art

That Most of the Swiss Artists Who Become Famous Leave Switzerland in Order to Do So

But Why Am I Being So Passionate About It

At Whose Performance a Peculiar Thing Happened

A Ten-Line Cadenza

“Abend Dammerung . . .”

I Took Another Look at the City

Why Sorrow Upon Looking Upon the Town from Schos-shalde Hill?

And After the “Negative” Event, a “Positive” Event

And Shortly After That, a “Posi-Negative” Event

And Then the Golden Irony Tugged Once More at My Sleeve

I Took the Tram to Wabem

A Parable

Another Parable

And Then, a “Parti-Valenced” Experience

Before My Eyes the Town Was Constantly Changing into Something Else!

The Scheme

And I Gave My Thoughts to a Few More Mundane Alternatives

. . . I Had Thought of Suggesting

A Message to General Guisan

It Is As Simple As One, Two, Three

This reminds me of Tristram Shandy meets Macedonio Fernandez. (Fernandez’s The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel) being the exact Venn Diagram middle point marking the overlap between Dalkey and Open Letter.)

There’s more to be said—about John’s intentions, his interests, his relationship to form and literature—but this is a good start for future episodes. I’m off to read Ismael Reed and dream of being able to travel.

Next time: We take a look at four European women writers. And I share my attempts at voice acting.

Support Dalkey Archive Press by donating to Deep Vellum, giving me (Chad) a heart or an email, or buying all your books via the Dalkey Bookshop.org store.

Given Horace Liveright’s career as a publisher, which blended a sort of con-man showmanship with great editorial vision—he was the first to publish books by Hemingway, Faulkner, Dorothy Parker, along with The Waste Land and other classics—this is very fitting. John loved to tell the story of the “Hemingway clause” (in which Hemingway got out of his three-book contract with Liveright by submitting The Torrents of Spring, which Liveright rejected for a few reasons, thus missing out on The Sun also Rises and all of Hemingway’s success) and of the launch of Boni & Liveright through a sort of scam by which they convinced the Whitman Chocolate Company to include their edition of Romeo & Juliet in their special chocolate collections before they ever printed anything. (Whitman ordered 15,000 copies of the non-existent books.) Firebrand: The Life of Horace Liveright, The Man Who Changed American Publishing seems to be out of print, but used copies are available.

Secret admission: This view inspired the idea for a book of interviews with translators I was writing until COVID destroyed me.

Thanks for this. It inspired me to finally read Mumbo Jumbo, which I am now enjoying.