French Obsession

I can't come up with a witty, appropriate title, but anyway, this is about Dalkey's French-language fiction and Barbara Wright.

Before getting into the post proper, I have a bit of housekeeping. First off, the Complete List of Dalkey Archive Titles Google Spreadsheet has been updated with information about all books published through March 2026. (Up to 970 unique titles!)

Also, here’s a Google Sheet of all the books from January 2024 through March 2026, which are all available for purchase or preorder on Bookshop. (Also, booksellers, please use this to ensure you have our recent books in your store. There seems to have been some miscommunication with some of our sales reps, so you might have missed some of these. And reviewers: email Nadine at Deep Vellum for review copy requests.) I’ll do my best to keep this up to date as future seasons are announced.

Now, on to the regular post!

French literature is undeniably one of the cornerstones of Dalkey Archive’s catalog. Of the 970 unique titles published by the press, at least 129 or 13.3% have been translated from the French as part of several different “Literature Series.”1 (That link goes to the full list of all that are currently available through Bookshop.org. This is the complete list I came up with so far. Let me know if anything is missing.) According to an interview with John in Context, the first original work of fiction published by the press was Our Share of Time by Yves Navarre—which is translated from the French by Dominic Di Bernardi.

Over the past forty years, the French list has become a repository of amazing writers, with a surprising amount of range. There are the incredibly influential classic authors (Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, Jacques Roubaud, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Roussel, Robert Pinget, Boris Vian, Gustave Flaubert, Michel Butor, etc.), and a slew of contemporary writers who have made a name for themselves in France and abroad (Annie Ernaux, Antoine Volodine, Christine Montalbetti, Jean Echenoz, Lydie Salvayre, Jean-Phillipe Toussaint, Eric Chevillard, Jacques Jouet, Jean Rolin, Olivier Rolin, etc.). And that’s only scratching the surface of what I already know—there are literally dozens of other authors whose work is likely to be really interesting.

More than any other subset of Dalkey’s catalog, the French titles—especially the Oulipian authors—were the books that transformed me into a Dalkey fanatic. Over the course of my involvement with the press, to date, I’ve acquired, edited, marketed, sold, or otherwise worked on 33 different French titles, including all but one of the Lydie Salvayre books (an absolute favorite author of mine), Toussaint’s Television, Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pecuchet (arguably his best book, thanks in part to Mark Polizzotti’s exquisite translation), and the Sarraute reprints. As I’ve probably mentioned in an earlier post, the first jacket copy I ever wrote was for Hortense Is Abducted by Jacques Roubaud. When I started the “Reading the World” project—a collaboration between 10 commercial and independent presses and 150+ booksellers to display 10-20 translated works during World in Translation Month—it was the French Embassy that sponsored and hosted the first big party for booksellers, and who was instrumental in making that program so successful.

Even as John and I started traveling the world, looking to greatly expand Dalkey’s translation initiative to less frequently translated languages and cultures, we never stopped acquiring French books, and every trip I made to New York included a visit to the French Consulate and French Publishers Agency. I had close relationships with several people working in the French Book Office, which helped lead to the publication of As You Were Saying, an anthology edited by Fabrice Rozié and Esther Allen and features American writers in conversation with French ones. Hell, it was thanks to the French and Fabrice Rozié in particular that I was in downtown St. Louis in 2006 when the Cardinals beat the Tigers in 5 and I experienced the greatest night of my Cardinals fandom. Back in the day, we would regularly host events in the Consulate, where Albertine now is, and where the ceremony in which both Harry Mathews and Trevor Wakefield were granted the Chevalier in l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres took place. We were all in on the French.

And even at Open Letter we’ve done a decent number of books translated from the French, all by world-renowned authors: we introduced the English-speaking world to Mathias Énard via Zone and Street of Thieves, reissued Marguerite Duras’s The Sailor from Gibraltar and did two never before translated titles (L’Amour [not to be confused with The Lover or L'Amante Anglaise or Hiroshima Mon Amour] and Abahn, Sabana, David), several books by Antoine Volodine/Lutz Bassmann/Manuela Draeger, and, of course, the works by Swiss-Korean author Elisa Shua Dusapin.2

Point being: French literature is baked into Dalkey’s DNA. Into its aesthetics, in fact, demonstrably in terms of the early covers being modeled after the classic Gallimard look, and in terms of literary approaches (see: Nouveau Roman, French Minimalism).

And personally, French books have definitely been one of the key building blocks of my literary life.

That said, John used to get pissed at “the French” a lot. Always because they wouldn’t financially support Dalkey Archive’s translations at the level he desired—which some other countries did. He was a firm believer that, without Dalkey, none of these books would see the light of day (probably right given the circumstances of that moment) and that the French should pony up to see their high-minded literary works made available throughout the world.3

But the French have a system. One that is sufficiently bureaucratic to be frustrating, yet logical. Once you had the process down (including the weird calculation transforming a translation from X number of words into Y number of pages with Z number of characters on every page), it was pretty easy to apply—and receive—funding for every title. However, that funding ranged from 35%–70%, and was usually in the 50% range.

From John’s stories, at some point in time, there had been more money allocated to literary projects and the percentage of support a book received was much more substantial, but hey, times change. Especially as more and more publishers come into existence bringing out more and more French translations.

Nevertheless, this always irked John, and after getting into some sort of fight with them about funding—of which I don’t know all the specifics, mostly just the consequences—he cancelled some books, jacked up the price on others, and on the copyright page of A Perfect Disharmony by Sébastien Brebel (an author who is new to me), printed this:

Despite its mission to support French literature in translation, and in particular to support the cause and well-being of translators, CNL (Centre national du livre) would not provide support for the translator of this book, and this at a time when there has been a substantial decrease in the number of books being translated into English. Dalkey Archive urges CNL to return to its mission of aiding transaltors.

Classic John O’Brien behavior. For another example, see the back of issue 12 of Context, which in big bold letters says “Way to Go MacArthur!!!!!!!” followed by:

In announcing $21.5 million in new grants to Chicago arts & culture organizations, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation once again snubbed literature as an art form. This is part of MacArthur’s ongoing effort to ensure that Chicago maintain its position in relation to books and literature, not as Second City, but as Eighth City, finishing well behind New York, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Houston, Boston, and Washington D.C.

Or, look at the front page of issue 23 of Context, which includes a banner across the bottom that reads: “ARTS COUNCIL ENGLAND BACKS OFF SUPPORTING TRANSLATIONS: FULL STORY TO FOLLOW IN NEXT ISSUE OF CONTEXT.” (Spoiler: No such story ever appeared.)

This technique definitely doesn’t make friends or influence people, but it is John at his most John.

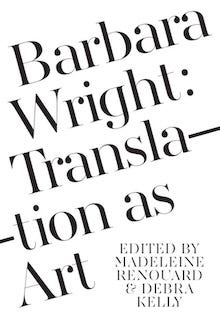

As alluded to above, within Dalkey’s French list, there are several traditions represented, authors famous and obscure, experimental novels and more plotted ones, books I’m already familiar with and ones that have been on my “to read” list for years. And after reading Barbara Wright: Translation as Art, edited by Madeleine Renouard & Debra Kelly, as part of an idea I was toying with about the history of books by and about translators,4 I decided it was time to dive into this section of the Dalkey Archive, explore how some of these books fit together, how the various literary traditions and techniques spin off into other branches of the backlist, and just enjoy some of the most exciting, engrossing, at times playful, at times challenging works of the past century.

To get started in a way that will hopefully be illuminating, I’m going to use four books to more or less guide me: the aforementioned book on Barbara Wright (more about that below), French Fiction Revisited by Leon Roudiez, and what I refer to as the Warren Motte Trilogy of Fables of the Novel, Fiction Now: The French Novel in the Twenty-First Century, and French Fiction Today. In addition to posts about some of the authors and books referenced in these scholarly titles, over the next X number of months, I’ll be posting a number of pieces about French literature from Context and the Review of Contemporary Fiction and elsewhere—a portion of which will be available to subscribers only. Although I have a lot of ideas for this series, this French focus will be supplemented by a lot of digressions, interruptions, podcasts, etc., about non-French books, but for a little bit at least, the French list will serve as a backbone through which to explore the Dalkey catalog and tell some fun stories.

First up is Barbara Wright. Namely, four key authors she translated over the course of her career: Pierre Albert-Birot, Raymond Queneau, Nathalie Sarraute, and Robert Pinget. Pieces specific to each of those authors will be coming over the next few weeks, but let’s start with this book about her and her work.

In addition to an invaluable bibliography of all of Barbara Wright’s “Principal Translations” (91 titles are listed, and I don’t believe this includes all of the radio plays, librettos, and other miscellany she worked on), Barbara Wright: Translation as Art is comprised of four sections: Portraits of Wright, Aspects of Her Literary Translations, a look at her Archives, and a previously unpublished translation of a filmscript by Robert Pinget entitled 15 Rue des Lilas.

There’s a lot that I’m going to be pulling from this book for the individual posts on the four authors mentioned above—ton of interesting scholarship in here, including a number of really detailed pieces that dig into specifics of her translations—so I thought for this post I’d just give a brief overview of Barbara’s life along with some of the wonderful things people said about her.

Barbara Wright—whom I had the great fortune of dining with on a few occasions, and from whom I received one of my favorite keepsakes (more on that in a later post)—was born in 1915 and passed away in 2009 after a long, fruitful life in which she worked with and knew a vast number of the major players in twentieth-century French literature. The aforementioned Pinget and Queneau, obviously, but also Samuel Beckett, Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, their niece Jasia Reichardt and her husband Nick Wadley (more on all of them in the near future), and John Calder, the infamous publisher who had the spirit of a con man and immaculate taste in international literature.

There are so many stories about Calder—I even have a funny one from when I examined his accounting books during Dalkey’s attempt to buy his list—about how he screwed authors out of royalties, held onto rights indefinitely by claiming to sell 1 copy every single royalty period to show that the book was still “in print,” to being on some sort of watchlist due to his strident criticisms of Margaret Thatcher. He was a caricature of a slovenly book person, dedicated more to literature than to fashion, stately in deportment with his cane and three-piece suit with threadbare elbow patches.

Barbara would joke about his financial shenanigans, once explaining that there was no use in taking him to court over non-payments since he could and would always demonstrate just how broke he was from publishing high-modernist books in translation—a state of penury not exclusive to Calder Publications (or whatever name the press was going by at the moment, since he would change it frequently whenever legal complaints arose) in this particular sector of the publishing world. Despite all this, she never really stopped translating for him—he held the rights to some of the best projects after all.

Calder’s tribute to her on her passing is touching and also kind of funny. After saying a few nice things about her work (“In her professional life she was uncompromising. Nothing she undertook could be done in a hurry, nor could there be two ways of translating a sentence or a thought. There was only one way, the right way and she would find it. She was undoubtedly the finest translator of her generation of French to English.”), he presented a poem that includes a somewhat ironic stanza given how long Calder made artists wait for their payments:

She took her time. It must be perfect

Some work was slight: she made it better.

No effort ever was too great.

A publisher must wait and let her

take her time to get it right

before it finally came in sight.

The concept of how meticulous Barbara was in her work is something that’s going to come up again and again over the next few posts. She really did take her time. She immersed herself in the work in a way that’s incredibly admirable and difficult to conceive of in our day and age given the poor pay associated with translation and the never-ending onslaught of life that we all seem to suffering from.

From Madeleine Renouard’s “Working with Barbara Wright” about their Sunday evening get togethers:

Then we would get on with some work until we moved to the kitchen to have supper. We would talk essentially about meaning, which did not exclude other stylistic, psycho- or socio-linguistic issues raised by the text she was working on. The more familiar I was with the text she was translating (Queneau, Sarraute, Pinget), the longer we would discuss her translation. For these writers, language is an issue in itself; its arbitariness is always exhibited (“Rien n’est dit puisqu’on peut toujours le dire autrementi,” writes Pinget).

Over the years it was at this particular moment of the evening that we returned again and again to our fundamental issues and arguments about translating: how to render the ambivalence of a text in another language, how to render this quixotic attempt to track down emotions, thoughts, fleeting impressions. Is there any way for the translator to put into another language what is being said in an avant-garde text about the world? And—when all is said and done—the translator may well ask if indeed anything is being said about society, about the power game between speaking subjects. Being faithful to the text means—for the translator as well as for the critic—being aware of all of these undercurrents. Both Pinget and Sarraute were lawyers; they both knew that language can kill or condone. What may be taken as trivialities in their texts are assertions: the verbal reality exists, it is written or spoken by others but its true meaning remains elusive; be it stilted or witty and amusing, it is a ping-pong game which literature endlessly replays.

The other core tenet of Barbara Wright—as a person and in her translations—is her inventiveness, especially in terms of wordplay. Nick Wadley, who, again, I’ll be writing a lot more about in terms of both his art, Stefan Themerson, and Gaberbocchus Press, hones in on this in his piece, “Barbara, a Portrait Sketch”:

I have read again through all the surviving letters, cards and—latterly—e-mails that she wrote. Her range of signatures, from Barbara to B—via Babar, Bar, Barab, la barbe, and “la barbare (would-be)”—is touched by the light mockery with which she viewed the world and her place within it. One might gather from it, too, the lightness with which she wore successive literary prizes and exotic designations (from Commandeur to Satrape) by which her art of translation was celebrated. One convalescent letter of 2002 is signed “Rorschach blot.” [. . .]

Barbara had a good line in quirky English—both in her oral delivery, broken as it was into a stream of breathless phrases and punctuated by percussive noises, and in the conversational dialect of her letters. Her affection for the colloquial—a key attribute in her armoury as translator—permeated it all. Her correspondence is littered with phrases from popular song lyrics, the Liverpool poets, puns and jingles from the radio; and she used an archaic childish slang that I had grown up with during the war, and which [natch] established common ground between us. She extemporized constantly—ekcetra, ridickerless, probly, hideosity, self-ecstasing. She looked things up in the diksh and posted them in an ombelope. We started openly to share such tastes and cultural flaws through her enthusiastic patronage of and the enjoyment she took in my silly drawings, mostly pictorial/verbal puns, that I started making into postcards in the 1990s.

There’s a lot more to come about Barbara and her works, so I’ll leave off here for now with one final quote from John Updike’s review of Pierrot Mon Ami in the New Yorker:

She has waltzed around the floor with the Master so many times by now that she follows his quirky French as if the steps were in English.

It’s possible that I’m missing a handful, since, at the moment, my database only has the series that a book is part of, not the language it was translated from. (Nor the names of the translators. Summer project!) The 132 titles referenced above and detailed on the accompanying spreadsheet are from the French, Belgian, Romanian, Scholarly, Canadian, Swiss, and Moroccan Literature Series. Not sure where else to look . . .

All in all, over the course of the 25 years of my publishing career, I’ve worked on 48 distinct titles from the French. That’s not bad! This would’ve been an even higher number if I hadn’t gotten pissed over the way the French Publishers Agency handled our offer for Mathias Énard’s Compass, telling New Directions we were passing, even though Open Letter was committed to doing any and all his books, sight unseen. But agents don’t make trustworthy people, and as the “most insufferable man in publishing” (according to a Twitter user), I’m petty and hold grudges, backing away from French literature both in editorial pursuits, and as a reader after that.

I will be running some of John’s pieces about the funding situation for translations in the near future. There’s a value in looking back on these to see the construction of his argument for support and seeing what, if anything, has changed over the past decades.

Basically, I think books about translation fall into three big buckets: 1) biographies of translators, honoring their career and accomplishments, focusing on what they added to literary culture through their work (The Man Between: Michael Henry Heim & A Life in Translation, edited by Esther Allen, Sean Cotter, & Russell Valentino, Chasing Lost Time: The Life of C. K. Scott Moncrieff: Soldier, Spy, and Translator by Jean Findlay, Constance Garnett: A Heroic Life by Richard Garnett), 2) books about the practice of literary translation, focused on how to become a translator and stay alive (Literary Translation: A Practical Guide by Clifford Landers, Performing Without a Stage: The Art of Literary Translation by Robert Wechsler), and 3) translators promoting their theories about the art and craft of translation that tend to use examples from the translator’s work to point to, explore, and clarify larger issues (Sympathy for the Translator by Mark Polizzotti, The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls).

There’s also a fourth bucket of books about translation or international literature as a whole (or fifth or sixth bucket, whatever, every system is incomplete), such as Lawrence Venuti’s work (The Translator’s Invisibility, Contra Instrumentalism: A Translation Polemic) on the theory side of things, David Bellos’s Is That a Fish in Your Ear?: Translation and the Meaning of Everything, which takes a more bird’s-eye view of translation and the flow of literature across languages, and Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States that examines some specific elements of translation, but is mostly about international literature as a whole.

Ooooh. I don't think I have a copy of NEWSPAPER, which is why I went with the one that I had come across, but the Levé one sounds way funnier (and rings a bell).

Bravo to Barbara, Dalkey, Calder, Atlas, and others for their work; for the delivery of great pleasure to me at least.